Sino-American Relations - SCUSA 63 - Final

advertisement

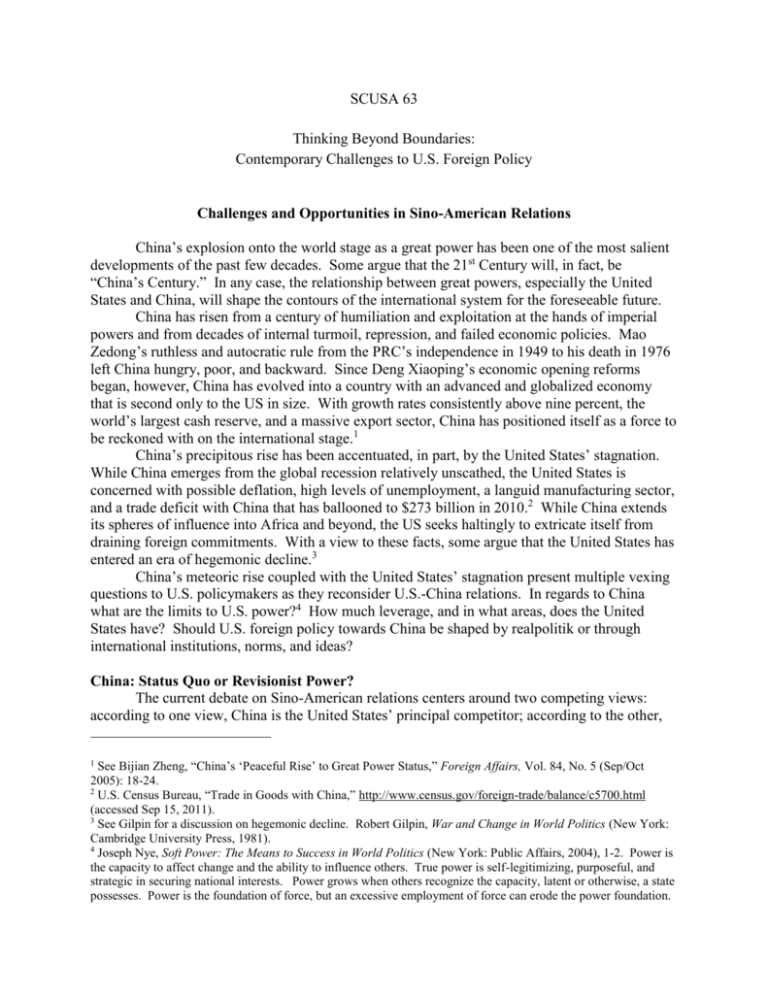

SCUSA 63 Thinking Beyond Boundaries: Contemporary Challenges to U.S. Foreign Policy Challenges and Opportunities in Sino-American Relations China’s explosion onto the world stage as a great power has been one of the most salient developments of the past few decades. Some argue that the 21st Century will, in fact, be “China’s Century.” In any case, the relationship between great powers, especially the United States and China, will shape the contours of the international system for the foreseeable future. China has risen from a century of humiliation and exploitation at the hands of imperial powers and from decades of internal turmoil, repression, and failed economic policies. Mao Zedong’s ruthless and autocratic rule from the PRC’s independence in 1949 to his death in 1976 left China hungry, poor, and backward. Since Deng Xiaoping’s economic opening reforms began, however, China has evolved into a country with an advanced and globalized economy that is second only to the US in size. With growth rates consistently above nine percent, the world’s largest cash reserve, and a massive export sector, China has positioned itself as a force to be reckoned with on the international stage.1 China’s precipitous rise has been accentuated, in part, by the United States’ stagnation. While China emerges from the global recession relatively unscathed, the United States is concerned with possible deflation, high levels of unemployment, a languid manufacturing sector, and a trade deficit with China that has ballooned to $273 billion in 2010.2 While China extends its spheres of influence into Africa and beyond, the US seeks haltingly to extricate itself from draining foreign commitments. With a view to these facts, some argue that the United States has entered an era of hegemonic decline.3 China’s meteoric rise coupled with the United States’ stagnation present multiple vexing questions to U.S. policymakers as they reconsider U.S.-China relations. In regards to China what are the limits to U.S. power?4 How much leverage, and in what areas, does the United States have? Should U.S. foreign policy towards China be shaped by realpolitik or through international institutions, norms, and ideas? China: Status Quo or Revisionist Power? The current debate on Sino-American relations centers around two competing views: according to one view, China is the United States’ principal competitor; according to the other, See Bijian Zheng, “China’s ‘Peaceful Rise’ to Great Power Status,” Foreign Affairs, Vol. 84, No. 5 (Sep/Oct 2005): 18-24. 2 U.S. Census Bureau, “Trade in Goods with China,” http://www.census.gov/foreign-trade/balance/c5700.html (accessed Sep 15, 2011). 3 See Gilpin for a discussion on hegemonic decline. Robert Gilpin, War and Change in World Politics (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1981). 4 Joseph Nye, Soft Power: The Means to Success in World Politics (New York: Public Affairs, 2004), 1-2. Power is the capacity to affect change and the ability to influence others. True power is self-legitimizing, purposeful, and strategic in securing national interests. Power grows when others recognize the capacity, latent or otherwise, a state possesses. Power is the foundation of force, but an excessive employment of force can erode the power foundation. 1 2 China is the United States’ principal partner in solving increasingly complex problems that require multilateral responses. Which of these views is correct depends in large part on China rather than the United States. In the anarchic system characterized by uncertainty among states, U.S. policymakers must craft foreign policy based on their assessment of China’s aspirations and strategy. China may be content to follow a strategy by which they accept the West’s international institutions, or it may reject the Western-dominated international system altogether. China’s acceptance into the World Trade Organization, increased participation in regional organizations, deployments to neighboring states to assist with humanitarian disasters, and its participation in policing the waters off the Horn of Africa are examples of the former; China’s call for a new international currency to replace the dollar is an example of the latter.5 Will China seek regional hegemony or will it reach some mutually-satisfactory powersharing arrangement with the United States? Defining China as a status-quo or revisionist power is useful in that it may illuminate the prospects for conflict or cooperation in this relationship.6 This, in turn, will help us best prescribe appropriate policies to fit our economic, military, and political strategies. If the U.S. and China are in a spiral environment, perhaps the United States should pursue “positive-sum” policies that incentivize mutual trust, transparency, and economic ties in order to minimize the likelihood of internecine conflict. On the other hand, if the U.S. and China exist in a deterrence environment, maybe the U.S. should pursue a “zero-sum” strategy which views any relative increase in Chinese power as a long-term threat to the national security and economic interest of the U.S.7 A third alternative might envision a hedging strategy as a combination of the two. Another critical question policymakers must ask is: What drives China’s and other Southeast Asian states’ balancing behavior? Will states balance when there is a shift in power or threat? Moreover, will Southeast Asian states balance against the greatest power in the region for security, or will they bandwagon with the greatest power in the region for profit? International and Domestic Constraints Both the United States and China operate under unique international and domestic imperatives that cannot be ignored in assessing the prospects for their bilateral relationship. The two-level game faced by leaders from both states constrains their freedom of action in important ways. On the international level, the leadership of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) is supremely concerned with the “twin goals of security and great power status” in the international arena.8 On the first matter, China has benefitted from a relatively benign environment over the last thirty years. China has settled many of its decades-old border disputes with Russia, Vietnam, and others; it has quelled uprisings in Tibet and among other ethnic minorities, and it has pursued bilateral and multilateral relationships as well as trade with each of the actors in the See Johnston for a critique and analysis of the status-quo vs. revisionist literature. Alistair Johnston, “Is China a Status Quo Power?” International Security 27, 4 (Spring 2003): 5-56. 6 See Robert Jervis, Perception and Misperception in International Politics (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1976) for a discussion of spiral model and deterrent models of interstate relations. 7 Thomas Christensen, “Fostering Stability or Creating a Monster? The Rise of China and U.S. Policy Toward East Asia” International Security, Vol. 31, No. 1 (Summer 2006): 81. 8 Ibid. 5 3 region.9 However, the Taiwan issue and China’s military modernization have caused angst among regional powers and the United States. The second matter -- securing China’s status as a great power – has caused more concern for Chinese leaders. After a century of humiliation and its legacy of distrust of outside powers, the CCP is frequently unwilling to make concessions in the international arena for fear of being exploited. On the domestic side, the CCP faces a volatile public at home and must maintain a delicate balance between the powerful forces of nationalism and economic growth. Nationalism is a “potent force” that has been manipulated by the Chinese government to divert attention from domestic grievances in the past, but it has also backfired on the party in unexpected ways.10 Examples include the May 4th movement, the Hundred Flowers Campaign, and the Tiananmen Square massacre. Delivering stability to the Chinese people while gently nurturing the unifying tendencies of nationalistic sentiment will be an ongoing challenge to the PRC’s leaders. While controlling Chinese nationalism, the CCP must maintain stable and high economic growth. It has succeeded admirably at this task over the past few decades; however, given the globalized economy and China’s dependence on foreign consumption, the CCP may have difficulty sustaining China’s economic growth over the decades to come. The United States similarly faces a number of constraints internationally and domestically. On the international plane, the Obama administration must carefully protect U.S. influence through its security, economic, and diplomatic instruments while managing its withdrawal from Iraq, its drawdown in Afghanistan, and limited international political capital. Domestically, presidential and legislative elections are a year away, high unemployment concerns overshadow foreign policy interests, and gridlock between the administration and Congress makes policymaking of any kind a herculean task. Aside from these constraints, specific points of friction in Sino-American relations include the Taiwan issue and China’s military modernization. Since Chiang Kai Shek and the Nationalist Party (Kuomintang or KMT) fled to Taiwan during the Chinese Civil War, the U.S. and the CCP have been at odds over Taiwan’s status. While China views Taiwan as part of its sovereign territory (and therefore not subject to international meddling), the United States has established a series of precedents demonstrating American commitment to supporting the democratic aspirations of the people of Taiwan. The CCP, however, views Taiwan’s eventual reunification as critical to the party’s legitimacy and therefore is unwilling to harbor U.S. involvement in what it sees as a domestic affair. China’s rise has also been accompanied, not surprisingly, by increasing military might and corresponding friction with the U.S. In the wake of international condemnation of the Tiananmen Square massacre in 1989 and the incredible technological superiority demonstrated shortly afterwards by US forces during the First Gulf War, China set out to modernize its military and reduce its dependence on other powers. Deng Xiaoping’s strategy guiding the development of the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) envisioned the security of China’s borders 9 Taylor Fravel, “Regime insecurity and international cooperation,” International Security 30, no. 2 (2005), 46. Suisheng Zhao, “Nationalism’s Double Edge,” The Wilson Quarterly 29, no.4 (Autumn 2005): 77. 10 4 and the ability to use force to prevent Taiwan’s independence.11 Presidents Jiang and Hu have continued to fuel the PLA with annual double-digit budget increases. China’s annual defense budget for 2009 was $150 billion, an increase of 7.5% from the prior year. China colors its military modernization as a defensive measure designed to protect its security, but its policies have often put it at odds with the U.S. China disabled a U.S. intelligence plane in 2001, it harassed U.S. naval ships off its coast, and has bristled at recent U.S. – South Korean joint naval exercises.12 China is also developing sophisticated technology to be able to attack military forces at great distances when they attempt to deploy or maneuver in the vicinity of Taiwan (which China watchers call anti-access and area denial strategies).13 The test flight of the China’s J-20 stealth aircraft in January 2011 and the sea trials of its first aircraft carrier in August are merely the two most recent sources of friction between the two states. U.S. policymakers express deep concern over China’s growing defense budget, lack of transparency, and its assertive military posture. How should the U.S. assess Chinese aspirations in the near- and longterm, and how should it respond in the event of future military provocation? Opportunities While it is tempting to consider only the potential pitfalls that could stymie productive and mutually beneficial Sino-U.S. relations, a number of opportunities beyond the boundaries of traditional diplomacy exist. First, given the tremendous power that a combined effort by the U.S. and China represents, there is enormous potential for this bilateral relationship to achieve what no other bilateral relationship can. Because of their financial and trade interdependence, moreover, both states have incentives to see that neither one falters. This bilateral relationship represents over 1/3 of the world’s economic activity and almost a quarter of the world’s population. Some have described the locus of power in this century as the “G2.” Several open questions in the international community cannot be solved without the unified efforts of both the U.S. and China. Chief among these is the maintenance of a functioning and stable global economy. The U.S. and the China were key players in executing coordinated stimulus packages to head off the economy’s crash in 2008-2009. Secondly, climate change and environmental protection more broadly must be addressed by both states given that both have contributed to the problem and both stand to suffer from the depletion of the global commons. Third, the effectiveness of the United Nations Security Council as the body charged with providing for a stable international system has been in serious doubt as China and the U.S. routinely block collective action within the international community. A renewed agenda involving common priorities could breathe new life into an institution that many view as the source of international law. 11 David C. Gompert, François Godement, Evan S. Medeiros, and James C. Mulvenon, China on the Move: A Franco-American Analysis of Emerging Chinese Strategic Policies and Their Consequences for Transatlantic Relations, RAND, 2005, 39. 12 See David Sanger and Elisabeth Rosenthal, “U.S. Plane in China After It Collides with Chinese Jet,” New York Times, April 2, 2001; Thom Shanker and Mark Mazzetti, “China & U.S. Clash on Naval Fracas,” New York Times, March 10, 2009; and Elisabeth Bumiller and Edward Wong, “China Warily Eyes U.S. –Korea Drills,” New York Times, July 20, 2010. 13 Roger Cliff et al., Entering the Dragon’s Lair: Chinese Antiaccess Strategies and Their Implications for the United States, RAND, 2007, xiii-xiv. 5 Policy Prescriptions Given the uncertainty inherent in the international system, and in light of the domestic and international challenges faced by leaders on both sides of the Pacific, what policies should U.S. leaders support in their engagement with China? On the strategic level, what can China and the U.S. hope to achieve in the areas of proliferation of nuclear weapons, climate change, energy security, trade, institutions, alliances, and cyber security? Can the United States and China find common ground on a myriad of complex issues? How can the United States best leverage its influence in order to maintain its power in the region and the world? In the realm of economics, the U.S. regularly recites a litany of Chinese sins. China strategically depresses the value of its currency and thus gains an unfair comparative advantage over U.S. companies, accuses the US; China looks the other way while U.S. goods are pirated, leading US companies to lose billions of dollars each year; China attempts to steal U.S. company secrets, barraging American companies with cyber attacks. But to what degree can the U.S. use economic force to change these harmful economic practices? 14 The US might resort to tariffs and other protectionist measures, but it is not necessarily wise to use these tools against the chief holder of U.S. debt. U.S. policymakers worry that China may respond to U.S. economic force by dumping U.S. bonds and treasury notes to devastate the US economy, although in doing so China would depreciate one of its most valuable assets and compromise its chief export market.15 Due to U.S. military arms and equipment sales to Taiwan, military relations between the US and China have been spotty at best.16 What steps can the U.S. military take to thaw militaryto-military relations with China? Can the U.S. and China find an accommodation that avoids conflict? How should the U.S. respond to an increasingly assertive Chinese military? More broadly, how can U.S. policymakers, who tend to think in terms of presidential terms, effectively engage with Chinese policymakers who think in terms of dynastic cycles? Are there appropriate policies that balance between traditionally near-sighted U.S. policies and longterm Chinese foreign policy objectives? What alliances, nuclear posture, energy security, and regional engagement strategies will be able to most effectively advance U.S. interests without provoking an overreaction from China? Conclusion Managing the relationship with China is a critical task for U.S. policymakers. Americans sometimes view China’s rise as a relative power loss in a zero-sum game, and yet this relationship presents unprecedented potential for directing vast stores of political capital and economic resources towards the achievement of real and lasting global change. While the consequences of miscalculation and misperception loom large, the payoffs from a productive partnership are immense. America’s unipolar moment may be over. But as the United States recalibrates its position in the world, American policymakers can have an important impact by creating strategies that go beyond the boundaries of traditional diplomacy. 14 Economic force comes in the form of both carrots and sticks; it has the ability to compel, coerce, and attract other states. 15 Paul Krugman, “China, Japan, America,” New York Times, September 12, 2010. 16 Thom Shanker, “Pentagon Cites Concerns in China Military Growth,” New York Times, August 16, 2010. 6 Recommended Readings Christensen, Thomas. “Fostering Stability or Creating a Monster? The Rise of China and U.S. Policy Toward East Asia.” International Security 31, no. 1 (Summer 2006): 81-126. Christensen, Thomas. “Power and Resolve in U.S. China Policy.” International Security 26, No. 2 (Fall 2001): 155-165. Friedberg, Aaron. “The Future of U.S. – China Relations: Is Conflict Inevitable?” International Security 30, No. 2 (Fall 2005): 7-45. Ikenberry, John. “The Rise of China & the Future of the West.” Foreign Affairs 87, No. 1 (Jan/Feb 2008): 23-37. Mahbubani, Kishore. “Understanding China.” Foreign Affairs 84, No. 5 (Sep/Oct 2005): 49-60. Office of the Secretary of Defense. “Military and Security Developments Involving the People’s Republic of China, 2010.” Annual Report to Congress 2010. http://www.defense.gov/pubs/pdfs/2010_CMPR_Final.pdf Shambaugh, David. “Containment or Engagement of China?” International Security 21, No. 2 (Fall 1996): 180-209 Zhao, Suisheng. “Nationalism’s Double Edge.” The Wilson Quarterly 29, No.4 (Autumn 2005): 76-82. Zweig, David and Bi Jainhai. “China’s Global Hunt for Energy.” Foreign Affairs 84, No. 5 (Sep/Oct 2005): 25-38. Additional Readings Economic Policy Hughes, Neil. “A Trade War with China?” Foreign Affairs 84, No. 4 (July/Aug 2005): 94-106. Krugman, Paul. “China, Japan, America.” New York Times (12 September 2010). Miller, Ken. “Coping with China’s Financial Power.” Foreign Affairs 89, No. 4 (July/Aug 2010): 96-109. 7 U.S.-China Economic and Security Review Commission. 2009 Report to Congress. November 2009. http://www.uscc.gov Energy Policy Bradsher, Keith. “China Leading Global Race to Make Clean Energy.” New York Times (30 January 2010). Broad, William. “China Explores a Frontier 2 Miles Deep.” New York Times (11 September 2010). Political Policy Applebaum, Anne. “China’s Quiet Power Grab.” Washington Post (28 September 2010). Christensen, Thomas J. “The Contemporary Security Dilemma: Deterring a Taiwan Conflict.” The Washington Quarterly (Autumn 2002): 7-20. http://www.twq.com/02autumn/christensen.pdf. Christensen, Thomas J. “A Strong and Moderate Taiwan,” speech to US-Taiwan business Council, September 11, 2007. http://www.ait.org.tw/en/officialtext-ot0715.html Fishman, Ted C. China Inc.: How the Rise of the Next Superpower Challenges America and the World. New York: Scribner, 2005. Jacobs, Andrew. “China Warns U.S. to Stay Out of Islands Dispute.” New York Times (26 July 2010). Johnston, Alastair. “Is China a Status Quo Power?” International Security 27, No. 4 (Spring 2003): 5-56. Pehrson, Christopher J. “String of Pearls: Meeting the Challenge of China’s Rising Power across the Asian Littoral.” From the Carlisle Papers in Security Strategy. http://www.strategicstudiesinstitute.army.mil. Russ, Robert and Zhu Feng, eds. China’s Ascent: Power, Security, and the Future of International Politics. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2007. 8 Shambaugh, David. “Facing Reality in China Policy.” Foreign Affairs 80, No. 1 (Jan/Feb 2001): 50-64. Swaine, Michael D. “China’s Assertive Behavior - Part One: On ‘Core Interests,’” China Leadership Monitor, no. 34 (Feb 2011): 1-11. Wang, Jisi. “China’s Search for Stability with America.” Foreign Affairs 84, No. 5 (Sep/Oct 2005): 39-48. Military Policy Bumiller, Elisabeth and Edward Wong. “China Warily Eyes U.S. –Korea Drills.” New York Times (20 July 2010). Burles, Mark, and Abram Shulsky. “Patterns in China’s Use of Force: Evidence from History and Doctrinal Writings.” RAND, 2000. Fravel, M. Taylor. “China’s Search for Military Power.” The Washington Quarterly 31 (Summer 2008): 125-129, 135-139 Medeiros, Evan, et al. Pacific Currents: The Responses of U.S. Allies and Security Partners in East Asia to China’s Rise. RAND, 2008. Robinson, Peter and Gopal Ratnam. “Pentagon Losing Control of Bombs to China’s Monopoly.” Bloomberg Businessweek (29 September 2010). Ross, Robert. “China’s Naval Nationalism.” International Security 34, No. 2 (Fall 2009): 46-81. Wong, Edward. “Chinese Military Seeks to Extend Its Naval Power.” New York Times (23 April 2010). Strategic Thinking Friedberg, Aaron L. “The Struggle for Mastery in Asia.” Commentary (November 2000): 17-26. Goldstein, Avery. “An Emerging China’s Emerging Grand Strategy: A Neo-Bismarckian Turn?” In G. John Ikenberry and Michael Mastanduno, eds., International Relations Theory and the Asia-Pacific. New York: Columbia University Press, 2003, 57-106. Lai, David. “Learning From the Stones: A Go Approach to Mastering China’s Strategic Concept, Shi.” Strategic Studies Institute. May 2004. McCormick, Barrett. The Three Faces of Chinese Power: Might, Money, and Minds. Berkeley: Berkley Press, 2008.