chapter overview

advertisement

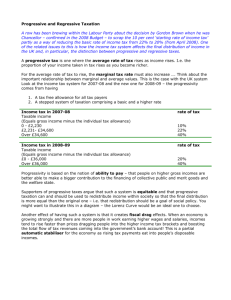

Public Choice Theory and the Economics of Taxation CHAPTER TWENTY-SIX PUBLIC CHOICE THEORY AND THE ECONOMICS OF TAXATION CHAPTER OVERVIEW This chapter includes a study of public choice theory, an economic analysis of government decision making, and selected topics related to public expenditures and tax revenues. The theoretical discussion includes an examination of the inefficiency of voting outcomes, interest-group influence, political logrolling, and the paradox of voting outcomes. Also examined is public sector failure, or the failure of public decisions to promote the general welfare. Attention is then focused on how public goods are financed. The ability-to-pay vs. the benefits-received principles of taxation are evaluated. Progressive, proportional, and regressive taxes are defined and illustrated with examples. The concepts of tax incidence and efficiency loss are also reviewed. This chapter concludes with a discussion of the structure of the U.S. tax system. INSTRUCTIONAL OBJECTIVES After completing this chapter, students should be able to: 1. Explain the problems created by government intervention in the market. 2. State four reasons given by conservatives and libertarians for government’s inefficiency in providing goods and services. 3. Identify categories of government spending: Expenditures, Transfer Payments, and Subsidies. 4. Differentiate between the benefits-received and ability-to-pay principles of taxation. 5. Identify which taxes are progressive, proportional, and regressive. 6. Identify the incidence of the personal income tax, corporate income tax, sales and excise taxes, and property tax. 7. Explain the U.S. structure relative to the progressive or regressive nature of Federal, state, and local taxes. 8. Define and identify the terms and concepts listed at end of the chapter. LECTURE NOTES I. Introduction A. Learning objectives 1. The difficulties of government intervention in the free market. 2. About “government failure” and why it occurs. 3. The different methods of distributing a nation’s tax burden. 4. The principles relating to tax incidence, and efficiency losses from taxes. B. In the last chapter we examined some examples of market failure in the private sector and the government policies designed to remedy them. This chapter examines more closely the public sector and its failures that elicit disenchantment. 436 Public Choice Theory and the Economics of Taxation C. This chapter deals with two main topics: a. “Public choice theory” is the economic analysis of government decision-making that helps us to understand public sector problems. b. The economics of taxation. II. Government failure can occur as well as market or private sector failure. The fact that the latter exist does not mean that the public sector improves efficiency. A. SPECIAL INTEREST EFFECT: promotes the interests of a small group at the expense of society at large. 1. The special-interest effect refers to the situation where a small number of people will receive large gains at the expense of a much larger number of people who individually suffer small losses. The small group will be well informed and highly vocal on the issue and press politicians for approval. The large numbers who will each suffer small losses will not have the incentive to be informed or feel strongly. The result is that the politician will support the special-interest program, whose supporters will notice the vote in their favor, and ignore the majority who don’t feel strongly. 2. Pork-barrel politics and Earmark spending is an example of the special-interest effect. In this case, the benefit goes to a single political district and to the politician from that political district. The cost of the project is spread out to many individuals who will never receive the benefits. Pork-barrel politics is often combined with logrolling. Logrolling or vote trading may also secure favorable decisions for those who feel strongly about certain issues B. RENT-SEEKING: behavior occurs when a transfer of wealth at someone else’s or society’s expense occurs through government action. Here the term “rent” means any payment to a resource supplier, business, or other organization above that which would accrue under competitive market conditions. Examples include tax loopholes that benefit only certain groups; public works projects that cost more than the benefits they yield; and occupational licensing that requires more than is necessary to protect consumers. C. SHORT-SIGHTED BEHAVIOR: Clear benefits, hidden costs (or the reverse, immediate costs and future more vague benefits) are another dilemma for politicians trying to decide on public programs. Where the benefits are recognizable and popular, the politician may vote for the program even if the costs exceed these benefits if the costs are diffuse or hidden. D. RATIONAL IGNORANCE: Recognizing that their vote is unlikely to be decisive, most voters have little incentive to obtain information on issues and alternative candidates. E. REGULATORY CAPTURE: Bureaucracy and inefficiency can be another problem in the public sector because there is not the profit motive or competitive pressure to perform efficiently. Ironically, the typical response of government to a program’s failure may be to increase its budget and staff. 1. Government employees, together with the special-interest groups they serve, often have the political clout to block attempts to pare down or eliminate their agencies. 2. There is a tendency for government bureaucracy to justify continued employment by looking for and eventually finding new problems to solve. E. Imperfect institutions exist in both the public and private sectors, which often makes it difficult to decide which institutions would perform best in the production of certain goods and services. 437 Public Choice Theory and the Economics of Taxation III. Government Spending A. Expenditures: Government Spends Money to purchase products and resources, and redistributes money to correct externalities and resolve inequity. a. Expenditures: government spending to purchase real goods and services in the product and resource markets. b. Transfer Payments: redistribution of income to households such as welfare, social security, medicare and other social programs. c. Subsidies: payments to businesses to encourage production of public goods and other goods with public or external benefits—safe cars, farm products, medicine. IV. Apportioning the tax burden and deciding how the public sector should be financed is also a complex question. A. Benefits received vs. ability to pay principle of taxation. 1. The benefits-received principle asserts that households and businesses should be taxed in relationship to the services they receive. For example, gasoline taxes are earmarked for highway construction and maintenance. a. How can the government decide which citizens receive how much benefit from less divisible public goods like national defense? b. Government efforts to redistribute income would be self-defeating if the benefits-received principle of taxation were applied universally—welfare recipients would have to pay for their welfare at the extreme version of this. 2. The ability-to-pay principle asserts that the tax burden should rest more heavily on those with greater income and wealth. The rationale is that those people with much income or wealth will value their marginal dollars less than those with low incomes, where each dollar is very meaningful. B. Progressive, proportional, and regressive taxation systems relate to the above issues 1. A tax is progressive if its average rate increases as income increases; the tax grows absolutely with income and also proportionately. 438 Public Choice Theory and the Economics of Taxation 2. A tax is proportional if its average rate remains the same; the tax payment grows absolutely in dollar amount with income but remains the same proportionate to income. 3. A tax is regressive if its average rate declines as income increases; the tax may or may not increase in the absolute amount, but it declines in proportion to income. B. Tax Base 1. Federal Government receives the majority of its money from Personal Income taxes and payroll taxes such as social security. The federal government had to pass a Constitutional amendment to establish the income tax. 2. State governments receive most of their revenue from sales taxes and personal income taxes. 3. County and City governments receive most their funding from property taxes. C. Applications in existing tax structure: 1. The federal personal income tax is mildly progressive, with marginal tax rates ranging from 10 to 35 percent. Certain deductions that favor high-income groups erode the progressivity of this tax. 2. Sales taxes are not as proportional as they seem if they are on all goods. A general sales tax is regressive because, although everyone pays the same percent on expenditures, the rich tend to spend a much smaller fraction of their incomes, while the poor may spend all of their incomes. Therefore, the rich will pay a smaller overall proportion of their income in sales taxes. 3. Payroll taxes are regressive. The Social Security portion of the tax (6.2 percent) is not applied to income above a certain level ($94,200 in 2006). On the other hand, the Medicare tax (1.45 percent) is applied to all wage income. A person making $94,200 pays 7.65 percent ($7206) of his or her wage income; a person making $188,400 pays only 4.55 percent ($8572) of his or her wage income. 4. Property taxes tend to be regressive because landlords pass along this cost to tenants who have lower incomes; housing costs are a larger proportion of income for the poor than for the rich, so economists estimate that the property tax on that housing would end up being a greater proportion of low incomes than of high incomes. V. Tax Incidence and Efficiency Loss A. Every tax transfers money from private choices to public choices. Friedman calls the loss of freedom of choice from taxes ‘Deadweight Loss’. B. Tax incidence refers to who actually bears the economic burden of a tax. 1. The division of the burden is not obvious. 3. In this example, consumers and producers may share the burden of the tax equally or the producer may pass on the entire tax amount to the consumer. C. Probable incidence of U.S. taxes is estimated for various taxes. 1. The personal income tax generally falls on the individual except for those who can control the price of their labor services and pass on the cost of the tax through higher fees. 2. The incidence of the corporate income tax is uncertain. Some corporations may be able to shift the burden by charging higher prices; others may find there is decreased profitability and the burden is then borne by stockholders. 439 Public Choice Theory and the Economics of Taxation 3. Sales taxes cover such a wide range of products, the incidence of sales taxes is most likely to fall on the buyer. 4. The incidence of property taxes may fall on the property owner, or in the case of rental and business property, the tax would be largely shifted onto the tenant or the customer. VI. The U.S. Tax Structure A. It is difficult to determine whether the overall American tax system is progressive or regressive. Disagreement among economists persists. B. The Federal tax system: The system is progressive. 1. In 2004, the average Federal tax rate for the 20 percent of taxpayers with the lowest incomes was only 5.2 percent. The tax rate for the 20 percent of the taxpayers with the highest income was 23.8 percent. The tax rate was 24.9 percent for the top 10 percent of tax payers and 26.7 percent for the top 1 percent. 2. This progressivity is offset by the Social Security tax, which is regressive. Because of the cap of $94,200, taxpayers who earn more, pay a lower percent of their income as tax than do lower and middle income earners. C. The state and local tax system: State and local tax structures are largely regressive as a percentage of income. Both sales and property taxes fall as a proportion of income when income rises. D. Combined Tax Structure: Overall, the American tax structure is slightly progressive. The American system of taxes and transfer payments does reduce income inequality and is estimated to quadruple the incomes of the poorest one-fifth, which makes the tax-transfer system more progressive than the tax system alone. 440