Mental Health Awareness Week 2008 6

advertisement

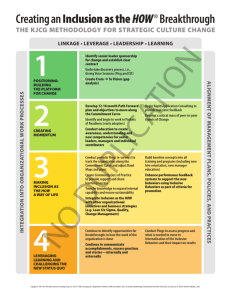

Mental Health Awareness Week 2008 6-12 October Make your mark for mental health Ko te tutukitanga, ka totoro, ka kawe kee, ka whakatau te manawanui ABOUT THE AUTHOR Ruth Gerzon is passionate about advocacy, human rights and social inclusion and community development. She has developed and facilitates training packages on health promotion and advocacy, and on social inclusion in the fields of mental health and disability. She lives in the Eastern bay of Plenty where she chairs a mental health/disability service working towards inclusion for all. She was executive officer for the Serious Fun ‘N Mind Trust, (BOP Like Minds, Like Mine Project) (1999-2003). She has also worked as an advocate, teacher (primary and tertiary), journalist and produced books and videos on rights and inclusion in the intellectual disability field. Her qualifications are: M.Phil (Social Policy, Massey 2003), Dip Tchng (Waikato Uni 1981) and Cert Journalism (Wellington Polytechnic 1971). She would welcome comments and critique of this article from readers interested in advancing social inclusion. She can be reached at ruthgerzon@gmail.com. Social Inclusion By Ruth Gerzon Social inclusion has become widely acknowledged as vital to mental wellbeing yet its exact nature is often unexamined, and mental health services do little to support people to overcome their isolation and exclusion. People without close family ties leave hospitals for residential services, then graduate to ‘independent living’. This move may be heralded a success, but in reality people in flats and boarding houses are often lonely. Unable to make the transition from roles as passive patients to active roles in communities, they have little sense of purpose or belonging. Isolated and marginalized, many become unwell again, re-entering acute care. 1 Communities are sometimes the problem. In spite of the Like Minds, Like Mine project, they are far from being giant shopping malls of great experiences awaiting intrepid explorers. Yet our community mental health services also need to change if social inclusion is to become a reality. Most services still focus on what is wrong with people. Someone entering a mental health service may have decades of success as a parent, worker, volunteer or sportsperson. All this is discarded when they walk through a hospital door to become a ‘patient’. Their skills and achievements are not noted on their files, nor form a basis for connection with the people they encounter in this new world. Welcome to a new life as a passive recipient of care, where your past is all but irrelevant. This world is underpinned by unequal relationships. Staff are paid to meet your needs; your only role is as ‘patient’. For short periods we all need this level of support, but for some people entering mental health services this new world and their new role becomes their life, one they may never leave behind. In this world a whole bunch of rules apply. ‘Patients’, ‘residents’, ‘clients’ or ‘service users’ learn not to have expectations about privacy, individuality or confidentiality. They learn about conformity, compliance and dependency. Dr Patricia Deegan has noted that, “becoming a ‘good’ mental patient often means learning to become preoccupied with matters pertaining to ‘me’….Socialization into meness, self-preoccupation and being a consumer means that many people are denied the opportunity to discover they have something to offer to other people.”1 Recovery stories show that self-preoccupation is not healthy. Both contribution to others lives and mutual relationships are vital ingredients in recovery. People need to feel again the basic goodness of life and gain self-respect to make progress towards mental health. Yet, as Davidson et al note (2001)2, most ‘community based’ services still require people to succeed before they are ‘let in’ and continue to focus on illness, ignoring people’s gifts and capacities. As soon as people leave hospital for community care, the real world, the inclusive world needs to regain its central place in their lives. In this world people have something to offer. Everyone plays active roles, contributing to communities through paid and voluntary work, as part of sports clubs or arts. These roles bring a sense of purpose and belonging and full citizenship. People’s illness impacts on their self-esteem, so they often cannot re-connect with communities where stigma is still rife, without support. Services need to change and support people to take these essential steps to wellbeing. 1 Deegan, Patricia, 2003, http://www.patdeegan.com/blog/archives/000015.php (22.8.08) Davidson L, Stayner D A, Styron T H, Nickou, C, (Spring 2001) “Simply to be let in”: inclusion as a basis for recovery Psychiatric Rehabilition Journal, Boston in MHC (2001) Book of Collected Articles: a companion to the Mental Health Recovery Competencies Teaching Resource Kit 2 2 The first change needs to be in their fundamental orientation. If their only relationship is with service users they will continue to keep people dependent. services service users passive recipients of care To enable people to gain citizenship through active roles in their communities of choice there needs to be another focus: communities contribution citizenship mutual relationships passive recipients of care services service users Re-oriented to this third dimension, services will explore communities and deepen their knowledge of their functions. They will find that there is no one ‘community’, but diverse ones, in many shapes, sizes and dimensions. These may be based on ethnicity, on shared experiences, identities, beliefs, interests, neighbourhoods or the internet. We all feel more welcome in some communities than others: no one is comfortable in all contexts. Many of us play active roles in two or more. Maori communities – whanau and hapu – are based on mutual support. This gives them strength. Seeking similar support systems, settler communities of migrants far from their extended families, set up a multitude of voluntary associations so people new to a town could make connections. The essential building blocks of all these communities are reciprocal, equal relationships, where people help one another, the very opposite of relationships on which services are based. Such mutual relationships engender three elements essential to mental health: a sense of belonging, a sense of purpose and selfrespect. Contrast this understanding of contribution and relationships in diverse communities with some ‘community participation’ or ‘meaningful activity’ programmes. Their narrow focus often resembles ‘community tourism’. Like tourists, people are encouraged to use banks and shops, beaches and parks. These are places of commerce and relaxation, not of connection. In these places people cannot contribute their gifts, nor build the mutual relationships that underpin rich social networks. 3 ‘Social capital’ is a term often used for the mutual relationships and trust that underpin communities. Social theorist, Robert Putnam3 sees social capital as benefitting people in two ways. The first is ‘bonding’, which is crucial for just getting by, for making sure there will be someone there for us when times get tough. Without this, when we need support, we fall back on services. Sadly some people with mental illness have become so disconnected from families and communities that the only people in their lives are those paid to be there. ‘Bonding’ social capital is evident in extended families, ethnic organizations, netball teams and, within the mental health field, in some peer support groups. Peer support groups that focus on mutual support and reject the mainstream medical model of relationships based on helper’ and ‘helped’, can rebuild self-esteem and pave the way for people to take up mutual relationships in their wider communities. The second form of social capital Putnam termed ‘bridging’. Where bonding helps us get by, bridging social capital helps us get ahead, finding work, linking us to resources and providing information. Many of us have found work or somewhere to live through our networks. Service clubs are a good example of bridging social capital. Both forms of social capital are important for people with experience of mental illness. Bonding enables people to find support beyond services. Bridging enables them to find new valued roles and to access resources. Over the past three decades some sociologists have noted a weakening of social capital. Club membership is declining, sports coaches are hard to find and young people are less active in communities than their elders. Unlike our grandparents we often buy in support services once provided by neighbours: lawn mowing, child or elder care. Putnam attributes some of this decline in social capital to increased viewing of television, making us passive and individualist and encouraging materialism. Yet there are signs of new neighbourhood initiatives, such as restoration of wetlands and collective actions to reduce violence. Perhaps the increased use of buses and car pooling will enable us to connect while commuting. Climate change may even have a positive effect on social capital, as communities came together during the war years. If Putnam is right the decline in social capital is outside the control of mental health services. Of more concern is the view of John McKnight4, who sees services themselves as the culprits. He believes the professionalization of care (elder care, child care, health care) is directly responsible for reducing communities’ capacity for looking after their own. Reflecting on McKnight’s thesis, a colleague, Hine Tihi, noted how community support for people with a disability weakened in a small town after a kaupapa Maori service was 3 Putnam, Robert J, (2000) Bowling Alone: The Collapse and Revival of American Community, Simon and Schuster Paperbacks, New York 4 McKnight, John (1995). The Careless Society: Community and Its Counterfeits. United States: Basic Books. 4 set up. Before the service opened, when someone in the wharekai needed help, everyone would chip in. Afterwards some whanau began to respond with “your caregiver is over there…”. As professional carers move in the community backs off. In the Like Minds, Like Mine advertisements featuring Aubrey Quinn, we see him supported by his rich social networks. Is the need for such advertisements caused not only by stigma but also by the professionalisation of care that leaves us keen to back off from friends when the going gets tough, and refer them instead to social services? We need to be mindful of the inherent contradiction between our insistence on a well trained workforce and the central message of the Like Minds, Like Mine advertisements. If social inclusion is vital to mental health, how can mental health services re-connect isolated people to their communities of choice? Existing services can turn to the model developed by supported employment. These services help people use their gifts and capacities to find work. Sadly supported employment is still not widely available and only deals with one aspect of people’s lives: paid work. People with good mental health are connected to their communities through many channels. I believe everyone has strengths and gifts, everyone can contribute to their communities. This is the basis on which people can be supported to gain valued roles. Real progress on inclusion will happen when these gifts and strengths are given more prominence than symptoms of illness. Staff need to know how communities function and reciprocal relationships form, they need the skills to support people to use their strengths in community settings, while taking care to reduce the likelihood of rejection due to stigma. We cannot ensure people have friends but we can put them in a situation in which ‘bonding’ develops, enabling them to spend time in valued roles, in communities. These roles can be in paid or voluntary work, on marae, and in towns, as club members, in political or environmental activities, through crafts or art. If we are serious about social inclusion some aspects of our current services that might need to change are: Training: Do staff know how communities function? Do they have the skills to help people build reciprocal relationships? Do we need to re-orient training to focus on practical aspects of inclusion? Recruitment: Do we value people’s community networks and take them into account? Information: Do we gather information on community networks and organisations? Rosters: Do staff have one-to-one time? Supporting people to contribute to communities and build relationships doesn’t happen in groups. Job descriptions and titles: Do these still focus on ‘support’? Might staff be called ‘community connectors’? When setting up or funding new services: Are we sure services are part of the solution not part of the problem? 5 From their own experiences readers will see other aspects of services that might need to change to focus on social inclusion. Change will be far reaching, mostly uncharted and exciting. . It will need innovative and courageous leaders who believe all people can contribute to communities and build the mutual relationships that bring good mental health. 6