1. Introduction - European Parliament

advertisement

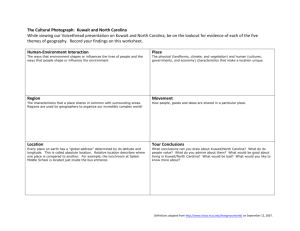

EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT DIRECTORATE-GENERAL FOR RESEARCH International and Constitutional Affairs Division PN/IV/WIP/2002/09/0007+0047 PNMMP/GD/rf Luxembourg, 20 September 2002 NOTE ON THE POLITICAL AND ECONOMIC SITUATION IN KUWAIT AND ITS RELATIONS WITH THE EUROPEAN UNION This note has been drawn up for Members of the European Parliament. The opinions it contains are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the position of the European Parliament. Sources: Economist Intelligence Unit (EIU) European Commission Eurostat Reuters Oxford Analytica World Markets Country Analysis CONTENTS Page I. POLITICAL SITUATION .................................................................................3 II. ECONOMIC SITUATION ...............................................................................10 III. RELATIONS EU/KUWAIT ..............................................................................15 ANNEXES For further information, please contact Mr Pedro Neves, European Parliament, DG IV,Division for International and Constitutional Affairs, Tel. 4300-22548, Fax: 4300-27724 / e-mail: pneves@europarl.eu.int 2 I. POLITICAL SITUATION 1. Introduction 1.1. Geographical data The Emirate of Kuwait lies in the very north-western part of the Persian Gulf, surrounded by Iraq to the north-west and by Saudi Arabia to the south. The State has a mainland and small islands (17.818 sq.km superficies). The largest island is Bubiyan, the most populous one is Failaka1. A neutral (partitioned) Zone of 5,700 sq. km lies right in the south of Kuwait, along the Gulf. The Zone is shared between Kuwait and Saudi Arabia. Much of Kuwait is an arid desert, and the climate is usually hot and humid. The official language is Arabic. English is also used in commercial circles. Kuwait city is the capital. The non-Kuwaitis, either other Arabians, are mainly Iranians, Indians and Pakistanis. Sur les quelques deux millions de personnes qui vivent au Koweït, on évalue les nationaux à moins d'un million, dont deux tiers de sunnites et un tiers de chiites. Le départ des Britanniques, au lendemain de l'indépendance, en 1962, le boom pétrolier, en 1973, puis le départ forcé des Palestiniens suite à la Guerre du Golfe en 1991 ont encouragé les grandes vagues de l'immigration asiatique. Il y a, donc, comme chez les autres monarchies du Golfe, un emploi massif d'une main-d'oeuvre immigrée au service d'une population indigène, qui, lorsqu'elle travaille, se réserve les emplois de haut niveau. En outre, les étrangers ne peuvent pas participer à la vie politique locale. 1.2. History Kuwait became a part of the Turkish Ottoman Empire in the 16th century. During the later years of Ottoman rule Kuwait became a semi-autonomous Arab monarchy, with local administration controlled by a Sheikh of the Sabah family, which is the ruling dynasty since 1756. In 1899, fearing an extension of the Turkish control, the ruler of Kuwait signed a treaty with the United Kingdom, accepting British protection while surrendering control over external relations. The Turkish sovereignty over Kuwait ended in 1918, with the dissolution of the Ottoman Empire, but since 1914, the emirate was already a British protectorate. Kuwait became fully independent on 19 June 1961, when the United Kingdom and Kuwait agreed to terminate the 1899 Treaty. Kuwait was accepted in the League of Arab States despite opposition from Iraq, which claimed that Kuwait was historically part of Iraqi territory. The first elections in Kuwait took place in December 1961. The Assembly drafted a new Constitution, which was adopted in December 1962. In 1977, Sheikh Jaber Al-Ahmad Al-Sabah became the ruler of Kuwait, its Emir. 1 see Annex I, p. 16 3 2. Domestic policy 2.1. State organization The political system is characterised by a division of power among the executive powers of the hereditary monarchy and the democratically elected legislative Assembly. Although Kuwait is nominaly a constitutional monarchy, power is still firmly held by the emir, who has the power to appoint the Council of Ministers and push legislation through when he deems it necessary. The relationship between the executive and the legislative power is set out in the 1962 constitution, which created the Unicameral National Assembly. However, the National Assembly has increasingly begun to assert itself in recent years, and has slowed down various legislative reforms and often voiced strong criticism of the government. a) Executive branch Emir: The Emir is the head of state, and is chosen from among two alternating branches of the al-Sabah family. His authority is exercised through his chosen prime minister, traditionally the crown prince. Council of Ministers: The Council of Ministers (cabinet) is presided by the Prime Minister, usually the crown prince. The key ministerial positions in the cabinet are usually given to other important members of the royal family, with lower ranking ministers increasingly appearing from the ranks of the elected National Assembly. b) Legislative branch National Assembly (Majlis al Umma): The Assembly consists of 50 elected members, in addition to the ministers (ex officio members of the Parliament), who serve for a term of four years. Voting rights are currently reserved exclusively for men who are over the age of 21 and are of Kuwaiti nationality by right. However, a decision taken by Emir Jaber alSabah in May 1999 allowed women to vote and stand as candidates in parliamentary and municipal elections as from 2003, a decision which needs Parliament's approval to come into force. c) Judiciary Civil law system with elements of Islamic law. d) Regional Administration Local administration is carried out in five principalities – Kuwait City, Hawalli, Jahra, Farwaniya, and Ahmadi – each of which has its own governor. 4 2.2. Key political players Formal political parties are illegal, with deputies sitting as independents - although informal groupings do exist. These include the Islamic Constitutional Movement, the Islamic Popular Grouping, the Shi'a group, two Sunni Islamic and some traditionalist groups, a group of independents close to the al-Sabah, and a secular group known as the Kuwaiti Democratic Forum. HH Sheikh Jaber al-Ahmed al-Jaber al-Sabah became Emir in 1977, after serving as the first Finance Minister of the state from 1949 and, later, as a Prime Minister. As such, he has been the centre of power in the rapid oil-led development Kuwait. The Sheikh has been reluctant to share his power. In 1986, he dissolved the National Assembly, reinstating it in 1992 under pressure from Western powers after the Gulf War, only to dissolve it again in 1999 when relations between the government and parliament had become tense. Iraq's invasion of Kuwait severely damaged public respect for the Emir and the ruling family, who were blamed for lack of preparation in threat of war. He has now handed much of the day-to-day running of the state over to the Crown Prince, partly due to his ill health. The Crown Prince and Prime Minister: HH Aheikh Saad al-Abdullah al-Salem al-Sabah was able to resume most of his responsibilities in 1998, after a period of seven months spent out of the country in 1997 to receive medical treatment. According to observers, he has been a cautious Prime Minister, unwilling to commit himself to unpopular and controversial decisions that would bring him into conflict with the National Assembly. This has helped him preserve his popularity among Kuwaitis, but has prevented the implementation of essential reforms necessary to reduce oil dependency and welfare spending. Sheikh Saad has come under increasing pressure to resign, due to his bad health. The Foreign Minister and First Deputy Prime Minister is Sheikh al-Ahmed al-Jaber alSabah's. His relations with the Crown Prince are stormy, and he has tendered his resignation on several occasions. During Sheikh Saad's illness, he acted as a Prime Minister. Sabah is said to be particularly unhappy with the lack of progress in economic reforms and the slow pace of reconciliation with the Arab countries that voiced support for Iraq during the Gulf War. Sheikh Jaber Mubarak al-Sabah was appointed Deputy Premier and Defence Minister in February 2001. He has been an advisor to the emir since 1992. Prior to this he held the Social Affairs Ministry in 1986 and was an Information Minister between 1988 and 1990. Deputy Premier and Interior Minister: Sheikh Mohammed Khaled al-Sabah retained his position in the new government, which was appointed in February 2001. Youssef Hamad al-Ibrahim, Finance and Planning Minister, is a leading liberal activist. He held the Education portfolio in the previous government. His appointment has been interpreted as a signal of governmental commitment to reforms. As a Finance Minister, al-Ibrahim will oversee the state-run Kuwaiti Investment Authority (KIA). Adel Khaled al-Subaih, the Oil Minister, previously held the Electricity portfolio and was a State Minister for Housing. A pro-Islamist, al-Subaih's appointment to the Oil Ministry in February 2001 is expected to soften opposition to proposals for the 5 development of the northern oil state fields by foreign companies. Al-Subaih has been a member of the Supreme Petroleum Council (SPC) since 1993. Ahmed al-Saadun is a controversial reforming democrat, re-elected as a Spokesman of the National Assembly in 1996 after a vote. He made a number of accusations of corruption against the government in 1998, and this undoubtedly played a role in precipitating the Emir's decision in May 1999 to dissolve parliament and call for early elections. Al-Saadun remained openly critical of what he considered to be government incompetence and mismanagement in the running of July 1999 elections, in which he easily retained his seat. Al-Saadun is one of 16 liberal MPs sitting in the parliament. 2.3. Developments and policy prospects Relations between the Parliament and the al-Sabah–dominated government were expected to improve after the 1996 elections, in which government candidates reversed the 1992 result. However, MPs continued to oppose measures affecting the subsidised lifestyle of their constituents, insisting that the government must reform its own administration first. Attacks on ministerial corruption and incompetence were common, particularly on the allocations of state contracts and the government’s failure to pursue charges against the former Oil Minister, Sheikh Ali Khalifa al-Sabah, and on missing funds from the Kuwait Oil Tankers Corporation. The case faces the problem of mixing political appointments with the ruling family and the perceived immunity of the al-Sabah family into sharp focus, and is one of the most contentious issues dividing the increasingly vocal parliament and appointed government. Perceptions of weakness and mismanagement in the heart of government were reinforced by the illness of Crown Prince/Prime Minister Sheikh Saad and his rivalry with his Deputy Prime Minister/Foreign Minister and probable successor, Sheikh Sabah. Sheikh Saad became the focus of criticism from MPs, the press and even some ruling family members who questioned his belief in democracy for Kuwait and the validity of his holding of two offices. The latter issues were of particular concern, given that Sheikh Saad's standing in the top echelons of the ruling family prevents him from being questioned by MPs in his role as a Prime Minister. 2.3.1. Last Elections (July 1999) A dispute between the parliament and the government arose in April 1999, when MPs accused the government of attempting to prevent them from questioning the Minister of Justice and Islamic Affairs, Ahmed Kleib, over a scandal concerning 120.000 misprinted copies of the Koran. When the entire cabinet threatened to resign in order to prevent a proposed no-confidence vote in Kleib by parliament, the Emir dissolved the assembly and called new elections for 3 July 1999. This action provoked outrage among opposition MPs. They accused the Emir of dissolving the Parliament in order to hide some potentially damaging allegations concerning the Finance Minister Sheikh Ali al-Salem alSabah. Although, political parties are illegal, loose groupings of candidates organised joint campaigns for the July 1999 elections. Opposition candidates accusing the government of organising a vote-buying operation in order to secure the election of a more compliant 6 parliament grouped under a banner "Political Forces". Their first action was to organise a fund to combat alleged government efforts to bribe the electorate in 15 strategic constituencies. Following an Emir’s decree, the government continued to exist in the interim period before members of the new Parliament were elected. It took advantage of the absence of opposition obstruction from the Parliament to pass a number of bills, in particular the setting up of a legal and financial committee, and in controversial areas such as tax and welfare reforms. In the past, MPs had been wary of passing such legislation, afraid of damaging their constituents' standard of living. A total of 287 male candidates contested the 3 July 1999 elections for the 50-seat National Assembly - the largest number of candidates since the 1991 elections. The opposition gained victory with a two-thirds majority, while the number of seats held by pro-government candidates was reduced to 14. The new Assembly is composed of 20 Islamists, 16 Liberals and 14 pro-government candidats. The opposition gained a clear two-thirds majority in the parliament, controlling only 21 seats in the last house. This majority puts both the liberals and Islamists in a strong position to block controversial legislation. Without doubt, the biggest winner in the polls was the liberal group, which previously held four seats. Among the liberal victors was the former Assembly Speaker, Ahmad al-Saadun, who had led much of the opposition to the government in the run-up elections, openly accusing the government of mismanagement and incompetence, and who had easily regained his seat. Les Islamistes, chiites et sunnites, sont donc devenus la force principale du Parlement, dont ils contrôlent 20 des 50 sièges. Les parlementaires islamistes sunnites ont créé un groupe qui, avec les islamistes chiites et d'autres personnalités, a condamné à la fois les attentats du 11 septembre 2001 et l'intervention américaine contre l'Afghanistan. Les Islamistes veulent étendre le rôle de la loi islamique, la Charia. Ils demandent depuis longtemps l'amendement de l'article 2 de la Constitution, qui affirme que la Charia est "une source principale de la législation". Pour eux, elle est "la source de la législation". Reste à savoir si le gouvernement et le palais sont prêts à accepter le jeu des élus en faisant du parlement un véritable instrument de contrôle de l'exécutif. 3. Foreign policy 3.1. International organizations Le Koweït est membre du Conseil de Coopération du Golfe, de la Ligue arabe, de l'Organisation de la Conférence islamique, de l'ONU et de l'OPEP. 3.2. Neighbouring countries The efforts of Kuwait to ensure its defence involve a twin strategy of building up its own armed forces and concluding defence agreements with its Western allies and Middle Eastern neighbours. Defence spending reached 30% of total government expenditure in 1996, with imports of high-technology equipment serving the dual purpose of upgrading the military capability of Kuwait and directly involving the US, France and the UK - the chief arms suppliers of Kuwait - in the defence of the country. However, its lack of 7 manpower - currently only 25 000 soldiers - and its lack of experience in using its complicated new military hardware limit the effectiveness of the Kuwaiti armed forces. The only realistic possibility of an overland attack seems to be for the north, where Kuwait has no natural line of defence and its oil facilities are near both Iran and Iraq. In early 1992, Kuwaiti officials disclosed plans to construct an electronic fence stretching more than 200 kilometres along the Kuwait-Iraq border. The main purpose of the fence is to prevent infiltration. Border guards of the Ministry of Interior of Kuwait are to patrol the fence area. a) Iraq March 2002 saw a somewhat unexpected thawing in relations between Kuwait and neighbouring Iraq. At the Arab Summit in Beirut, Iraqi Vice-President Ezzat Ibrahim announced that Iraq recognises the sovereignty and independence of the country that it had occupied in 1990. A deal was struck at the summit, under which Iraq promised it would not repeat its invasion of the oil-rich emirate. The sudden resumption of ties came against the backdrop of Arab opposition to the threat of US military strikes against Iraq, as well as widespread anger amongst the Arab nation at the Israeli army's incursions into Palestinian territories. Although developments at the Beirut summit represented for the first time that Iraq had pledged in writing not to repeat its 1990 invasion of Kuwait, it is very unlikely that full harmonisation of relations between the two countries will occur in the short term. The prevailing belief across the political spectrum of Kuwait is that Iraq remains a threat to the territorial integrity of the country, and the government of Kuwait opposed military attacks against Iraq on the grounds that such action would harm the Iraqi people and not the regime of Iraqi President Saddam Hussein. Kuwait can be expected to exercise pressure on Iraq to readmit UN weapons inspectors back into the country. Iraq had previously made hazy commitments to abandon claims against the country, but has continued to insist that Kuwait is part of Iraq. The kuwaiti government has sought to maintain international pressure on Saddam Hussein to comply with UN resolutions, recognise the sovereignty of the emirate and release the estimated 600 Kuwaiti prisoners of war still held in Iraq. The UK and the US remain firmly behind the sanctions imposed on Iraq in 1990. However, growing regional and international pressure to re-admit Iraq into the international community will force some form of normalisation of relations in the short to medium term. Kuwait will, therefore, have to decide whether to allow some form of conciliation with Iraq still led by Hussein, or continue to keep distance from its aggressive neighbour. b) Iran In contrast, relations with Iran have been improving steadily, particularly since the victory of the moderate Iranian President Khatemi in the 1997 elections. Military clashes between the two countries occurred during the Iran-Iraq war in the 1980s, when Kuwait was a major backer of the military effort of Iraq. During the last few years, a series of high-level visits between the two countries has led to growing ties between them, inspired, in part, by a mutual mistrust of Iraq. 8 c) Others arabic countries Kuwait has been slower to normalise relations with the countries that did not clearly oppose the Iraqi invasion in 1990, such as Yemen, Jordania and the Palestinian National Authority. This has been a matter of contention within the ruling family, as Foreign Minister Sheikh Sabah is seeking a more rapid rapprochement than the Emir and Crown prince have been willing to allow. In early 1998, a number of Jordanian prisoners were released in a unilateral gesture that may herald a Kuwaiti effort to restore diplomatic links. This was followed in September 1999 by a visit by Jordanian King Abdullah. The visit by a Jordanian monarch was the first of its kind for almost a decade. d) EUA L'émirat est encore traumatisé par l'invasion irakienne d'août 1990 et reconnaissant aux États-Unis et à leurs alliés de l'avoir libéré. Washington maintient des bases militaires au Koweït et vient d'y doubler le volume de ses stocks d'armement. 9 II. ECONOMIC SITUATION 1. Overview The economy is supported by its substantial oil reserves (oil and oil products account for 95 % of the country exports), together with investment income from considerable externally held foreign assets. These assets were secured by the past accumulation of sizeable current account surpluses, dating back to the oil price hikes of the 1970s. Given the relatively low "investment absorption" capacity of the country, the size of the financial assets are proportionately larger than other oil producers. The vast majority of citizens are dependent on public salaries paid for by government revenues from hydrocarbon exports, creating inflexible public expenditure commitments that are vulnerable to a decline in oil prices on the world markets. Attempts to reduce the budgetary burden have been limited, although a privatisation programme is now under way. The financial markets have recovered strongly from the damage caused by the Iraqi occupation of 1990-1991, which saw short term debts rise quickly to help finance considerable reconstruction, including in the banking sector, but these have since abated. La balance commerciale est redevenue excédentaire - 3 milliards de dollars - dès 1993 et, la même année, la balance de paiements a retrouvé l'équilibre. Le Koweït reste, donc, un État financièrement solide et, en dépit des gaspillages financiers, les autorités ont géré très prudemment les conséquences de l'occupation irakienne et l'effort de reconstruction. 2. Economic policy trends2 The huge rise in oil prices in 2000/2001 led to budget surplus in excess of US$5bn for a nine-month year (due to an alternation in the financial year start/end dates). The downturn in prices, while not approaching the troughs of 1998, will put more pressure on the government to reign in spending, as budgets become tighter. Kuwait boasts the third largest bourse in the Middle East in terms of market capitalisation (after Egypt and Saudi Arabia) - the Kuwait Stock Exchange (KSE) - but it has performed poorly in recent years. A number of significant reforms have been passed by parliament or are on the way. Restrictions on foreign investment and foreign ownership have been eased, the KSE will be opened to foreigners and legislation to open up the banking industry is planned. The free trade zone (FTZ) of Kuwait also continues to expand. However, plans to open the upstream oil sector to foreign companies have been slowed by a reluctant parliament. The government approved the creation of a new authority to oversee the economic reform programme of the country in April 2001 - the "Committee for development and economic reforms". The new body is to be headed by Foreign Minister Sheikh Sabah al-Ahead alSabah, and will be charged with overseeing the reform programme. The programme calls for gradual measures that will meet short and long- term targets set by the programme. Legal and administrative reforms had to be achieved by 2002, as they only required decisions to be made. Privatisation of a number of state-run companies was expected to 2 see Annex II, p. 17 10 be the main thrust of the reforms in combination with legal changes aimed at boosting private sector involvement. The fiscal position of Kuwait has been strengthened considerably by the rebound in oil prices over 2000/2001. The surge in oil prices - 55% higher for the year ending 31 March 2001 than the previous year - led to a healthy budget surplus of US$5,7bn. While Kuwait generally maintains a tight fiscal policy, a deficit was recorded in 1998 due almost entirely to plunging oil prices. With more than 80% of government revenue obtained from oil and oil product export receipts, the budget of Kuwait is highly dependent on international oil markets. With an estimated 93% of Kuwaitis employed directly by the government, or government owned industries, the government wage bill is the largest single government expenditure. Public services and subsidies also add to the government's spiralling spending burden. Beyond this, with more than 50% of GDP accounted for by state spending, Kuwait has a structurally unbalanced fiscal sector that will require reform now before it becomes a problem later. This reliance on oil and oil product exports means that the ability of Kuwait to plan strategic investment in the economy is limited. Although the government always forecasts a prudent oil price for the year ahead, the volatility of the market can lead to a huge surplus or deficit. Inflexibility over fiscal policy is becoming an increasing problem as the costs of maintaining public services and providing employment for nationals spirals due to a growing population, threatening to reduce the huge "nest-egg" of overseas investment. The level of government held foreign investments (some US$100bn) does provide some levelling of revenue when oil prices are depressed, but ultimately a modern taxation system and a diversified economy must emerge to provide the government with secure sources of revenue in the long term and allow more strategic planning for investment in the domestic economy. The country is perhaps (in proportional if not absolute terms) the most oil dependent economy in the region. The high oil income provides a source of revenue that could help fund a more diverse economy and the level of oil reserves mean that Kuwait will have high and secure export earnings for many years ahead. Equally there have been significant strides made towards economic and foreign investment liberalisation. The efforts of Kuwait to reform are dogged by conflicting influences. The government recognises the need to create a diverse economy and ease the financial burden on the state. However, the parliament is not keen to begin dismantling a generous state system that has taken decades to create, though the imperatives for doing so are seeping through gradually. 3. Economic growth The recovery of oil prices in 1999/2000 restored growth in Kuwait to a positive figure and pushed government revenue to record levels. The rapid return to fiscal health and towering growth rates had little to do with a still sluggish non-oil sector. Non-oil GDP is rising by approximately 1% a year, barely keeping ahead of inflation. Meanwhile, the more recent downturn in oil prices and production limits imposed by OPEC quotas means that the growth figures of Kuwait for 2000 and 2001 are unlikely to be matched over the next five years. Government attempts to liberalise the domestic economy and encourage foreign investment have been slow to develop, despite the acknowledgement of the 11 government that the medium-term health of the country depends upon it. The National Assembly is yet to fully come round to the thinking of the government on economic reform. The non-oil economy of Kuwait is dominated by overseas investments US$100bn worth of foreign investments generate the second largest source of GDP of the country, with an average annual return of around 10%. Non-oil GDP growth has been sporadic and precipitous. An 8,7% decline in non-oil GDP hit Kuwait in 1997 - before the oil price collapse. Non-oil growth has recovered from that low point, but despite the record rise in oil revenue through 2000, the non-oil sector has continued to lag. A number of reform measures were finally approved by the National Assembly in 2000/2001, but observers believe that bureaucratic inefficiency and state subsidies continue to hold back growth and must still be addressed. Banking and foreign investment reform - as well as a plan to attract foreign oil companies to the Kuwaiti oil sector - are now beginning to move. Friction between the National Assembly and government over ending subsidies, privatising state industries and allowing foreign oil companies still continues. Paradoxically, the steep falls in oil prices in late 2001/early 2002 have given the reform process more impetus, as the need for more non-oil revenue is once again brought to the fore. On the 10 July 2002, the Parliament passed the state budget for 2002-2003, with a deficit of US$6,26bn, up 32% from the previous fiscal year. The shortfall has raised tension in the legislative assembly, which has in recent months been rocked by a failed attempt by Islamist opposition groups to oust Finance Minister Yussif al-Ibrahim. 4. Employment and wages The state currently employs the vast majority of the 212 000 working nationals, with citizens guaranteed a public sector job. Some observers maintain that many are effectively underemployed, being paid salaries for jobs that do not exist. With a youthful population adding 14 000 to the labour market every year, the government has increasingly struggled to cope with the demand for jobs - particularly as the level of education and career expectations has risen. The wage bill now accounts for more than half state revenues of US$7,3bn. In the private sector, some 5% of the work force are Kuwaitis - the rest are made up of foreign workers. The government has begun to address this problem by imposing regulations to encourage the employment of nationals and penalise the employment of foreigners. Kuwait still relies upon expatriate workers to fill a number of technical roles. Efforts to train Kuwaitis to assume management roles in the utilities and to train more technical staff receive a high priority. Unemployment is a growing problem and the government will need to reduce the employment and wage expectations of many Kuwaitis as higher unemployment looms. Public-sector workers use the threat of strikes to back up their wage and benefit demands. Kuwait is a welfare state and heavily subsidises many social needs. The social sector of course was heavily damaged during the Iraqi occupation but strenuous efforts are underway to get the welfare system back to where it was on 1 August 1990. 12 5. External sector and attitudes towards foreign investment In the 1950s and 1960s, Kuwait began investing overseas in property and businesses in Britain. In 1952 Kuwait established an office in London, staffed with experienced British investment counsellors who guided the government's placement of funds. In the same year, Kuwait created investment relations with a large New York bank. Because of the vastly expanded oil revenues of the 1970s, the overseas investment program of Kuwait grew tremendously. In 1976 the government established the Reserve Fund for Future Generations, into which it placed an initial US$7 billion. It decided to invest 10 percent of its revenues annually in the reserve fund. Money from the fund, along with other government revenues, was invested in overseas property and industry. In the 1970s, most of these funds were invested in the United States and in Western Europe: in German firms (such as Hoechst and Daimler Benz, in each of which Kuwait owned 25 percent), in property, and in many United States Fortune Five Hundred firms. In the 1980s, Kuwait began diversifying its overseas investments, placing more investments in Japanese firms. By the late 1980s, Kuwait was earning more from these overseas investments than it was from the direct sale of oil: in 1987 foreign investments generated US$6,3 billion, oil US$5,4 billion. The Financial Times of London estimated the overseas investments of Kuwait in early 1990 at more than US$100 billion, most of it in the Reserve Fund for Future Generations. The Iraqi invasion proved the importance of these investment revenues. With oil revenues suspended, the government and population in exile relied exclusively on investment revenues, including sales of investments for sustenance, for their share of ongoing coalition expenses and for post-war reconstruction and repair of the vital oil industry. Kuwait is receptive to foreign investment in those areas of the economy not dominated by the public sector. There are no foreign-exchange controls, and profits, capital gains and royalties are all freely transferable in and out of the country. However, at present, nonKuwaiti investors are subject to taxation of profits. Foreign ownership of real estate is not - apart from a few exceptions - permitted. Foreign firms may only tender for government contracts that are specified for international bidding. Kuwait took several steps forward in attracting more foreign investments during 2001. A new package of foreign investment incentives was passed by Parliament and a draft bill to reduce taxes on foreign companies was approved by Parliament. A number of difficulties still have to be addressed, but the government is slowly moving forward in its efforts to improve the climate for foreign companies in Kuwait. In May 2000, Parliament voted in favour of allowing non-Gulf Co-operation Council (GCC) foreigners to hold shares in the Kuwait Stock Exchange (KSE). There are 90 companies listed on the KSE, with market capitalisation at some US$20bn. Investors have also been encouraged by reform measures to increase transparency on the bourse and curb inside trading and volatility. The challenge for Kuwait is not simply one of changing the economic structure, foreign investment regulations and the legal and business environment, but also one of competing with the increasingly aggressive GCC neighbours. Dubai and Bahrain have been quick to open up their economies to tourism, finance and trade. They have geographic advantages (better for trading with Iran and international markets, for example) and more liberal 13 religious regimes. Kuwait will not simply have to equal these competitors in economic liberalisation, but surpass them if the economy of the country is to become more diversified. The country attempts to encourage telecommunications and light industry through the Kuwait Free Trade Zone (KFTZ), established in 1996. The latest efforts of Kuwait are aimed at establishing itself as the leading country in the region for telecommunications. In this it is again up against Dubai, which is itself well advanced in efforts to attract telecom companies. For Kuwait, non-oil economic sectors are more potential than established. 14 III. RELATIONS ENTRE L’UNION EUROPÉENNE ET LE KOWEÏT3 1. Contexte politique Il n'y a pas de véritables relations bilatérales entre l'Union européenne (UE) et le Koweït Cependant une coopération existe: elle s'inscrit dans le cadre des relations entre le Conseil de Coopération du Golfe (CCG) et l'UE. En effet, en 1989, la Communauté européenne et le CCG ont conclu un accord de coopération qui prévoit, entre autres, une rencontre annuelle des ministres des Affaires étrangères. Les objectifs affichés de cet accord est de promouvoir les relations commerciales, ainsi que de renforcer la sécurité dans la zone stratégique que constitue le Golfe. Des groupes de travail ont été établis dans les domaines de la coopération industrielle, de l'énergie et de l'environnement. En 1996, la mise en place d'une coopération décentralisée (coopération universitaire, coopération dans les domaines des affaires et des médias) a été prévue. L'accord de coopération de 1989 prévoit aussi un engagement des deux parties d'entrer en négociation pour la conclusion d'un accord de libre-échange entre le CCG et l'UE. La condition préalable à la conclusion de cet accord est l'établissement d'une union douanière parmi les pays membres du CCG. L'Union douanière devrait être en place au 1er janvier 2003. La douzième rencontre ministérielle dans le cadre de la coopération UE-CCG a eu lieu à Grenade, en Espagne, le 28 février 2002. Lors de cette rencontre, a été réaffirmé l'idée selon laquelle le commerce, les investissements et la coopération constituent les bases sur lesquelles on pourra développer les relations économiques entre les deux entités. L'UE a, par ailleurs, pris la décision d'envoyer une délégation à Riyadh courant 2002 afin de favoriser les relations avec les six pays du CCG. En outre, des points de vues communs ont été adoptés sur la situation internationale, concernant notamment la situation au Moyen Orient, l'Irak, l'Afghanistan et la lutte contre le terrorisme. 2. Relations commerciales La zone constituée par les pays membres du CCG représente le sixième plus important marché d'exportation de l'UE. De plus, l'UE a toujours eu un excédent commercial dans ses relations avec le CCG. Ainsi en 2000, le montant des importations de l'UE s'est élevé à 22 milliards d'euros, alors que le montant des exportations est chiffré à 29 milliards d'euros. Le pétrole brut représente presque deux tiers des importations de l'UE dans sa relation avec le CCG. Les exportations de l'UE vers les pays du CCG sont diversifiées, mais concernent principalement l'équipement de transport et la machinerie. L'UE exporte aussi des médicaments et des produits manufacturés. Les statistiques récentes montrent que les investissements de l'UE dans la région du Golfe ont nettement diminué. Ainsi, en 1999, l'UE avait investi pour 3 milliards d'euros, contre seulement 1,5 milliard d'euros en 2000. En revanche, les investissements des pays du CCG ont augmenté de plus de 15 % pendant la même période, passant de 4 milliards d'euros en 1999, à 4,6 milliards d'euros en 2000. 3 voir annexes III, IV et V, pp. 18-20 15 ANNEX I MAP OF KUWAIT 16 ANNEX II KUWAIT - ECONOMIC DATA (1) 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001 e 2002 f Domestic Data GDP Growth % Inflation % Budget Balance % GDP Leading Interest Rate % Unemployment Rate % GDP $ bn GDP Per Capita $ Interest Rate Spread, basis points 2,3 0,7 20 8,8 / 31,4 16532,8 30 2 0,1 15,3 8,9 / 25,2 12931,3 40 -2,4 3 -1,3 8,6 / 29,9 14764,6 25 3,5 2 28,6 7,3 / 40,4 19230,3 25 1,5 2,5 37,2 4,3 / 42 / 30 0 1,5 14,7 3,8 / 42,6 / 25 External Data Exchange Rate to $ Exports $m Exports Growth %. y-on-y Imports $m Imports Growth %.y-on-y Trade Balance $m Current Account Balance $m Current Account % GDP Reserves $m Reserves Import Cover- Months Foreign Direct Investment $m FDI % GDP Total External Debt $m Short Term Debt US$m Total Debt % GDP Total Debt Service Ratio % Total Debt % Exports Short Term Debt % Total Debt Short Term Debt % Reserves 0,3 14280,6 -4,5 -7746,9 -2,5 6533,7 7934,8 25,3 3556 5,5 19,8 0,1 / / / / / / / 0,3 9617,5 -32,7 -7714,4 -0,4 1903,2 2214,9 8,8 4052 6,3 59,1 0,2 / / / / / / / 0,3 12276 27,6 -6710 -13 5566 5062,2 16,9 4928 8,8 72,3 0,2 / / / / / / / 0,3 21700 76,8 -7620 13,6 14080 11200 27,7 7300 11,5 90 0,2 / / / / / / / 0,3 19500 -10,1 -8500 11,5 11000 8500 20,2 8000 11,3 100 0,2 / / / / / / / 0,3 16200 -16,9 -8700 2,4 7500 4100 9,6 8100 11,2 100 0,2 / / / / / / / (1) Source: IMF, World Bank 17 ANNEX III Trade relations EU-Kuwait: 2001 Structural analyses EU-imports (cif) 1000 € Total (A+B+C) of which: A: Raw materials Food, beverages and tobacco (0+1) Raw materials (2+4) Energy (3) B: Manufactured articles Chemicals (5) Machinery and transport eq. (7) Other manufactured products (6+8) -%- Main products (SITC division): SITC 3rd rev. 1000 € 2.380.465 100,0 PETROLEUM, PETROLEUM PRODUCTS AND RELATED MATERIALS 33 2.183.583 ORGANIC CHEMICALS 51 43.097 2.188.489 91,9 POWER GENERATING MACHINERY AND EQUIPMENT 71 31.437 503 0,0 OTHER TRANSPORT EQUIPMENT 79 27.060 4.403 0,2 PLASTICS IN PRIMARY FORMS 57 22.967 2.183.583 91,7 PROFESSIONAL, SCIENTIFIC + CONTROLLING INSTRUM. + APPARATUS, 87 N.E.S. 18.037 187.753 7,9 GENERAL INDUSTR. MACH. + EQUIPMENT, N.E.S., MACHINE PARTS, N.E.S. 74 9.617 67.092 2,8 MISCELLANEOUS MANUFACTURED ARTICLES, N.E.S. 89 6.981 87.914 3,7 TELECOMMUNIC. + SOUND RECORDING + REPROD. APPARATUS + EQUIPMENT 76 6.370 32.747 1,4 MACHINERY SPECIALIZED FOR PARTICULAR INDUSTRIES 72 5.849 % of total 91,7 1,8 1,3 1,1 1,0 0,8 0,4 0,3 0,3 0,2 Intraindustry trade intensity (1) 199,2 154,9 45,9 56,1 127,7 37,9 9,7 8,3 7,9 13,4 EU-exports (fob) 1000 € Total (A+B+C) of which: A: Raw materials Food, beverages and tobacco (0+1) Raw materials (2+4) Energy (3) B: Manufactured articles Chemicals (5) Machinery and transport eq. (7) Other manufactured products (6+8) Source: COMEXT 2 database, EUROSTAT -%- Main products (SITC division): SITC 3rd rev. 1000 € 2.749.092 100,0 ROAD VEHICLES (INCLUDING AIR-CUSHION VEHICLES) 78 377.203 ELECTR. MACH., APP. + APPLIANCES, N.E.S. + ELECTR. PARTS THEREOF 77 211.724 271.360 9,9 GENERAL INDUSTR. MACH. + EQUIPMENT, N.E.S., MACHINE PARTS, N.E.S. 74 189.409 239.668 8,7 MISCELLANEOUS MANUFACTURED ARTICLES, N.E.S. 89 161.876 21.276 0,8 TELECOMMUNIC. + SOUND RECORDING + REPROD. APPARATUS + EQUIPMENT 76 155.697 10.416 0,4 ARTICLES OF APPAREL AND CLOTHING ACCESSORIES 84 131.431 2.437.722 88,7 MEDICAL AND PHARMACEUTICAL PRODUCTS 54 108.430 290.003 10,5 POWER GENERATING MACHINERY AND EQUIPMENT 71 105.593 1.281.647 46,6 NON-METALLIC MINERAL MANUFACTURES, N.E.S. 66 96.960 866.072 31,5 MACHINERY SPECIALIZED FOR PARTICULAR INDUSTRIES 72 81.232 Production: JDa/Parliamentary Documentation Centre/European Parliament (1) The index can vary between 0 and 200: 0 means only exports, 200 only imports and 100 means balance in trade Index: (((x+m)-(x-m))/(x+m))*100 18 % of total 13,7 7,7 6,9 5,9 5,7 4,8 3,9 3,8 3,5 3,0 Intraindustry trade intensity (1) 0,9 3,9 9,7 8,3 7,9 2,3 0,1 45,9 0,6 13,4 ANNEX IV Trade of the EU with Kuwait by Member States EU-imports (cif) Total 2001 1000 € -%2.380.465 100,0 January-May: 2001 2002 (1) % change 1.086.704 720.136 -33,7 of which: France Netherlands Germany Italy United Kingdom Ireland Denmark Greece Portugal Spain Belgium Luxembourg Sweden Finland Austria 398.503 1.167.541 34.703 153.324 485.351 102 50.974 3.885 9.056 15.711 44.462 144 377 16.242 89 16,7 49,0 1,5 6,4 20,4 0,0 2,1 0,2 0,4 0,7 1,9 0,0 0,0 0,7 0,0 116.313 579.856 8.350 132.137 209.734 47 12.504 799 1 4.100 6.733 115 154 15.844 18 133.506 358.033 12.844 12.361 164.481 9 1.642 2.749.092 100,0 1.074.598 1.181.094 356.717 165.319 746.337 432.834 570.435 63.479 56.692 10.160 8.940 126.689 94.387 1.559 46.942 36.335 32.269 13,0 6,0 27,1 15,7 20,7 2,3 2,1 0,4 0,3 4,6 3,4 0,1 1,7 1,3 1,2 147.685 64.726 273.893 163.992 236.202 33.583 15.222 3.491 3.958 50.422 39.150 761 17.386 12.516 11.609 213.357 72.846 331.865 176.457 195.063 23.099 25.722 10.144 11.670 13.944 0 150 326 218 EU-exports (fob) Total of which: France Netherlands Germany Italy United Kingdom Ireland Denmark Greece Portugal Spain Belgium Luxembourg Sweden Finland Austria Source: COMEXT database, EUROSTAT Production: JDa/Parliamentary Documentation Centre/European Parliament (1) Total includes only January-February for Greece 19 4.125 52.061 27.194 531 14.861 27.407 15.328 9,9 ANNEX V Trade of the EU with Kuwait: 1995-2001 1000 ECU/€ EU-imports (cif) 1995 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001 Jan-May: 2001 Jan-May: 2002 Source: COMEXT database, EUROSTAT EU-exports (fob) 1.367.249 1.588.897 1.480.473 709.662 1.474.065 3.201.536 2.380.465 1.086.704 720.136 2.424.483 2.195.381 2.293.762 2.162.681 2.008.393 2.330.437 2.749.092 1.074.598 1.181.094 Balance 1.057.234 606.484 813.289 1.453.019 534.328 -871.099 368.627 -12.107 460.958 Production: JDa/Parliamentary Documentation Centre/European Parliament Trade of the EU with Kuwait: 1995-2001 3.500.000 3.000.000 2.500.000 1000ECU/€ 2.000.000 1.500.000 1.000.000 500.000 0 -500.000 -1.000.000 1995 1996 1997 EU-imports (cif) 1998 1999 EU-exports (fob) Production: JDa/PDC/EP 20 2000 Balance 2001 Jan-May: Jan-May: 2001 2002