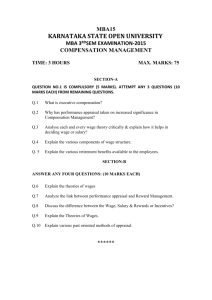

Minimum wages as a soft standard in the informal

advertisement