Alternative Methods of Taxi Entry Management License Caps Price

advertisement

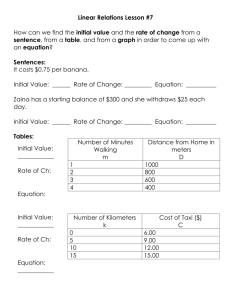

Alternative Methods of Taxi Entry Management: License Caps, Price Rationing, or Performance Standards? 1 Dr. Dan Hara2 Most jurisdictions cap the number of taxicabs permitted to operate. Originally imposed to prevent excessive competitive entry during contractions in the general economy, caps have disadvantages. Regulators need technical insight to set the number of taxis correctly, and political will to adjust that number when demand increases. High prices around the world for taxi permits signal the failure of regulators to meet these challenges. Permits sell for as a high as $1 million USD in New York and $490,000 AUD in Melbourne.3 The implied monopoly means artificially high prices to users, and lost consumer surplus from restricted supply. Low taxi supply also has long-term impacts on public policy to encourage public transit; to accommodate higher disability rates in an aging population; and to manage bar closing and drunk driving in entertainment districts. This paper considers whether there are alternative methods of entry management with fewer disadvantages. Price rationing (the sale or leasing of taxi licenses at a high fee by a public authority) is compared to traditional license caps. Also considered is entry management by monitoring standards of service delivery. Analysis includes impacts on efficiency, government revenues, fairness, and political sustainability. Taxicabs are a heavily regulated industry.4 Standards commonly are set for taxi drivers, taxis, and taxi companies. Price and quantity (meter rates and number of taxis) are also commonly regulated. Regulation of price and quantity goes beyond the regulation of most other service industries. In the case of restaurants, regulators inspect kitchens for health, but do not commonly set menu prices or limit the total number of restaurants. Reasons for regulating taxis to this degree include the inability of customers to adequately assess vehicle and driver quality before entering the vehicle; the efficiency of having a common price contract and sealed device to monitor distance and time charges; and the lack of knowledge of taxi brands (sometimes termed colours) by visitors to a city. This paper focusses on one aspect of taxi regulation: managing entry into the taxi market. Should there be barriers to entry? Is there a valid policy rationale? Are there alternatives to capping the number of taxis that are more efficient, fair to existing stakeholders, and politically sustainable? Five possible regimes for entry limits are reviewed: 1. Open-entry. The default regime in the absence of entry-control. Analysis assumes the choice of entry management regime is made within the usual framework of taxi regulation. This includes 1 This research paper has been commissioned by the Taxicab Inquiry of the Australian state of Victoria. The Taxicab Inquiry was established in 2011 to investigate all aspects of the taxi and hire car industry, and to recommend a set of reforms to the government focused on achieving better outcomes for the travelling public. 2 Hara Associates Incorporated. Ottawa, Canada. www.haraassociates.com/taxi 3 Advertised prices on State of Victoria broker websites as of March 31, 2012. 4 Terminology varies from jurisdiction to jurisdiction, and from continent to continent. In the United Kingdom, a taxi, or hackney carriage, serves the street hail market, while a private vehicle for hire serves the dispatch market. In the United States, the majority of cities license taxis to serve both markets. An exception is New York, where taxis serve the street hail market, while vehicle for hire is a broad term covering the dispatch market and luxury limousines. Unless otherwise noted, this paper uses the term taxi to refer to vehicles providing on-demand service in any of the dispatch market, street hail market, or taxi stands. Page 2 of 23 training, testing, and criminal record checks for drivers, vehicle standards and inspection, and regulated taximeter rates. 2. Quantity regulation of taxis using a cap on taxi numbers: Setting a cap on the total number of taxis permitted (the current dominant model). 3. Quantity regulation of taxis using service standards: This is a variant of quota regulation where the regulator takes advantage of modern technology to monitor service standards directly from taxi company data systems and management reports. For example, the regulator might target 80% of dispatch trips to have meter-on within 15 minutes. When the service standard declines, additional taxi permits are issued to bring service back to desired levels. 4. Entry-price regulation of taxis through permit sales: Regulating the number of taxis indirectly by setting the sale price for taxi permits high enough to deter excess entry. 5. Entry-price regulation of taxis using annual fees: Regulating the number of taxis indirectly by setting a high annual fee (equivalent to the lease price of permit), to deter excess entry. Price-regulation regimes are obvious alternatives to license caps, but have received surprisingly little attention from taxi regulators. Quite a few jurisdictions do auction taxi permits.5 At this time, the City of New York plans to raise $1 billion to $2 billion by auctioning 2,000 new permits for street-hail taxis. However, the auction of licenses takes place within the first regime; the number of permits available is fixed and the auction is a means of distribution that favours the public purse. Price rationing—the alternative to setting a price and letting demand determine the quantity—is different. One purpose of this paper is to explore the price-rationing alternatives to entry control, and to describe the long experience other jurisdictions have had with them. The open-entry regime, above, is not the same as total deregulation. The topic of deregulation has been addressed elsewhere. Notably, Teal and Berglund (1987) document the largely negative results of nine U.S. cities that deregulated taxis in the late 1970s.6 They found that, contrary to the expectations of proponents of deregulation, unregulated meter rates rose rather than fell in most cities; as dispatch taxi firms struggled with reduced market share, the street-hail market was subject to excess entry, and to long taxi queues and high prices. Expected innovations in service did not materialize either. The majority of jurisdictions documented by Teal and Berglund reregulated, including reinstituting caps on the number of taxis permitted. Organization of Paper The origins and rationales for capping taxi numbers are discussed in the next section, followed by analysis of the consequences of poor regulation of caps over time. Alternative entry management regimes are then reviewed. The paper concludes with a summary table comparing advantages and disadvantages of each regime. 5 In the United States, the cities of Boston, Chicago, New York, and San Francisco all auction license plates. In the case of San Francisco, the program is experimental and the maximum value is capped at $250,000. Hara, Dan and Mallory, Charles (2012) Taxicab Regulation in North America. State of Victoria Taxi Inquiry, 2012. 6 Roger F. Teal and Mary Berglund. The impacts of taxicab regulation in the USA. Journal of Transport Economics and Policy .Vol. 21, No. 1 (Jan., 1987), pp. 37-56 Page 3 of 23 1 Capping Taxi Numbers: History and Rationale Capping the number of taxis has been part of taxi regulation for quite a while. In the 1600s both Paris and London licensed and limited the number of hackneys, horse-drawn carriages offering taxi service. Dempsey (1996),7 documents how taxi regulation in North America became widespread in the 1920s, as professional taxicab associations sought to protect themselves from entrants. During the Great Depression of the 1930s masses of unemployed sought to become taxi drivers, creating significant problems and causing many cities to cap the total number of taxis permitted. The following 1933 editorial from the Washington Post illustrates civic reaction to the flood of taxis caused by the great depression: “Cut throat competition in business of this kind always produces chaos. Drivers are working as long as sixteen hours per day, in their desperate attempt to eke out a living. Cabs are allowed to go unrepaired . . . Together with the rise in the accident rate there has been a sharp decline in the financial responsibility of taxicab operators. Too frequently the victims of taxicab accidents must bear the loss because the operator has no resources of his own and no liability insurance. There is no excuse for a city exposing its peoples to such dangers.”8 The relationship between capping taxi numbers and excess entry is generally recognized. The Economist, a news magazine generally favouring open markets, had this to say in reviewing recent regulatory reforms “… On paper, competition should flourish. But low barriers to entry create the risk of having too many drivers on the road. The number of taxi drivers in New York and Washington, DC, shot up between 1930 and 1932, as the unemployed sought work during the Depression. Such surges lead to rules to reduce congestion.”9 The underlying reality is that the taxi business experiences recessions and depressions differently from other industries. In most industries, supply will tend to contract along with demand during a recession.10 In the taxi industry, supply expands during a recession, even as demand for taxis shrinks. The expansion in supply occurs for a number of reasons: 7 Low cost of entry. Entry into the industry requires a vehicle, a driver’s license, and gas. Many newly unemployed already will have these. Absent regulatory barriers, this combination is sufficient to begin to cruise for fares. If the entrant wishes to join a dispatch fleet (or meet regulator vehicle requirements), entry costs are still minor: a meter and a paint job. It is self-employment. A new taxi driver does not need to be hired by a company. If they wish to work the street-hail market, they may begin roaming the streets. If they wish to work the dispatch market, they may retain the services of a dispatch service for a daily or monthly fee. Dempsey, Richard. Taxi Industry Regulation, Deregulation and Reregulation: the Paradox of Market Failure. Transportation Law Journal. Vol24:73, 1996. Pg. 73. 8 Taxicab Chaos. Washington Post, Jan. 25, 1933. Via Dempsey Supra 9 A fare fight. The Economist. Feb. 11, 2012. Pg. 76 10 By definition, this is a recession; industries contract production in response to lower demand, laying off workers in the process. Page 4 of 23 Taxi operators are usually the paying client of taxi companies, rather than employees. Cash transactions combined with low ability to supervise mean that most taxi companies are brokers paid by drivers, rather than employers who pay drivers. New entrants get an immediate share of business. In taxi stands, the first taxi in line gets the fare. In the street-hail market, the closest taxi gets the fare. In the dispatch market, taxi drivers typically book into electronic queues by dispatch zone and take their fares in order. In each case, the new driver gets a basic share, diluting the income share of others.11 As unemployment rises, individuals with very little experience and with vehicles in marginal condition turn to the taxi industry as an accessible short-term solution to unemployment. Where they lack vehicles, they readily can share or lease from others. Even within an otherwise regulated framework, the negative consequences of excess entry during recessions include: Low driver income. With expanding supply and fewer customers, the net income of drivers falls. Short-term decline in service quality. Service quality declines with the increased participation by inexperienced drivers and marginal vehicles. Long-term decline in service quality. Cyclical periods of low income cause experienced drivers to lose their attachment to the industry and find other occupations. Professionalism declines. Fewer drivers know the city well, or know where and when to be to meet customer demand smartly. Further contraction of taxi demand. The increased proportion of poor trip experiences reduces customer demand. Alternative means of transport are sought and people change their lifestyle to be less dependent on taxi service. Administrative burden. If a regulatory regime continues to enforce driver and vehicle standards, the enforcement workload increases at the same time as the ability of each driver and vehicle to support cost-recovery fees diminishes. The increased number of marginal operators also increases enforcement challenges disproportionately to increased taxi numbers. Since there are fewer customers to be served than before the recession, there clearly is a practical incentive for a regulator to limit entry of new taxis—it makes the enforcement problem more tractable while getting rid of unneeded capacity and satisfying the complaints of longer term drivers concerning declining income and excessive competition. In an otherwise well regulated environment, the immediate threats to public safety described in the Washington Post editorial will not manifest themselves. However, a decline in service quality will be felt by customers, and there will be a sharp decrease in income for drivers. Taxi drivers usually collect their income as a residual of revenue minus their gas and fixed expenses. A 20% decline in gross revenue per taxi can mean an even larger decline in net personal income. Income pressure will cause drivers to drive longer hours—exacerbating the excess supply from new entrants. This misery will find representation 11 This does not mean that drivers will earn equal shares. Experienced and skilled drivers will do better, because they will know where and when to be for the best passenger selection, and will have strategies for personal business development using their cellular phones, and for tipping hotel doorkeepers and dispatchers. Page 5 of 23 before the regulator and before elected representatives—resulting in the caps on taxi numbers seen in most jurisdictions today. Entry Limits and Dispatch Markets Some authors have argued that the rationale for entry limits does not apply to the dispatch taxi market. Schaller (2007) presents the case that open entry (i.e. no cap on licenses) in the dispatch market is viable if there are entry controls in the street-hail and taxi stand markets.12 Examples cited by Schaller focus on dispatch companies operating where there are caps placed on airport taxi stands—a key stand market in most cities. Such arguments are beside the point. Open-entry, as opposed to complete deregulation, is viable for both dispatch and street-hail markets so long as the economy is reasonably stable. Learning from failed U.S. experiences in deregulating taxis in the 1970s, the American cities of Minneapolis and Indianapolis removed caps on taxi permits while retaining meter rate regulation and other requirements.13 The city of Washington, D.C. has also been an open entry regulated environment for many decades. The viability of open entry does not mean that the industry is not vulnerable to excess entry during recessions. Rather, excess entry is a known disadvantage of this regime choice. The substantive question is whether the dispatch market is vulnerable to the same excess entry in recessions as the street-hail and taxi stand markets. Certainly, the increased number of drivers and vehicles desiring to enter the taxi market will be a common condition for both the street-hail and dispatch markets. Since most dispatch firms are organized as brokers receiving fees from taxis, there is an immediate incentive to take on as many as can pay. As Schaller acknowledges “In an open-entry system, companies have the incentive to put as many cabs on the street as there are drivers willing to pay lease fees and thus fail to act as a gateway control to entry.” Despite this incentive, the case might be made that taxi companies can chose to limit their intake of taxis, to set high standards, and to market themselves to customers as a quality assured brand. Were this the case, we would expect that companies employing this strategy would come to dominate the market, achieving the customer volume and trip density necessary to sustain an efficient premium dispatch service. In this case, barriers to entry would not be needed since the principal providers would self-regulate. Unfortunately, the evidence indicates that such a strategy is not dominant. In the U.S. deregulation experience documented by Teal and Berglund, the dispatch market suffered in parallel to the street-hail and stand markets. Well-established dispatch companies did tend to pursue a quality strategy, raising prices as well. But such companies also suffered loss of market share from new firms entering the open market, and from drivers abandoning the street-hail market that was rendered unprofitable due to excess entry. The loss of market share is material because it also affects unit costs of operation. As the geographic density of calls and supported trips decline with volume, the average distance between a free taxi and the dispatch address increases. Thus, the rising prices reported for reputable dispatch firms are at least partially absorbed by increased costs. 12 13 Schaller, Bruce. Entry Controls in Taxi Regulation. Transport Policy 14(2007) 490-560. Hara and Mallory (2012). Supra. Page 6 of 23 In a regulated environment with a cap on meter rates, dispatch firms would be even more challenged by excess entry than with the pricing freedom of the deregulation cases reported by Teal and Berglund. The strategy of raising prices to finance preserved quality in the face of lost market share to new dispatch firms may not be available. Finally, modern dispatch and telecommunication technology has greatly lowered the barriers to entry by new dispatch firms since the 1970s. A new taxi firm does not need to acquire its own dispatch centre— it can contract out the service to other firms (a practice common in Australia). From a technical perspective, Global Positioning Systems, computer dispatch, and automated call answering mean that the dispatch service need not be in the same city or even country. Lower barriers to entry mean that excess supply of taxis can find its way into the dispatch market more quickly through new taxi companies. In short, excess entry of new taxis during a recession is a rising tide that lifts boats in both the street-hail and dispatch markets. Barriers to entry at the firm level are also low, so that requiring entry at the firm level, rather than at the individual taxi level, is ineffective in deterring excess entry. Driver Sensitivity to Oversupply One reason the industry is sensitive to over-supply issues is that, even in good times, over-supply already exists as a feature of the system. In a well-functioning system, we expect a taxi to be present at a taxi stand when a customer arrives. The intention is that taxis wait for customers, rather than customers wait for taxis. Similarly, we expect a dispatch taxi to be available when a customer calls (except perhaps bar closing hour or the Friday before Christmas). A wise regulator will set meter rates higher than the market clearing level to ensure that there is excess supply to cover average daily peaks plus random variations in taxi demand. This tendency, combined with off-peak periods, means a taxi driver’s life is often one of waiting, queuing either electronically or at a taxi stand. This creates a large overhead cost of dead time, and a keen sensitivity to minimizing that time as a key feature of being a successful cab. Congestion Rationale Other rationales for entry limits include externalities for pollution and congestion. Since taxis and public transit together form a substitute package for private vehicle ownership, it is difficult to accept the significance of pollution arguments. However, the congestion argument has merits in cities with highdensity downtown cores. New York City is a good example. A glance to the street below from a tall Manhattan building reveals that a high proportion of the vehicles at stoplights are New York yellow cabs. An increase in the number of these vehicles would contribute materially to downtown congestion. New York famously limits the number of street-hail yellow taxis through its medallion system, while simultaneously administering an open-entry market in dispatch taxis. It is the medallions of these yellow taxis that have been auctioned for up to $ 1 million USD. Page 7 of 23 Impact of Lagged Adjustment of Taxicab Permit Caps to Growth in Taxi Demand A risk of capped numbers of taxis is that the regulator often fails to increase the number of taxis to accommodate growth in taxi demand. The negative impacts can be shown in the lease market for taxi permits. In year one, below, the regulator sets a cap of Q1 on the number of taxis. Initially the cap is set at a reasonable level to meet demand while deterring excess entry. Because the permits are limited, individual drivers and others are willing to pay a small price (L1) for leasing. The orange square represents the revenues to permit holders, which ultimately are paid by passengers. The green triangle represents the implied consumer surplus, the value that consumers place on taxi service over and above the amount they pay. In year five, demand has expanded to D5 but the regulator has left taxis at Q1. The increased demand for the fixed supply means taxis are very busy and the lease price is bid up to L5. Revenue to permit holders (the orange box) expands at passengers’ expense. In addition to this transfer from passengers, there is the lost value of suppressed taxi service. Had the regulator adjusted the number of permits proportionate to demand (Q 5), the lease price would have remained at L1. The value of suppressed taxi rides is the blue area, termed the deadweight loss. $ Lease Taxicab Permit $ Lease Taxicab Permit Year One L5 Passenger Surplus L1 Year Five Passenger Surplus . (Inflated Lease Price) . Producer DW Loss D1 Producer Q1 D1 Quantity of Taxicabs Q1 D5 Q5 Quantity of Taxicabs Box 1 2 High Permit Values: The Consequences of Poor Management of License Caps High Permit Values & Regulatory Capture Despite its valid policy origins, capping taxi numbers has a poor reputation. As cities grow, the cap is rarely increased fast enough to keep pace with demand. The limited taxis become busier and more profitable, creating a market value for the rights to the vehicle permit itself (termed plate, medallion, license, or roof light depending on the jurisdiction). While each taxi may be busier and more efficient in the technical sense, this is not a social gain. Either customers must wait longer for these busy taxis or, the regulator must let meter rates rise to reduce demand to available capacity. In either case, the Page 8 of 23 market for taxi services is constrained below the wealth maximizing level for the jurisdiction, and customers end up with poorer or more expensive service. Net losses from lagged adjustment of taxi numbers is illustrated in Box 1, using a supply/demand diagram.14 Over time, it is typical for taxi permit values to greatly exceed what would be necessary to deter excess entry into the taxi business by the unemployed. Taxi permits in Sydney and Melbourne reportedly trade at over $300,000 AUD, and $500,000 AUD respectively.15 A sampling of North American permit values ranges from $USD 20,000 for Houston to $USD 1,000,000 for an unrestricted yellow cab in New York (Table 1). In addition to indicating that passengers are paying too much for taxi fares, high permit values are a visible signal of deeper waste. As with any monopoly, constrained output means the loss of consumer surplus—the difference between the value consumers would have placed on the forgone output and the cost of production. The shared experience of high permit values suggests that capped license regimes are especially vulnerable to regulatory capture. Capture is said to occur when the regulator begins to see the world from the point of view of the regulated industry, and starts to serve the industry’s interest rather than the shared interest of customers, industry, and the general public. The taxi industry may be especially vulnerable to capture since the vested interest of permit holders is strong, whereas it is rare for individual taxi passengers to feel strongly enough to appear at regulatory hearings. In a 2007 report, the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) concluded: Restrictions on entry to the taxi industry constitute an unjustified restriction on competition. Regulatory capture frequently means that these restrictions lead to large transfers from consumers to producers, economic distortions, and associated deadweight losses. 16 This concern led to the inclusion of taxi industry liberalization in the 2011 reorganization measures imposed on Greece by the European Union. The measures were adopted, despite street blockades by protesting taxi drivers. Economic and Social Losses Outside the Taxi Industry Passenger transportation is required by most human endeavours. When taxis are not conveniently available people must, in the short run, choose other transportation or give up on the activity. In the long run, general availability of taxis affects the decision of whether or not to own a personal vehicle. The majority of people in developed nations will own a private vehicle at some point in their lives, but the age at which to start and when to end, is influenced by the alternatives available. In this sense, public transit and taxis are complementary goods—a package of services that is the alternative to private transportation. When taxi supply is unreasonably restricted, the resulting short run and long run decisions by individuals will have economic and social impacts beyond the industry itself. Areas of particular concern include: 14 For simplicity, the Marshallian concept of net surplus is illustrated. Empirical application of diagrams in this paper should consider the appropriate income-compensated demand curve. 15 OECD. Policy Roundtables; Taxi Services: Competition and Regulation. 2007. 16 Ibid. Pg. 7 Page 9 of 23 Table 1: Examples of Taxi Permit Values in the United States and Canada* Jurisdiction Boston, U.S. Chicago, U.S. Edmonton, Canada Houston, U.S. Mississauga, Canada Montreal, Canada New York, U.S. Approximate Number of Taxis 1,825 6,900 1,220 2,270 515 Method of Managing Entry / Licensing Regime Fixed cap Fixed cap Fixed cap Formula. Average of population growth and airport taxi trips. Formula. Weighted average of business indicators. Fixed cap $650,000 (owner-driver) $1M (company) 35,350 Dispatch and prearranged only. Not limited Not applicable Regina, Canada 125 (excluding seasonal) Formula. Per capita, but not in use. Fixed cap 1,585 Fixed cap Toronto, Canada Winnipeg, Canada Vancouver, Canada. $180,000 to $200,000 13,237 Street-hail taxis 1,166 Seattle, U.S. $20,000 to $40,000 4,595 Ottawa, Canada San Francisco, U.S. If Transferable, Market Value of Taxi Permit ($USD or $CAD) $400,000 $275,000-$300,000 $100,000 850 Taxis 260 Dispatch only 1400 (owner-driver) 3,552 (unrestricted) 501 589 $250,000 $150,000 to $180,000 $250,000 (administered maximum) Fixed Cap $113,000 Fixed cap No longer issued Fixed cap Fixed cap No $160,000 $400,000 $400,000 to $500,000 *Various years 2010 to 2012. Sources: Hara, Dan and Mallory, Charles. Taxicab Regulation In North America. State of Victoria Taxi Inquiry, 2012. Hara Associates. Taxi Supply Demand Ratio for Calgary: Phase I. City of Calgary. 2010. Reduced public transit passenger volumes. Cities commonly promote increased use of public transit over private vehicles. In addition to the economies of scale available in public transit, there is the desire to reduce traffic congestion, associated infrastructure expense to handle peak-load traffic, pollution, and greenhouse gas emissions. Because taxis are a complementary good, a lack of availability of taxis will mean less use of public transit. In addition to long run impact on vehicle ownership, the willingness of vehicle owners to commute by bus is partly dependent on being able to get a taxi quickly when needed (called to the school for kids, medical appointment, etc.). Accommodating growing numbers of persons with disabilities in an aging population. One of the groups most affected by taxi shortages is people with disabilities, both those requiring Page 10 of 23 wheel chair accessible transit, and those with more general transportation disabilities (e.g. limited walking distances). While public transit systems may provide special services for this population, budgetary constraints often require passengers to book days in advance, and to allow large windows of time for scheduled arrival of multi-passenger vehicles. On-demand taxi service is important alternative for this group. As developed nations face an aging population, the number of those with disabilities also increases, thereby increasing demand for both regular and wheelchair accessible taxis. Taxi shortages become an important constraint for this group, exacerbated by the appetite by public transit authorities for hiring taxis as a cost-effective means of providing regular service to persons with disabilities, which in turn removes vehicles from the on-demand market. As the population of persons with disabilities grows, this group is also finding greater political voice. Reviving downtown cores and reducing driving under the influence of alcohol. Over the past decades, sentiment has grown against driving under the influence of alcohol. More people desire to take taxis for an evening out, whether it is to a bar or just to dinner. Taxi shortages are an important constraint. Witnessing bar closing in a modern metropolis, one watches crowds of patrons exit establishments and melt away into parking lots—a clear and unfortunate result of a shortage of taxis. In addition to these crowds, there are those who chose to stay home, or visit establishments closer to home. The latter have an impact on another urban policy—the revival of downtown cores. Cities often rely on entertainment districts to sustain or revive their downtown cores. If patrons are expected to make the trip from outside the core to the downtown nightlife, taxi availability is an important strategic requirement. How large are the losses? Price Elasticity Estimates How much lost taxi business volume is represented by the high permit values we observe? This question determines whether the issue is minor, or involves major loses of welfare in the dimensions discussed above. If the regulator were to remove the cap on taxi numbers, while continuing to provide a framework of meter rates and quality standards, would the increase in taxi usage be 10%, 20%, or more than 100%? One approach to estimating the degree of suppressed taxi demand requires just the following information: Gross revenue per taxi. Lease rate paid for permit rights. Where the regulator allows taxi permits to be traded and leased, some permit holders will choose to lease the permit to others rather than use or sell them. There will be a lease market where such permit holders lease to drivers who have vehicle, equipment, and dispatch service, but require one of the scarce permits to operate legally. Where allowed, this is a common industry practice, and there will be a prevailing price for the monthly lease of a taxi permit, separate from the lease of a vehicle, or the fees paid to a taxi company for dispatch service. This income stream is what supports the market value of the permit itself. In Melbourne, as of March 2012, taxi permit leases are advertised publicly for between $2,900 and $2,950 per month, while the actual taxi permit (termed plate) is advertised for as high as $490,000. In Sydney, lease rates are reported at annual rate of $29,000, with unrestricted plate values in the neighbourhood of $450,000. Since this lease rate is for the Page 11 of 23 license, rather than for any physical input required to provide taxi service, the lease payment is also a measure of the monopoly profit being taken out of the system due to the cap on taxi licenses.17 The widespread existence of lease rates on permits can be an embarrassment to regulators. Many forbid explicit leasing, in which case the permit may be bundled with the lease of the vehicle, but still be present implicitly. Many U.S. cities go the additional step of trying to regulate lease rates (inclusive of the vehicle) in an attempt to improve driver incomes. Price sensitivity of demand. Price sensitivity is normally expressed in proportionate terms as price elasticity, the percentage change in quantity from a 1% change in price. If price elasticity is minus one, then a 10% drop in taxi fares would produce a 10% increase in taxi use. If price elasticity is minus five, then a 10% drop in taxi fares will produce a 50% increase in taxi use. Using this method, the percentage of suppressed taxi demand may be expressed as: %Suppressed Demand = - (%Taxi Fare Inflated above Cost) × (Price Elasticity of Taxi Demand) = - ($Permit Lease/$Total Revenue) × (Price Elasticity of Taxi Demand) Consider a practical example.18 The hypothetical city of Midville is busy enough that taxis typically are double shifted. The regulator has long ago capped the number of taxis, and allows taxi permits to be transferred or leased independent of the vehicle. Over time, the value of permits has climbed to $120,000. The monthly lease rate for a permit alone is $1,000, or $12,000 per year.19 The average taxi makes 35 trips over both shifts, at an average fare of $14 per trip including tip. Allowing for downtime, the taxi operates 310 days per year, for gross annual revenue of approximately $152,000. The $12,000/year lease payments represents 8% of the gross revenue. Thus, we may say that for Midville, the actual costs of taxi operation, including the return paid to drivers, is 8% less than the meter rate being charged, including allowance for tipping. This suggests that meter rates could be 8% lower in the absence of the need to reduce demand to match the cap on available taxis. If the price elasticity of taxi demand is minus two—an average value for price elasticities—then an 8% drop in taxi fares would produce a 16% increase in taxi business volume. For hypothetical Midville, this is the suppressed taxi demand. Estimates of the price elasticity of demand for taxis are consistently around unity (-1.0), rather than the value of minus two in our example. Teal and Berglund (1987) surveyed taxi demand elasticity estimates and reported an average value of between -1.0 and -0.8.20 In a cross-sectional estimate derived from 17 More precisely, the lease rate will be bid up by drivers until the price leaves them with a net income equivalent to their next best employment opportunity. Thus the lease rate will be equal to gross-revenue minus the costs of operation minus the opportunity cost of a competitive alternative wage for taxi drivers. By definition, this is the excess profit above normal rates of return being earned as monopoly profit in the taxi industry. 18 The example is a composite consistent with confidential financial information collected for a number of cities. 19 This implies a 10% annual rate of return on the lease. The relationship between revenues and lease rates is governed by the perceived risk of regime change (such as deregulation), and the usual factors governing the market value of any security. The latter includes expected future growth in lease rates, and the covariance of lease rates with the general market for securities (often termed market risk or beta coefficient). Because the taxi industry is highly vulnerable to recessions, the market risk is high. The high market risk combined with the risk of regime change typically means the expected rate of return via lease payments is significantly higher for government bonds or other secure fixed instruments. 20 Supra. Page 50. Page 12 of 23 Canadian cities, Hara (1990)21 found a price elasticity of demand of -1.1. Unity was also estimated by Teal and Mackey (1992) using data from four cities in the U.K.2223 With price elasticity at unity, the volume of suppressed taxi demand and associated welfare losses is proportionate to the percentage of total taxi revenue accounted for by lease fees paid for taxi permits. The portion of revenues going to lease fees will vary from jurisdiction to jurisdiction. Lease rates tend to be higher in more urbanized jurisdictions; however, revenues per taxi also tend to be higher. In general, the high levels of observed prices for taxi permits imply high lease rates, and suggest the size of suppressed demand is nontrivial. Suppressed Taxi Demand May be Larger in the Long Run Other data suggests that suppressed taxi demand in capped regimes may be significantly larger than indicated by price-elasticity estimates. Price alone does not capture the full impact of supply restrictions on taxi demand. Poor service and long wait times can also be a deterrent to taxi use. We may also expect that the impacts of taxi availability on vehicle ownership decisions, and decisions on where and how to commute, may take some time to reveal themselves. An extreme example of suppressed demand is seen in Ireland’s 2010 conversion of Irish taxis to open entry. As a result of a court decision, caps on the issue of taxi licenses were removed and taxi numbers more than tripled within a few years.24 Prior to deregulation, Irish taxi permits traded for £90,000, a substantial sum but not one that would in itself indicate such a high suppressed demand. In Ireland’s case, the issue may also have been substantial wait times during peak periods prior to deregulation.25 Similarly, New Zealand experienced a doubling of taxis overall, and a tripling in its metropolitan areas, following removal of license caps in 1989.26 Another approach to assessing suppressed taxi demand is to compare per capita taxi numbers between cities. Vehicle ownership is a life-cycle decision that is seldom reversed once taken, so that it may take generations for the population to fully adapt to widespread taxi availability. Relaxed supply conditions also affect the ability of the industry to meet peak-load conditions. In the case of full-open entry, parttime taxis become more feasible. Thus, the potential market for taxis may be seen only in cities that have had caps removed the longest. Figure 1, shows per capita taxis reproduced from a survey of U.S. and Canadian jurisdictions.27 Those in orange have no license caps. Indianapolis removed caps in 1994, and Minneapolis removed caps in stages, between 2006 and 2011. Phoenix is a slightly different case. It is one of the U.S. cities that 21 Hara, Dan. Evaluation of Taxi and Limousine Service Demand and Economic Model for Rate Structure. Hickling Corporation. 1990, for the Regional Municipality of Ottawa-Carleton, Canada. 22 Toner, J.P. and P.J. Mackie. “The economics of taxicab regulation: a welfare assessment”, paper presented to the Sixth World Conference on Transport Research, Lyon, 1992. 23 It should be noted that price elasticity of unity is also the point on a demand curve at which total revenue from consumers is maximized. The common observation of price elasticities of unity may speak more to regulatory capture than to the price sensitivity of taxi demand across the entire range of feasible prices. 24 OECD (2007). Supra 25 Daily, Jennifer. Taxi Deregulation Three Years On. Student Economic Review, Vol. 18. 2004 26 OECD (2007). Supra 27 Hara and Mallory (2012). Supra. Page 13 of 23 experimented with full deregulation, and has remained deregulated since 1982. In addition to removing caps, most other forms of regulation were removed. The State of Arizona, which regulates Phoenix, only recently reinstated required criminal record checks for drivers. Most obvious in Figure 1 is the much larger per capita taxi use in cities that have longstanding open entry regimes. New York, although famed for its license caps in the street-hail market, has open entry in the dispatch market. Combining taxis in both market segments yields a per capita taxi use triple many other cities. New York’s high density development in Manhattan (with correspondingly high parking rates and low vehicle ownership) might be argued to be exceptional. However, Washington, D.C. lacks New York’s density but is a longstanding open-entry city in both the dispatch and street-hail markets. Washington’s high taxis per capita occurs despite vigorous competition from surrounding jurisdictions for cross-border taxi commuting by federal employees. 3 Alternative Regime: Regulation of Taxi Numbers through Service Standards An alternative to periodic revision of taxi caps is adoption of an objective rule linked directly to a measure of the adequacy of taxi supply. With the ubiquity of computer dispatch systems, such measures are now possible. Computer dispatch systems are an essential feature of modern taxi companies. Through global positioning systems, a company is able to know each vehicle’s location and whether its meter is on, thereby permitting efficient dispatch to the closest unassigned vehicle. The systems also give each driver information on where the system is busiest so that they can position themselves to receive calls. The result is a fascinating amalgam of computer efficiency coupled with the intelligence of experienced drivers—a system that learns and adapts to a city’s needs. Computerized dispatch also provides tools for taxi companies to manage their fleets. Calls in trouble can be flagged immediately for supervisor Page 14 of 23 attention, and computer records can be used to generate management reports summarizing performance in a number of dimensions, or recalling records of individual trips. With all this potential, it is natural to ask how the taxi regulator should use the information to meet its obligations. For example, it is now feasible to measure service quality in terms of average response time to dispatched calls. In the old paper- and radio-based systems, response time was largely a matter of conjecture. To monitor response times, the regulator’s inspection staff had to make sample calls for taxis in sufficient quantity to be statistically significant. Few jurisdictions undertook this expense. Now, the response time of each dispatched call is knowable. The time from the assignment of the call to when the meter is turned on is easily measured. Alternatively, one can measure from time of dispatch to arrival at the front door (as reported by GPS). To use this capability, the regulator might set a standard that 90% of dispatch calls should arrive at the customers’ door within 15 minutes. When industry performance falls below this mark, more permits would be issued until the service target is restored. Separate monitoring could be conducted to ensure that standards were met for wheelchair accessible taxis. A target for telephone service, in terms of time to answer and dropped calls, might also be established. For the street-hail market, the performance indicator might be the percentage of time a meter is on. When average meter-on time exceeds a threshold typical for a city, the implication is that capacity is strained and customers are finding it difficult to hail a taxi or find one at a taxi stand. More permits would be released until the meter utilization rate fell to a level indicative of sufficient supply. Table 2 provides a sample menu of possible monitoring items adapted from a technological study undertaken for the City of Calgary, Canada. It includes estimated reporting costs to companies where the capacity was not already present (costs in $CAD, 2010). Telephone response time monitoring costs depend on the capabilities of current switches. Ironically, because many new telephone switches are built to be inexpensive, they lack features that were standard on older systems. Although much of this data is generated routinely by companies for their own purposes, few regulators appear to collect it on a regular basis. A survey of large Canadian and selected U.S. cities from the same 2010 work found that only one collected service quality and performance information regularly. Among the conditions of its taxi franchise system, Los Angeles monitors the percentage of telephone calls not answered within two minutes, and trips not served within 15 minutes. It has been doing this for more than twenty years. Most regulators reported no regular data collection, but work with the industry on ad hoc needs for reports and analysis. Where empowering legislation for data collection existed, it was often not exercised. New Trends in Data Collection The long-standing Los Angeles example indicates that political will rather than technological capacity that has limited the application of performance monitoring regimes. However, there is a new trend in taxi technology that offers an opportunity for regulators to improve reporting. Boston and New York have led the way in North America in introducing a higher technology experience for passengers. Page 15 of 23 Table 2: Possible Performance Standards for Managing Taxi Numbers and Service Quality Regulator’s Monitoring Objective Metric Example Report Items Trip volume Monthly Number of Trips: Total trips Trips dispatched Trips hailed Monthly % of trips from entering system to meter-on: % 4:59 minutes or less % 5:00 to 9:59 minutes % 10:00 to 14:59 minutes % 15:00 to 19:59 minutes % 20:00 + minutes Average time to answer. % of calls exceeding 2 minutes to answer Occurrences and duration of ring busy Average % of time meter is on for active taxis. For preselected weekend each month (Thurs.0:00 am to Sunday 24:00) Hourly count: # Vehicles on duty # Vehicles booked into dispatch zone. # Vehicles meter-on Hourly, same format as above for preselected weekend. Dispatch response time Adequacy of Total Supply to Meet Demand & Service Quality Telephone response time % of meter-on taxi time. Vehicle counts Adequacy of Peak Time Supply & Service Quality Dispatch response time Availability by dispatch zone Taxis and/or customers waiting in dispatch queue by dispatch zone. Telephone response time Hourly, same format as above for preselected weekend Cost Implications for Companies with Modern Dispatch System ($CAD)* Minor. Monthly trip volumes part of current management information reports. Minor. Part of current management information reports. Medium ($10K to $20K) to major ($200K $500K) in short run. Minor in long run, if incorporated internet protocol systems. Worst case– requires replacement of telephone switch and system. Minor to medium ($10K to $20K). Medium ($10K to $20K). Usually part of live system reports available on screen, but may require, not be retained by system. . Regular reporting would call for programming timed data capture. Medium ($10K to $20K). Standard reports may only provide daily averages. Regular reporting would require programming a new management report Medium ($10K to $20K). Snapshots are usually generated live to be visible to taxi drivers. Retention may require a programming a new management report. In addition, taxi companies do not use the same dispatch zone structure. Now: Medium to Major now ($10K to $500K) Later: Minor. See above for monthly telephone response time. * Source: Hara Associates. Taxi Supply Demand Ratio for the City of Calgary; Phase II Measurable Service Standards. City of Calgary 2010. **Cost estimates are indicative only. Using a monitor to display the taxi’s real-time progress on a city map, to run advertisements, and provide information, as well as enabling passengers to swipe their own credit card, has revolutionized the backseat experience. Regulators in both cities also now require close to real-time reporting of data on each taxi trip. This information can be used for something as simple as locating a taxi with lost items, to monitoring service quality and geographic coverage. A portion of the costs of these new systems is recovered from advertising. Full electronic reporting of vehicle trips also enables other licensing innovations, such as restricted licenses to serve specified areas or times of day. Page 16 of 23 Advantages and Disadvantages of a Performance Monitoring Regime A performance monitoring rule is a different conceptual approach than caps on permits but, in implementation, it is a variation of permit caps. The regulator responds to poor service data by expanding the cap. In this, it shares the weakness of license caps in that regular application requires political will in an area noteworthy for regulatory capture. The advantage is that it ties the regulator to an objective rule that is directly linked to the adequacy of supply in the taxi industry. In contrast, rules like per capita taxi ratios often are not implemented, even when required by law, because they require hearings to determine if industry conditions truly justify increasing (or decreasing) the number of taxis. 4 Alternative Regime: Entry Price Regulation Given the demonstrated disadvantages of the traditional cap on taxi numbers, is there an alternative approach to entry management that might be more effective? One such approach is to replace traditional quantity based restrictions with price based restrictions. Placing a cap on taxi licensing is a quantity-based restriction. It can be shown that for any quantity restriction, there is an equivalent pricing policy that will achieve the same result in terms of taxis and service level. For example, consider a traditional quantity based restriction of the hypothetical Midville. If Midville has a cap of 2,000 taxis, then there will be a going market rate for the lease of the taxi permit of, say, $L per year. The entry price-regulation alternative for Midville is for the regulator to set an annual licensing fee of the same $L, but with no explicit cap on taxi numbers. The result will be the same number of taxis (2,000 in this case). In the open market there is a relationship between the number of taxis and the lease price. For any quantity of taxis, there is a corresponding market clearing lease price on the permit. Any given price-quantity pair can be accessed either by capping the quantity and letting the price adjust, or by fixing the lease price and letting the quantity adjust. The traditional method is to fix the quantity, however the same result can be achieved by fixing the lease-price and letting the quantity of taxis adjust to match. Box 2 illustrates this principle. Long Run Advantages: Escaping Regulatory Capture One of the attractions of entry-price regulation is that it removes the great danger of taxi caps lagging behind growth in taxi demand. Once the price barrier is set, quantity adjusts automatically. As demand expands, the usual market competition causes the number of new taxis and/or taxi companies to rise to meet that demand. Those who can find the business to justify an additional taxi are free to pay the fee and have that taxi. The automatic adjustment of taxi numbers reduces the likelihood of regulatory capture (at least with respect to taxi numbers). In the traditional quantity capped regime, initiative is required to change the number of taxis. Under entry-price regulation, the only initiative required is for the new taxi operator to go the regulator’s counter and pay the entry fee. Page 17 of 23 Automatic Market Adjustment of Taxi Numbers under Entry-Price Regulation A virtue of entry-price regulation is that if the regulator does nothing, market forces will expand the number of taxis to meet any increase in taxi user demand. This can be shown in the lease market for taxi permits. In year one, the regulator establishes an annual license fee high enough to deter entry, but not so high as to unduly restrict supply. In effect, the regulator is leasing permits at price L1. The area of the purple square is revenues to the public purse. When demand expands to D5 in year five, taxi providers take out more permits to meet the demand they experience. Taxi supply expands to Q5. Revenues to the public purse expand, and the lease price remains at the nominal level originally set by the regulator. Year One $ Lease Taxicab Permit . (Optimal L5 D1 Public Purse Barrier to Entry) Passenger Surplus . Passenger Surplus L1 Year Five $ Lease Taxicab Permit Q1 D1 Public Purse Q1 Quantity of Taxicabs D5 Q5 Quantity of Taxicabs Compare this result to how a regime with capped permits might experience an increase in taxi demand (diagram below from Text Box 1). In year five, entry-price regulation shows a larger number of taxis, larger passenger surplus, and there is no deadweight loss. $ Lease Taxicab Permit $ Lease Taxicab Permit Year One L5 Passenger Surplus L1 Passenger Surplus . (Inflate Lease d Price) . Producer DW Loss D1 Producer Q1 Box 2 Year Five D1 Quantity of Taxicabs Q1 D5 Q5 Quantity of Taxicabs Page 18 of 23 Additional advantages of entry-price regulation: Switching is possible in mature regimes. The switch from quantity- to price-based restriction can occur at any time. Even where permit values have been allowed to climb to an unreasonable level, a switch to open entry combined with a license fee equal to current annual permit leases will prevent further deterioration, and ensure that future increases in taxi demand are met automatically with increased service provision from new permits requested by the industry. Compromises can protect incumbent interests. Holders of existing permits can be grandfathered into a price-regulated permit regime, and continue to collect their lease rents. The difference is that lease values will not climb above the alternative offered by the regulator of new permits for the entry-limiting annual fee. Old permit holders will retain their income stream, although they may lose any speculative value of their permits embodying future expectations of continued regulatory capture. Gain to public purse. The revenue from the new higher priced taxi permits goes to the public purse. Improved competition and innovation. New taxi companies can enter the market without having to negotiate buyouts of existing firms. Arguably, it takes a fleet of at least 100 taxis to provide efficient dispatch service to a city of reasonable size. Under entry-price regulation, a new entrant is free to enter at scale, risking the entry price in the belief that they have a better service or can serve new submarkets. Under capped taxi permits, a serious new entrant at the company level must find a minimum of 100 taxi permits from existing providers. This imposes a barrier to new entrants at two levels: the actual licenses; and the need to be geographically close to manage such a deal when purchasing from a multitude of small operators (large incumbents are unlikely to cooperate). This makes it difficult for companies from other cities to bring their successful innovations to the city in question. Improved treatment of drivers. In a regime, with capped taxi permits, drivers without those permits often experience poor working conditions. Available permits may be held by relatively few companies, and drivers may feel unable to resist exploitation by those who own the right to the driver’s ability to work. When drivers have the choice of leasing existing plates, or paying the same amount to the regulator for an annual permit, they are empowered to reject unfair working conditions. Experience with Tariff Quotas Although entry-price regulation is a logical alternative, it is difficult to find examples of taxi regimes combining open-entry with deterrent level annual licensing fees. One reason may be that, having overcome industry objections to opening taxi numbers, governments find auctioning taxi permits more attractive than stepping into the place of permit lessors. Getting $490,000 per new permit up front may be more attractive than an annual stream of $35,000.28 The immediate yield in funds is higher from auctions, and municipal budgeting may treat license revenues as a capital acquisition, with fewer 28 The approximate permit value and corresponding lease value advertised for Melbourne as of March 2012. Page 19 of 23 spending restrictions than annual revenues from permit fees. If immediate revenue is the objective, maintaining a regime of fixed caps on taxis ensures a better auction price. There is a parallel policy area where price regulation has been used as a substitute for quantity regulation: import quotas. Many countries set quotas on imports as a form of trade protection. Over time, these quotas acquire value in a similar fashion as taxi permits. As world economies and trade expand, import quotas can lag in adjusting to a country’s need, frustrating would-be buyers domestically as well as foreign suppliers. In the 1995 Uruguay round of GATT negotiations, import quotas became a major concern, particularly for agricultural products. Less developed nations wanted access to developed markets, and saw quotas as a barrier. The negotiated result centred on tariffication of quotas, by converting a fixed quota to the right to import at a preferred rate, while additional imports were permitted at a higher rate of tariff. The result is termed the tariff rate quota (TRQ). While the declared intent was to improve access to markets for developing countries, the measures also permitted importing nations to protect the incumbent holders of import quotas, while at least partially opening trade at higher tariff levels. As a program to improve market access for developing countries, the TRQ programs from the 1995 Uruguay round are largely thought to have been ineffective. In many cases, individual countries imposed other nontariff barriers to limit their effect.29 However, TRQ’s remain an example of how quantity-based restrictions can be converted to price-based restrictions, while protecting the interests of incumbent permit holders. Entry Price by Permit Sale or Lease? Our analysis of price regulation has focused on regulating entry by setting a high enough annual license fee to deter excess entry. A second alternative is to sell the taxi permit itself for a fixed price. The approach is different from auctioning, in that the price is fixed while the number of permits available is open to the number willing to pay that price. Outright sale of taxi permits results in more immediate revenue than annual fees. In the long run, however, revenue to the public purse may be less. Lease payments on permits usually represent a high rate of return. Melbourne’s 2012 lease rate of approximately $35,000 per year is a 7% yield, compared to contemporary long-term government bond yields of 4%. The higher rate of return reflects the perceived risk of regime change (such as deregulation), and the usual market risks of return on any security.30 Because the regulator internalizes this risk, opting for annual lease value over sale offers the same financial benefit as taking sale revenue and investing it at a rate of return above market. The present value of the annual permit fee exceeds the sale price of the permit. Another disadvantage of regulator selling over leasing is the uncertain obligations it creates for the regulator. In the British legal tradition, regulators who control the price of services (i.e. meter rates) 29 Abbot, Philip C. Tariff rate quotas: Failed market access instruments? 77th EAAE Seminar / NJF Seminar No. 325, August 17-18, 2001, Helsinki 30 Returns on any security are partly determined by their portfolio value in diversifying risk. Because taxi industry returns are highly correlated with economic conditions, taxi permits are riskier in this sense and command a lower price for a given expected annual return. Page 20 of 23 have an obligation to ensure fair and reasonable or just and reasonable returns to investors in that industry. Meeting this obligation is not normally a concern of taxi regulators. Market prices for taxi permits are prima facie evidence that returns within the taxi industry are higher than generally available elsewhere. That is why individuals are willing to pay to enter the industry by purchasing permits. When a regulator takes a direct role in selling the permit, there may be an unknown obligation to include consideration of the sale price in the calculation of fair and reasonable rates of return. Inclusion of the artificial cost of the taxi permit in the regulatory rate base would have far-reaching consequences, perhaps tying the regulator’s hands in future options for liberalizing the industry. In contrast, the annual license fee, even at entry deterring levels, does not involve any implied promise beyond the year for which the permit was issued. Other advantages of entry-price management by leasing over selling include: 5 Better protection of drivers. As noted above, drivers who have the option of paying their lease fee to the regulator instead of to a traditional taxi permit holder are more clearly empowered to resist exploitation. If the alternative requires financing a $490,000 purchase, the choice is less feasible. Improved competition and innovation. New entrants will find it easier to finance the annual fee for 100 new taxi permits than to purchase 100 new permits. The policy objective is to deter excess entry driven by unemployment, not to deter competition and innovation. More accurate regulation. It is easier for the regulator to set an annual fee directly rather than estimate the implied barrier to entry from the capital cost of a permit sale. Summary and Comparison of Entry Management Regimes Table 3 compares the five entry-management regimes discussed here: 1. Open entry. The default regime in the absence of entry control. Analysis assumes the choice of entry management regime is made within the usual framework of taxi regulation. This includes training, testing, and criminal record checks for drivers, vehicle standards and inspection, and regulated meter rates. 2. Quantity regulation of taxis using a cap on taxi numbers: Setting a cap on the total number of taxis permitted (the current dominant model). 3. Quantity regulation of taxis using service standards: This is a variant of quota regulation where the regulator takes advantage of modern technology to monitor service standards directly from taxi company data systems and management reports. For example, the regulator might target 80% of dispatch trips to have meter-on within 15 minutes. When the service standard declines, additional taxi permits are issued to bring service back to desired levels. 4. Entry-price regulation of taxis through selling permits: Regulating the number of taxis indirectly by setting a sale price for taxi permits high enough to deter excess entry. 5. Entry-price regulation of taxis using annual fees: Regulating the number of taxis indirectly by setting a high annual fee (equivalent to the lease price of a permit), to deter excess entry. Table 3: Comparing Entry Management Regimes Regime 1. Open Entry 2. Quantity Regulation (cap on taxi numbers) 3.Quantity Regulation (service standards) 4.Entry-Price Regulation (annual fees) 5. Entry-Price Regulation (sale of permits) National Wealth & Productivity Taxi Industry Broader Economy Lower service quality as excess entry during recessions chases experienced drivers out of market. Avoids excess entry, but regulatory capture causes cap to lag demand growth. The result is: Higher meter rates. Longer wait times. Deadweight loss from suppressed taxi demand. Low competition and innovation. Avoids excess entry. Risk of capture reduced but still present. Link to objective industry performance data improves likelihood of good management of permit cap. Minor costs to industry to provide basic reports. Opportunity to link to broader technological reform and full reporting of individual trips. Taxi numbers expand automatically at minimum required barrier to entry and reduced likelihood of capture. Relative to capped regimes there is: No lag in adjustment of taxi numbers. Less suppressed taxi demand. Improved competition and entry of competitors at efficient of scale. Fairer working conditions for drivers. Same as annual fee price control above except benefits of increased competition and improved driver working conditions are reduced. Fairness & Political Sustainability Government Fiscal Impact Largest supply of taxis to other sectors. Difficult to sustain. Periodic low driver income from excess entry during recessions tends to force capped regime. Higher enforcement costs due to marginal operators during recessions, and higher ongoing driver turnover. Excess restrictions in taxi capacity result in: Lower public transit ridership along with increased congestion, pollution, and road network costs. Lower ability to accommodate growing numbers of persons with disability in an aging population. Ineffective policies to revive downtown cores and reduce drunk driving. Entrenched interests of private permit holders perpetuate regime in which: Customers pay too much or wait too long. Excess payment goes to permit holders, not drivers. Reduced administrative costs due to longer term players and absence of excess entrants. As above, but with reduced risk due to lower likelihood of regulatory capture. Avoids negative impacts of excess supply restrictions. Avoids negative impacts of excess supply restrictions. As above, but with reduced risk of capture. Possibility of preventing further deterioration by converting current performance to a performance standard. Additional cost of receiving and processing reports and data. Minor if requiring management report. Larger if requiring real-time access to individual trips. Compromises can protect incumbent interests by grandfathering old permits. Can be applied to cap license number regimes so as to protect incumbent interests, while avoiding further lag of taxi numbers below demand. Increased revenues from entry-deterring annual permit fees. Continued entrenchment of vested interests with purchased licences. Risk of capture. Increased revenue from sale of permits, but lower net present value than ongoing permit sales. Page 22 of 23 Regimes are compared in terms of national wealth and productivity, fairness and sustainability, and government fiscal impact. In brief, the unique nature of the taxi industry risks excessive entry by the unemployed during economic downturns. This in turn lowers taxi driver incomes, driving good quality drivers out and raising enforcement costs. The income crisis within the industry accounts for why open entry is difficult to sustain politically—traditionally resulting in capped numbers of taxis. In theory, caps could be set at only mild restrictions. In fact, this is usually the case with a license freeze imposed at the moment of excess supply, sometimes rationalized as temporary. Over time, regulatory capture means caps tend to lag behind demand growth. The result is restricted supply, high permit values, higher meter rates and/or customer wait times, drivers being forced to pay to lease permits, and deadweight losses from restricted demand. Permit values increase to levels far in excess of what is required to deter entry by the unemployed. Driver working conditions tend to decline as control of the permits become concentrated in a few hands. The restricted supply also has negative impacts on public transit use, accommodation of persons with disability, reduction of drunk driving, and revival of downtown cores. Losses from lagged cap regimes are proportionate to the degree of suppressed demand. Demand elasticity estimates suggest moderate percentage losses, but per capita estimates and the experience of liberalized regimes suggest that the potential taxi demand may be up to triple revealed demand. This is a strong argument against permit caps. A potentially more effective method of managing permit caps is to set performance targets based on actual dispatch response times, and similar measures, as reported by computer dispatch systems. The technical capability of doing this is well established, but the method is not in widespread use. This approach offers a more effective policy rule linking taxi numbers directly to industry performance. However, implementation still takes place within a managed cap on the number of permits, and the risks of regulatory capture remain. Implementing this approach requires more data collection from industry than is usual for regulators. Opportunities to change the data reporting relationship may occur if the regulator is also considering incorporating higher technology in the back seat of taxis to improve user experiences. When installing GPS and credit card enabled devices, systems can also be upgraded to report real-time trip data to the regulator. Entry-price regulation offers an alternative approach to controlling taxi entry. Annual license fees, or equivalent sale of permits, can be set to levels high enough to deter excess entry by the unemployed, but not so high as to significantly suppress taxi demand. Once set, the number of taxis automatically expands with demand as competitors in the industry respond. Vulnerability to industry capture is reduced, taxi driver working conditions improve as drivers have alternative sources of permits; and new competition can enter at scale by acquiring new permits directly from the regulator. Of the two methods of entry-price management, use of annual fees appears to have the advantage over direct sale of permits. The annual fees approach yields greater fiscal rewards in the long run, and involves lower barriers to new firms wishing to enter at scale. The direct sale of permits my also imply Page 23 of 23 unknown obligations to permit purchasers to ensure a regime that continues to justify the price paid. Annual permits represent commitments only for that year, preserving policy flexibility. Traditional capped regimes can be converted to entry-price regulation, while protecting incumbent interests, by setting annual fees equal to prevailing lease rates and grandfathering existing permit holders. While this involves preserving the high barrier to entry from the previous regime, future adjustments in taxi numbers will be open and automatic in response to industry growth. Previous permit holders in such a conversion would continue to receive their established income stream, but would lose any speculative value in their permits not justified by that stream. This compromise prevents further damage, and provides some comfort to current industry participants.