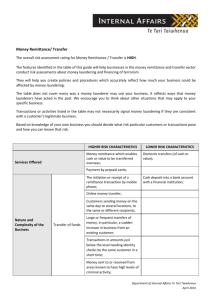

HAWALA OtHER SIMILaR SERVICE PROVIDERS IN MONEY LaUNDERING

advertisement