Briefing Note

advertisement

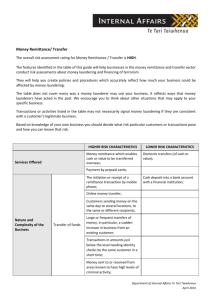

Briefing Note The Hawala System & the International Monetary Fund / Financial Action Task Force The omnipresence of the Al-Qaeda with its obdurate mantra placed ‘Alternative Remittance Systems’ (ARS) at the fore of the counter-terrorism campaign.1 The depth and extent of ARS is hard to fathom because it allows if not encourages a degree of subreption. ASRs are widespread; they operate in advanced economic systems where the financial system operates efficiently,2 and in dysfunctional or less-developed financial systems.3 The International Monetary Fund (IMF) with the support of such organisation as the Financial Action Task Force (FATF), the United Nations Office of Drug and Crime (ODC) and the World Bank has endeavoured to come to grips with ASRs, as ASRs undermine the general financial system and fall prey to nefarious elements.4 The purpose of this paper is to review a specific ASR system, the hawala system. The paper emphasis is laid on the purpose and some of the advantages that hawala offers its users. In the second part, the focus shifts to analysing some of the actions taken by the IMF and the FATF in their campaign to combat the hawala system. The paper concludes by providing some suggestions as to deal with the hawala system. On the importance of dealing with the finance of terrorism see for example: Mathew Levitt “Stemming the Flow of Terrorist Financing: Practical and Conceptual Challenges” The Fletcher Forum of World Affairs Vol. 27, No. 1 (Winter/spring 2003). Available on line at: http://www.intelligence.org.il/eng/bu/financing/articles/terror%20financing%20-%20Fletcher.pdf 2 “Suppressing the Financing of Terrorism: A Handbook for Legislative Drafting” Legal Department International Monetary Fund (2003): 31. 3 See for example the role of hawala in Afghanistan, Samuel Munzele Maimbo “The Money Exchange Dealers of Kabul: A Study of the Hawala System in Afghanistan” Finance and Private Sector Unit South Asia Region, World Bank (June 2003): 5. Available on line at: http://www1.worldbank.org/finance/html/amlcft/docs/(06.23.03)%20The%20Hawala%20System%20in%20Afgh anistan%20(Maimbo).pdf#search='Purpose%20of%20Hawala' 4 Malkin and Elizur have claimed that comparing the Clinton and George W. Bush approach to money laundering as comparing apples and oranges, as following 9/11, terrorist financing and money laundering became a central theme in the ‘war on terror’. They write, “The Clinton people treated money laundering as a problem to be solved by bureaucrats because there was little hope of help from Congress. Officials came at it as a weapon to defend human rights by taking down corrupt dictators… The current Bush administration treats money laundering strictly as a law enforcement matter backed by diplomacy and is able to do so precisely because it was handed the legal authority by Congress.” Lawrence Malkin & Yuval Elizur “Terrorism’s Money Trail” World Policy Journal Vol. XIX, No.1, (Spring 2002): 60-61. 1 What is Hawala Hawala is one of the ARS or Informal Funds Transfer (IFT) systems available for the transfer of money or assets around the globe.5 IFTs operate domestically and internationally, as in some countries (particularly war/conflict-afflicted) the local population use it to transfer funds around the country. It also has a global-reach as it facilitates the sending of funds from one side of the globe to the next. In the context of IFT, ‘hawala’ refers to an informal way to transfer funds from one location to another via an intermediary (service providers) known as ‘hawalandars.’6 In Arabic, the term hawala means ‘transfer’ or ‘wire.’ The system exists in China (FeiCh'ien), Philippines (Padala), India (Hundi), Hong Kong (Hui Kuan), and Thailand (Phei Kwan). The distinguishing feature of hawala is its reliance on trust. Consequently, the system principle users are family members or members of the same region/community who make use of it to send money around the globe.7 There are two types of hawala systems the ‘white hawala’ and the ‘black hawala.’ The former deals with money from licit sources while ‘black hawala’ refers to the transfer of money or assets obtained from illicit sources. This briefing note focuses principally on the former, though when seeking to deal with the ‘white hawala’ one must also consider the ‘black hawala’ as criminals and terrorists manipulate the general hawala system.8 Purpose of Hawala The hawala system emerged to finance trade without having to travel with gold or silver, which used to be dangerous, as roads used to be beset with pirates and bandits. The system flourished in China, Asia and the Middle East.9 5 There are various names for the system with the most common being: Informal Funds Transfer System (IFTS); Informal Value Transfer System (IVTS) or Alternative Remittance System (ASRs). 6 Mohammad El-Qorchi “Hawala” Finance and Development Vol. 39, No. 4, (December 2002); Mohammad ElQorchi “Hawala: Based on Trust, Subject to Abuse” Economic Perspective (September 2004). Available on line at: http://usinfo.state.gov/journals/ites/0904/ijee/ijee0904.pdf 7 Mohammad El-Qorchi “Hawala” Finance and Development Vol. 39, No. 4, (December 2002); Mohammad ElQorchi “Hawala: Based on Trust, Subject to Abuse” Economic Perspective (September 2004). Available on line at: http://usinfo.state.gov/journals/ites/0904/ijee/ijee0904.pdf 8 Examples of hawala abuse range from narcotic trafficking, illegal arms trade, subsidy, welfare and customs fraud, tax and embargo violations, gold smuggling, etc. 9 The Chinese fe ch’ien (“flying money or coin”) emerged in the latter part of the T’ang Dynasty due to increase internal trade. Southern traders used the system to sell goods such as tea at the capital and transfer their revenues back home through liaison offices or agencies of provincial governments located at the Imperial Court. The revenues were used to pay taxes due from the provinces to the central government, without having to transfer large sums of money overland were robbers could attack the shipments. Leonides Buencamino & Sergei Gorbunov “Informal Money Transfer System: Opportunities & Challenges for Development Finance” DESA Discussion Paper No. 26 (United Nations: November 2002) (ST/ESA/2002/DP/26). The current primary users of IFTs are individuals from the Indian subcontinent, East Asia, Africa, Eastern Europe, and elsewhere who live and work in Europe, the Persian Gulf region, and North America. These individuals send remittances to their relatives back home. 10 This has led R. Barry Johnson to note that although IFTs have increasingly come under scrutiny because terrorists and criminals use them, “…remittances are very important to migrant workers who send money home and that IFT systems represent an important source of income for some countries.”11 In addition, to migrant workers, other users of the system range from legitimate companies, government agencies, NGOs, individual traders, etc. Hawala also operates as a settlement process under which the intermediaries settle their accounts and that may lead to money transfer or the exchange of goods and services. Why Use Hawala The hawala system provides an array of advantages for its users. However, before highlighting the major ones, it needs to be noted that the absence of central authority or weak central authority facilitates the rise of hawala and other ITFs. Thus, in Somalia for example, the absence of central government and effective infrastructure encouraged the emergence of the system while in Afghanistan incessant violence (especially in the last few decades) undermined the official financial system.12 In the words of one commentator referring to the Afghanistan situation, “…hawala has provided the most reliable, convenient, safe, and inexpensive means of transferring funds to far- flung regions.”13 This view could and does apply globally. It is especially apparent in the less-developed world where the financial system is more open to abuse and manipulation by officials and criminals. It is noteworthy that in the less-developed world the allure of embezzlement by bank officials is greater because of the low pay received by employees. This enables criminal elements to use financial inducements to persuade officials to bypass banking laws. 10 The World Bank believes that migrant workers remittance stood at around $110 billion in 2004 compared to $93 billion in 2003. Dawn April 5, 2004. Available on line at: http://www.dawn.com/2005/04/05/ebr10.htm 11 R. Barry Johnston “Work of the IMF in Informal Funds Transfer System” in Regulatory Frameworks for Hawala and Other Remittance Systems. Monetary & Financial Systems Department, International Monetary Fund, (Washington: IMF Multimedia Services Division, 2005): 3. 12 The Taliban eschewed the non-Islamic financial system with Mullah Mohammed Omar distributing money from a tin box. Ahmed Rashid Taliban: The Story of Afghan Warlords (London: Pan Books, 2001) 13 Samuel Munzele Maimbo “The Money Exchange Dealers of Kabul: A Study of the Hawala System in Afghanistan” Finance and Private Sector Unit South Asia Region, World Bank (June 2003): 5. Available on line at: http://www1.worldbank.org/finance/html/amlcft/docs/(06.23.03)%20The%20Hawala%20System%20in%20Afgh anistan%20(Maimbo).pdf#search='Purpose%20of%20Hawala' The advantages of IFTs are numerous, and thus within the context of this briefing note, only a few would be mentioned. First, IFT is anonymous. The person sending the funds from Country A to a beneficiary in Country B deals only with the hawalandar who provides the customer with an authentication code which the customer transmit to his beneficiary. The beneficiary collects the equivalent amount of the money from another hawalandar, which his benefactor had deposited with the hawalandar in Country A. There is no need for paper (evidence) as the transaction could take place orally or even through the internet in a chat room.14 Under the hawala system, the Customer (the person sending the money) does not need to open a bank account in the country from which he is sending the money nor does the beneficiary need a bank account. Moreover, there is often a door-to-door service, which helps those who are sending money back to ailing or infirm family members. Second, the system is swifter than the formal banking system, which requires scrutiny over large money deposits to ensure it is not tainted.15 International wire transfer takes considerable time, normally around a week as for example the source of money needs to be examined due to domestic and international regulations. There are also different working practices and other differences that prevent the quick transference of funds from one country to another. Under the hawala the money (cash) could be in the hands of the beneficiary within 24 hours. Holidays, weekends, time differences have little if any affect those using hawala. Moreover, there are instances where conventional banking facilities do not exist, which leas to the emergence of hawala.16 Third, the system relies on kinship, ethnic ties or personal relationship between the hawalandars and their customers, which at times meant that funds could be sent before they are deposited with the initial hawalandar.17 Linked to this is the issue of reliability (trust) with On the clientele and ‘paper trail’ aspect see for example Lisa C. Carroll “Alternative remittance systems distinguishing sub-systems of ethnic money laundering in Interpol member countries on the Asian continent” Interpol (December 5, 2005). Available on line at: http://www.interpol.com/Public/FinancialCrime/MoneyLaundering/EthnicMoney/ 15 On the British money laundering legislation see for example: Robert Rhodes & Serena Palastrand “A Guide to Money Laundering Legislation” Journal of Money Laundering Control Vol. 8, No. 1 (September 2004): 9-18. For the American requirements see for example, Courtney J. Linn “How Terrorists Exploit Gaps in US AntiMoney Laundering Laws to Secret Plunder” Journal of Money Laundering Control Vol. 8, No. 3 (March 2005): 200-214. 16 Buencamino and Gorbunov note that IFTs emerged between Australia and Africa because of a lack of formal banking linkage between Australia and several African countries. Leonides Buencamino & Sergei Gorbunov “Informal Money Transfer System: Opportunities & Challenges for Development Finance” DESA Discussion Paper No. 26 (United Nations: November 2002) (ST/ESA/2002/DP/26). 17 Mohammad El-Qorchi “Hawala” Finance and Development Vol. 39, No. 4, (December 2002). 14 the hawalandars rarely failing to make a payment as they know that such a thing would end their involvement in the sector.18 Fourth, the system is cheaper, as the hawalandars although charging a fee or commission (0.25% to 1.25% of the amount involved), still demands a lower rate than the formal financial system, (they incur less overhead expenses coupled with their disregard of regulations).19 Furthermore, because there is often an element of kinship is involved payment may take a variety of forms such as goods and services (medical help, housing, etc.)20 The Role of the IMF & FATF in countering Hawala The Financial Action Task Force (FATF) emerged in 1989 following the G-7 Summit in Paris. Its aim was to combat the increasing threat that money laundering posed the banking system and financial institution. To this end, the FATF was entrusted with the responsibility of examining money laundering techniques and trends. This involved the FATF reviewing the national and international action and setting out what needs to be done to combat money laundering. Within a year, the FATF issued a report containing a set of Forty Recommendations, which provide a comprehensive plan of action needed to fight against money laundering.21 FATF works closely with other international institutions such as the IMF, the World Bank, the United Nations and FATF-style regional bodies (FSRBs) to IFTs. The FATF Eighth Special Recommendations deal specifically with the issue of counter terrorism financing. Earl Anthony Wayne, the Assistant Secretary, Bureau of Economic and Business Affairs, has stated that the FATF Eight Special Recommendations on Terrorist Financing “…have become the international operational standard on addressing terrorist financing.”22 The First Recommendation emphasises the importance of universal ratification of the 1999 United Nations International Convention for the Suppression of the Financing of Terrorism Samuel Munzele Maimbo “The Money Exchange Dealers of Kabul: A Study of the Hawala System in Afghanistan” Finance and Private Sector Unit South Asia Region, World Bank (June 2003): 5. Available on line at: http://www1.worldbank.org/finance/html/amlcft/docs/(06.23.03)%20The%20Hawala%20System%20in%20Afgh anistan%20(Maimbo).pdf#search='Purpose%20of%20Hawala' 19 Leonides Buencamino & Sergei Gorbunov “Informal Money Transfer System: Opportunities & Challenges for Development Finance” DESA Discussion Paper No. 26 (United Nations: November 2002) (ST/ESA/2002/DP/26). 20 On the reverse hawala see Mohammad El-Qorchi “Hawala” Finance and Development Vol. 39, No. 4 (December 2002). 21 For the history of the FATF see the FATF website: http://www.fatf-gafi.org/document/63/0,2340,en_32250379_32236836_34432255_1_1_1_1,00.html 22 E. Anthony Wayne “Internationalizing the Fight” Economic Perspective (September 2004). Available on line at: http://usinfo.state.gov/journals/ites/0904/ijee/ijee0904.pdf 18 and the Security Council Resolution 1373. The Convention, which more than one hundred countries have ratified states that it is an offence to directly or indirectly provide or collect funds with the intention or knowledge that they would be use for terrorist activities.23 The Convention demands that States introduce legislation making it a criminal offence to finance terrorism. States must also cooperate with other states and provide each other with legal assistance in the matters covered by the Convention. Finally, States have to impose various requirements on their financial institution vis-à-vis the detection and reporting evidence of financing of terrorist acts.24 Security Council Resolution 1373 declared that the 9/11 attacks amounted to a threat to international peace and security. The legal implication for such a declaration is that it allows the Council to take, if it deems it necessary, collective measures under Chapter VII or Chapter VI (sanctions). The measures must be adopted by the Member States of the United Nations (Article 25,25 4826 of the UN Charter). On the issue of terrorist financing requires that states “prevent and suppress the financing of terrorist acts” and criminalise the wilful collection, whether direct or indirect, of funds for terrorist acts. Under paragraph 1(d) of 1373, UN Member States are required to “Prohibit their nationals or any persons and entities within their territories from making any funds, financial assets or economic resources or financial or other related services available, directly or indirectly, for the benefit of persons who commit or attempt to commit or facilitate or participate in the commission of terrorist acts, of entities owned or controlled, directly or indirectly, by such persons and of persons and entities acting on behalf of or at the direction of such persons.”27 The Convention defines ‘terrorist acts’ if they appear in at least those of the nine international treaties listed in the Annex to the Convention to which the country is a party (“treaty offences”). Secondly, terrorist acts are also defined in the generic definition set out in Article 2(b) of the Convention (“generic offences”). For the Convention see: http://untreaty.un.org/English/Terrorism/Conv12.pdf#search='United%20Nations%20International%20Conventio n%20for%20the%20Suppression%20of%20the%20Financing%20of%20Terrorism' See also: “Suppressing the Financing of Terrorism: A Handbook for Legislative Drafting” Legal Department International Monetary Fund (2003): 46. 24 “Suppressing the Financing of Terrorism: A Handbook for Legislative Drafting” Legal Department International Monetary Fund (2003): 31. 25 Article 25 states: “The Members of the United Nations agree to accept and carry out the decisions of the Security Council in accordance with the present Charter.” Available on line at: http://www.un.org/aboutun/charter/ 26 Article 48(1) states: “The action required to carry out the decisions of the Security Council for the maintenance of international peace and security shall be taken by all the Members of the United Nations or by some of them, as the Security Council may determine.” Article 48(2) states “Such decisions shall be carried out by the Members of the United Nations directly and through their action in the appropriate international agencies of which they are members.” Available on line at: http://www.un.org/aboutun/charter/ 27 United Nations Security Council 1373, September 28, 2001. S/Res/1373 (2001). See also “Suppressing the Financing of Terrorism: A Handbook for Legislative Drafting” Legal Department International Monetary Fund (2003): 20-21. 23 The Second Recommendation notes the importance of domestic legislation and the need to make the financing of terrorism a criminal act. There has been significant development regarding the domestic criminalisation of terrorist finances according to the reports that states have submitted to the UN Counter-Terrorism Committee (as required under Security Council Resolution 1373).28 The Third Recommendation building on Resolution 1373 and the 1999 Convention centres on the freezing of terrorist funds or assets. The importance of domestic legislation in this field is emphasised by the FATF. The FATF placed in the Third Recommendation two obligations, the first is the freezing of terrorist funds or assets to prevent terrorist activity. Moreover, it also sought through the Recommendation to deprive the ‘terrorists’ of the funds to carry out their nefarious activities.29 The Fourth Recommendation points to the need for countries, businesses and other entities to notify the competent authorities if they suspect that funds are somehow relates to, or are to be used for terrorism, terrorist acts or terrorist organisations. The FATF Guidance Notes points to two key elements: “Jurisdictions should establish a requirement for making a report to competent authorities when there is a suspicion that funds are linked to terrorist financing;” and, “Jurisdictions should establish a requirement for making a report to competent authorities when there are reasonable grounds to suspect that funds are linked to terrorist financing.”30 The Fifth Recommendation builds on the need for international cooperation. It calls on countries to notify and/or exchange information on matters relating to the financing of terrorism. It has five elements:31 1. Countries need to establish legal avenues to exchange regarding terrorist financing; 2. Countries need to develop ways to exchange information regarding terrorist financing by means other than legal assistance mechanisms; 3. Countries must adopt specific measures to prevent individuals involved with terrorist financing from having “safe haven”; 28 The reports are available on the website of the Security Council Counter-Terrorism Committee website: http://www.un.org/Docs/sc/committees/1373/ 29 ‘Interpretative Note to Special Recommendation III: Freezing and Confiscating Terrorist Assets’ in the FATF Interpretative Notes to the Nine Special Recommendations on Terrorist Financing. Available on line at: http://www.fatf-gafi.org/document/53/0,2340,en_32250379_32236947_34261877_1_1_1_1,00.html#inSRIII 30 Guidance Notes for the Special Recommendations on Terrorist Financing and Self-Assessment Questionnaire FATF Secretariat (March 27, 2002): 3. Available on line at: http://www.fatf-gafi.org/dataoecd/39/20/34033909.pdf 31 Guidance Notes for the Special Recommendations on Terrorist Financing and Self-Assessment Questionnaire FATF Secretariat (March 27, 2002): 4. Available on line at: http://www.fatf-gafi.org/dataoecd/39/20/34033909.pdf 4. Countries need to adopt extradition procedures regarding individuals involved in terrorist financing; 5. Countries should establish provisions or procedures to ensure that “claims of political motivation are not recognised as a ground for refusing requests to extradite persons alleged to be involved in terrorist financing”. Under the Sixth Recommendation, the FATF took the unprecedented step of calling on persons or legal entities that provide a service of money or asset transmission to be licensed or registered. The FATF realising that the financial system is open to manipulation and abuse wants to make it more transparent. The key element is the need for licence/registration for those who provide money/value transfer services whether through informal or formal channels.32 The Seventh Recommendation was innovative as it called on states to adopt measures under which financial institutions obtain and hold information on the sender (name, address, account number etc.). It specifically focused on wire transfer, domestic and international.33 The Eight Recommendation dealt with non-profit organisations as they are vulnerable to abuse, and therefore countries need to adopt measures to prevent such abuse. The FATF Guidance Notes refer to the need for establish jurisdiction that would review “the legal regime of entities” with special emphasis placed on non-profit organisation to ensure that such groups are not used by terrorist organisations. More specifically the Recommendation focused on preventing terrorist organisation from using non-profit organisations “…to disguise or facilitate terrorist financing activities, to escape asset freezing measures or to conceal diversions of legitimate funds to terrorist organisations.”34 The Ninth Recommendation (adopted on October 22, 2004) noted that danger posed by money couriers and called on countries to adopt measures to detect the physical cross-border movement of currency and bearer negotiated instruments.35 ‘Interpretative Note to Special Recommendation VI: Alternative Remittance’ in the FATF Interpretative Notes to the Nine Special Recommendations on Terrorist Financing. Available on line at: http://www.fatf-gafi.org/document/53/0,2340,en_32250379_32236947_34261877_1_1_1_1,00.html#inSRIII 33 ‘Interpretative Note to Special Recommendation VII: Wire Transfer’ in the FATF Interpretative Notes to the Nine Special Recommendations on Terrorist Financing. Available on line at: http://www.fatf-gafi.org/document/53/0,2340,en_32250379_32236947_34261877_1_1_1_1,00.html#inSRIII 34 Guidance Notes for the Special Recommendations on Terrorist Financing and Self-Assessment Questionnaire FATF Secretariat (March 27, 2002): 6-7. Available on line at: http://www.fatf-gafi.org/dataoecd/39/20/34033909.pdf 35 “FATF Standards: Nine Special Recommendations on Terrorist Financing”. Available on line at: http://www.oecd.org/document/9/0,2340,en_32250379_32236920_34032073_1_1_1_1,00.html#IXCashcourriers 32 Why is it important to deal Hawala system The hawala system (the ‘white’ and the ‘black’) has proven itself highly dangerous on a multitude of levels. Firstly, it undermines the global financial system as it facilitates the transference of money without records thereby providing an eschewed financial picture. That is, the transference of unaccounted money into a country has an impact on development and growth of a country as argued by Mohammad El-Qorchi. On a macroeconomic level hawala undermines growth because although funds change hands from one country to another, as does the value, the broad money-supply remains unaltered. El-Qorchi also notes that hawala has a fiscal consequence, as tax is not paid on the remittance reducing the revenues of the remitting and receiving countries.36 The ability of those operating outside of the laws of civil society to use their ill-gotten gains to finance their continued illicit activities damages economies. On a purely moral basis, a law-based society must ensure that criminals do not operate freely. States must ensure that criminals are unable to use their ill-gotten funds to sow misery and pain. Moreover, it has been suggested that whereas hawalandars in North America may offer better-than-official exchange rates, their counterparts in the Indian subcontinent profit from offering lower rates to those willing on the rate as their prime concern is laundering their funds.37 Illegal currency manipulation harms economies on a domestically and internationally. Concluding Remarks The approach of the IMF, the FATF and other regional and international organisation in dealing with the IFTs has been impressive to date. We have come along way in a short time. The two conferences on hawala (sponsored by the United Arab Emirates) leading to the Abu Dhabi Declaration on Hawala (2002)38 emphasised the commitment of the international community (and more specifically some of the Muslim countries) to deal with IFTs. There have a variety of innovative ideas as to controlling the system: some governments have introduced migrant foreign currency accounts and bonds not subjected to foreign exchange regulations; others introduced legislation in which foreign currency accounts pay abovemarket interest rates; in Egypt and Turkey premium exchange rates are offered for the Mohammad El-Qorchi “Hawala” Finance and Development Vol. 39, No. 4, (December 2002). Lisa C. Carroll “Alternative remittance systems distinguishing sub-systems of ethnic money laundering in Interpol member countries on the Asian continent” Interpol (December 5, 2005). Available on line at: http://www.interpol.com/Public/FinancialCrime/MoneyLaundering/EthnicMoney/ 38 Available on line at: http://www.ustreas.gov/offices/enforcement/programs/Hawalaconf.pdf#search='abu%20dhabi%20declaration%20on%20hawala' 36 37 conversion of foreign currency.39 An important starting point is the realisation that not all hawala transactions assist in the illegal transfer of funds to terrorist or other nefarious organisations. The distinction is significant, as although the system is largely illegal in western economic system they play a major role in the less developed world. The Bangko Sentral ng Pilipinas has calculated that annual overseas Filipino worker remittance has increased from $103 million in 1975 to around $8.5 billion in 2004 making the Philippines the third largest recipient of migrant remittance after India and Mexico.40 At the same time, it has been difficult to determine the extent to which terrorists for example use IFTs and there is evidence to suggest that the 9/11 terrorists used the formal financial system to transfer funds.41 The international community must be aware of the danger of cracking down too hard on the hawala network, which may push its operators and users underground making them far more vulnerable to criminal manipulation. Policymakers must remember that for many migrant communities (some of whom may be unfamiliar with the ways and language of their new homes) the hawala system is the cheapest, most efficient way to provide their families with a large portion of their earnings without attraction attention. Consequently, the only way to control the system is to make the hawala unattractive to its users while also recognising the role that it plays in developing economies.42 Samuel M. Maimbo has argued that the choice between formal and informal remittance system rests principally on economics. In other words, sufficient financial incentives encourage remitters to use the banking (formal) system.43 This would at least help to reduce the ‘white hawala’ system. In trying to combat the ‘white hawala’ system the international community could begin by reducing the some of the fees charged by western financial institutions especially on individual transacting with less developed countries. That is, removing or reducing the fees Leonides Buencamino & Sergei Gorbunov “Informal Money Transfer System: Opportunities & Challenges for Development Finance” DESA Discussion Paper No. 26 (United Nations: November 2002): 8. (ST/ESA/2002/DP/26). 40 The Manila Times March 21, 2005. 41 Leonides Buencamino & Sergei Gorbunov “Informal Money Transfer System: Opportunities & Challenges for Development Finance” DESA Discussion Paper No. 26 (United Nations: November 2002) (ST/ESA/2002/DP/26). 42 Buencamino and Gorbunov note that many migrant workers in residing in the United States legally obtain additional bank cards, which allows their relatives to withdraw funds from US-based accounts at any ATM, connected to a major electronic banking network. Leonides Buencamino & Sergei Gorbunov “Informal Money Transfer System: Opportunities & Challenges for Development Finance” DESA Discussion Paper No. 26 (United Nations: November 2002) (ST/ESA/2002/DP/26). 43 Samuel M. Maimbo “The Regulation & Supervision of Informal Remittance Systems: Emerging Oversight Strategies” Seminar on Current Development in Monetary Financial Law (November 24, 2004). 39 charged on individuals sending money to their families. Such a system would require a worker having a valid passport (or working visa, or any other accepted document) and the beneficiary. Banks are already demanding that those drawing cash from account present some level of authorisation and therefore adding such a system would not cost too much to financial institutions. The Filipino Senate begun investigating charges imposed by banks on the remittances of Overseas Filipino Workers (OFWs). Senator Mar Roxas who called for the Senate investigation noted that a local bank might charge around $6 per transaction, which means that over a 12-month period, the bank would collect $72, which is equivalent to 16-day minimum wage here.44 This is a positive development as it emphasises the willingness of countries where remittance system operate to encourage people to use the established financial system. Countries such as Pakistan, which have traditionally benefited from hawala and other remittance systems have introduced legislation demanding that hawalandars register their business with the government and provide documents relating to their transactions, to ensure transparency.45 India has adopted a different approach by banning the system.46 Korean companies involved in construction projects in the Middle East dealt with informal remittance by depositing their employees’ salaries in foreign currency accounts in Korean banks. The Korean model worked because the workers were not independent, but it is an example of how some countries have dealt with informal remittance.47 At the end of the day, the growing threat posed by terrorism and criminal activities demands that the international community must continue to cooperate in improving financial regulations and share information to undermine the incentives offered by the hawalandars. The West must demand that countries in which hawala is prevalent introduce regulations as was done in Pakistan, leading US Treasury Secretary John Snow to applaud Pakistan’s attempt to curtail terror financing. He added, “Evidence of (Pakistan’s commitment) is the strong action that has been taken on money laundering, and the registration and regulation of Hawala 44 The Manila Times March 21, 2005. Gulfnews.com September 20, 2003. Available on line at: http://search.gulfnews.com/articles/03/09/20/98000.html 46 Samuel M. Maimbo “The Regulation & Supervision of Informal Remittance Systems: Emerging Oversight Strategies” Seminar on Current Development in Monetary Financial Law (November 24, 2004). Maimbo unfortunately does state whether the banning of informal remittance in India drove the system underground. 47 Leonides Buencamino & Sergei Gorbunov “Informal Money Transfer System: Opportunities & Challenges for Development Finance” DESA Discussion Paper No. 26 (United Nations: November 2002) (ST/ESA/2002/DP/26). 45 networks.”48 This is why such regional organisation as Middle East and North Africa Financial Action Task Force (MENA FATF) are important as they recognise the role that the Arab world has play in preventing terrorist finances.49 Finally, there is substantial evidence that IFTs benefit from conflict situation where central authority is either non-existent or weak (hawala grew following the partition of India, the Vietnam War, Somalia, Afghanistan etc.)50 Thus, the international community must continue to work to end conflict and political instability, demand that hawalandars join the formal banking system and use technology to cut financial costs within the formal financial sector. 48 Dawn September 20, 2003. Available on line at: http://www.dawn.com/2003/09/20/top7.htm Bahrain Tribune December 21 2005. Available on line at: http://www.bahraintribune.com/ArticleDetail.asp 50 Leonides Buencamino & Sergei Gorbunov “Informal Money Transfer System: Opportunities & Challenges for Development Finance” DESA Discussion Paper No. 26 (United Nations: November 2002) (ST/ESA/2002/DP/26). 49 BIBLIOGRAPHY Buencamino, Leonides & Gorbunov Sergei, “Informal Money Transfer System: Opportunities & Challenges for Development Finance” DESA Discussion Paper No. 26 (United Nations: November 2002) (ST/ESA/2002/DP/26). Carroll, Lisa M. “Alternative remittance systems distinguishing sub-systems of ethnic money laundering in Interpol member countries on the Asian continent” Interpol (December 5, 2005). Available on line at: http://www.interpol.com/Public/FinancialCrime/MoneyLaundering/EthnicMoney/ El-Qorchi, Mohammad “Hawala” Finance and Development Vol. 39, No. 4, (December 2002). El-Qorchi, Mohammad “Hawala: Based on Trust, Subject to Abuse” Economic Perspective (September 2004). Available on line at: http://usinfo.state.gov/journals/ites/0904/ijee/ijee0904.pdf Levitt, Mathew “Stemming the Flow of Terrorist Financing: Practical and Conceptual Challenges” The Fletcher Forum of World Affairs Vol. 27, No. 1 (Winter/spring 2003). Available on line at: http://www.intelligence.org.il/eng/bu/financing/articles/terror%20financing%20%20Fletcher.pdf Linn, Courtney J. “How Terrorists Exploit Gaps in US Anti-Money Laundering Laws to Secret Plunder” Journal of Money Laundering Control Vol. 8, No. 3 (March 2005): 200-214. Maimbo, Samuel M. “The Money Exchange Dealers of Kabul: A Study of the Hawala System in Afghanistan” Finance and Private Sector Unit South Asia Region, World Bank (June 2003): 5. Available on line at: http://www1.worldbank.org/finance/html/amlcft/docs/(06.23.03)%20The%20Hawala%20Sy stem%20in%20Afghanistan%20(Maimbo).pdf#search='Purpose%20of%20Hawala Malkin, Lawrence & Elizur, Yuval “Terrorism’s Money Trail” World Policy Journal Vol. XIX, No.1, (Spring 2002): 60-70. Masciandaro, Donato “Combating Black Money: Money Laundering & Terrorism Finance, International Cooperation & the G8 Role.” Paper prepared for the Conference “Security, Prosperity and Freedom: why America needs the G8”, Indiana University, Bloomington, June 3–4, 2004. Available on line at: http://www.g7.utoronto.ca/conferences/2004/indiana/papers2004/masciandaro.pdf#search='c ombating%20black%20money' Rashid, Ahmed Taliban: The Story of Afghan Warlords (London: Pan Books, 2001). Rhodes, Robert & Palastrand, Serena “A Guide to Money Laundering Legislation” Journal of Money Laundering Control Vol. 8, No. 1 (September 2004): 9-18. Wayne, E. Anthony “Internationalizing the Fight” Economic Perspective (September 2004). Available on line at: http://usinfo.state.gov/journals/ites/0904/ijee/ijee0904.pdf Reports Guidance Notes for the Special Recommendations on Terrorist Financing and Self-Assessment Questionnaire FATF Secretariat (March 27, 2002): 6-7. Available on line at: http://www.fatf-gafi.org/dataoecd/39/20/34033909.pdf “Suppressing the Financing of Terrorism: A Handbook for Legislative Drafting” Legal Department, International Monetary Fund (2003). “FATF Standards: Nine Special Recommendations on Terrorist Financing”. Available on line at: http://www.oecd.org/document/9/0,2340,en_32250379_32236920_34032073_1_1_1_1,00.html#I XCashcourriers Regulatory Frameworks for Hawala and Other Remittance Systems. Monetary & Financial Systems Department, International Monetary Fund, (Washington: IMF Multimedia Services Division, 2005). Interpretative Notes to the Nine Special Recommendations on Terrorist Financing. Available on line at: http://www.fatfgafi.org/document/53/0,2340,en_32250379_32236947_34261877_1_1_1_1,00.html#inSRIII