Demand Curve - The Fast Food Sandwich

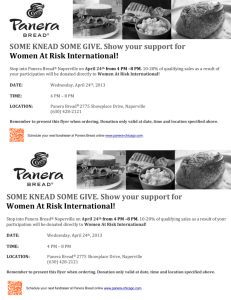

advertisement

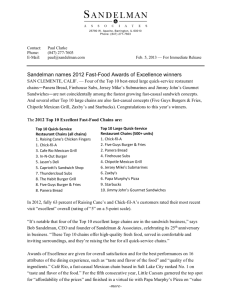

Reproducible Sheets Fast-Food Chains Upgrade Menus, and Profits, with Pricey Sandwiches by Shirley Leung For years, growth-obsessed fast-food chains expanded around the world without noticing the potential of a 75-cent item on their own menus. Only after that item—the humble cup of coffee—became the highpriced beverage behind Starbucks Corp. did fast-food executives search their kitchens for other undiscovered stars. Now they think they’ve found one: the sandwich. Lately, small restaurant chains with big ambitions have been racking up impressive sales by offering Americans upscale sandwiches as an alternative to burgers and fries. Some of those outlets, such as Cosi and Briazz, have names designed to convey European sophistication. Others, such as Corner Bakery Cafe and Panera Bread Co., have names that emphasize their use of fresh bread. All of them hope to win a big following among the nation’s aging and increasingly health-conscious baby boomers. . . . Above 99 Cents Though overall fast-food sales growth has been waning for years, growing numbers of American consumers have proved willing to pay as much for a sandwich as for the $4 cappuccino to go with it. That’s big news in an industry long accustomed to promoting 99-cent hamburgers or chicken nuggets. And it is making even some fast-food veterans rethink their marketing strategies. For example, roast-beef specialist Arby’s Inc., a unit of Triarc Cos., has launched a new line of Market Fresh sandwiches, which are served on thick slices of bread, instead of a bun, and cost about $4 apiece, about 50 per cent more than its average fare. . . . In the US, sales of custom-made sandwiches are rising 15 per cent a year, much faster than the 3 per cent growth rate for hamburgers and steaks, says Technomic Inc., a Chicago food-consulting firm. That helps explain why Panera Bread Co., the largest player in the premium-priced sandwich category, saw its share price nearly triple last year. Panera, which is based outside St. Louis, rang up sales of $529.4 million for 2001, up 50 per cent from the previous year, and it is expected to report an about 80 per cent increase in net income for 2001. The company had average sales per store of $1.75 million in 2001, compared with McDonald’s $1.6 million. In 4 p.m. trading on the Nasdaq Stock Market Monday, RS 4-7 Panera’s shares rose $3.28, or 5.3 per cent, to $64.65 on volume of 758 500 shares, more than double its average daily volume for the past three months. Panera and some other high-end sandwich chains also sell gourmet coffee, meaning that success on a national scale could steal sales from their role model, Starbucks. But the chains vying to carve out an empire based on sandwiches face a challenge that Starbucks never did—a field of well-funded competitors. Starbucks, which expanded to roughly 4100 stores in North America in little more than a decade, was helped by a dearth of big-chain competition. Even today, its largest competitor, Diedrich Coffee Inc., based in Irvine, California, has a total of only 380 outlets. “Very Difficult” “The probability of any of these sandwich chains becoming a Starbucks is a major question,” says Dennis Lombardi, Technomic’s executive vice president. “It is going to be very difficult.” Yet the prospect of spinning prosperity out of a commodity long taken for granted, of dotting the landscape with a recognizable logo, of becoming synonymous with a particular product, is proving seductive. . . . Until recently, the sandwich was hardly considered cuisine. According to popular lore, it was invented solely to allow the Earl of Sandwich to eat without leaving the gaming table. Its culinary status sank even farther when the fast-food industry began to tout it as a low-cost meal, available at most big purveyors for as little as 99 cents. By contrast, the new sandwich shops treat sandwich-making as an art. Fresh-baked bread is the basis of their strategy for improving the sandwich’s image. Sure, the tomato slices are fresh, and the meat is carved off homestyle roasts. But the big difference is what some of the chains call “artisan bread.” Panera employs professional bakers at $13 an hour to make bread from scratch throughout the day. Together, Panera and Smyrna, Georgia-based Atlanta Bread Co. offer more than two dozen kinds of bread, including asiago cheese, nine grain, kalamata olive, and sundried tomato. At New York-based Cosi Inc.’s restaurants, bread that’s been out of the oven for 30 minutes or more is tossed away unused. © Oxford University Press (Canada) 2003. Permission to reproduce for classroom use restricted to schools purchasing Economics Now. Reproducible Sheets Fast-Food Chains Upgrade Menus, and Profits, with Pricey Sandwiches (continued) The finished products feature names as fancy as the coffee specialties at Starbucks. The menu blurb describes Panera’s Frontega Chicken Panini as: “Smoked and pulled white-meat chicken, red onion, mozzarella, tomato, chopped basil, and our chipotle mayo, on our rosemary focaccia.” Compare that with the Big Mac: “Two 100-per-cent-beef patties, sesameseed bun, American-cheese slice, Big Mac sauce, lettuce, pickles, onions, salt, and pepper.” Of course, the price of the Frontega is $5.75, about $3 more than for the typical Big Mac. The average check is $6.25 at Panera and $8 at Cosi, more than twice that at most burger joints. But the chains can make these prices stick because of a major shift in the demographics of fast-food customers. The industry’s traditional diner is male, between five and 24 years old, and typically short on cash. But now that youthful segment of the population is expected to grow by only 5 per cent over the next decade, while the 45- to 64-year-old population will grow about 30 per cent, according to the US Census Bureau. And compared with previous generations in their current age group, baby boomers are less likely to eat at home. Pressed for time, they want food fast. Moreover, the growing availability of healthier and higher-quality sandwiches has eroded their loyalty to fast-food burgers. RS 4-7 “If the value is there, I’ll certainly pay the price,” says Karen Davis, a 45-year-old Chicago real estate developer and self-described former burger fan who says she, her husband, and nine-year-old daughter visit Panera about five times a week. Subway Restaurants still dominates the sandwich arena, with more than 13 200 US outlets. Until lately, the privately held chain competed with other fast-food purveyors on price, charging about $3 a sandwich. But 18 months ago it, too, started going after more affluent consumers. The chain now offers as many as five different breads, including Asiago Caesar and Sourdough. “We made the food more interesting,” says founder Fred DeLuca. Likewise, some of the nation’s other fast-food chains are seeking to rev up their sales growth by adding gourmet sandwiches or premium breads to their menus. But some of them are finding that many of the new sandwich diners also want atmosphere, something that Subway and many other more traditional fast-food chains may be ill-equipped to provide. . . . Source: Shirley Leung, “Fast-Food Chains Upgrade Menus, and Profits, with Pricey Sandwiches,” from Wall Street Journal Online, 5 February 2002. Reprinted by permission. Questions 1. Is the growing popularity of the sandwich best represented as a movement along the demand curve, or a shift of the whole demand curve? Briefly explain. 2. Your text explains five basic changes that can change customer demand for a product. Consider each one, and in a sentence or two, decide if it applies to the sandwich story. 3. What long-range effect might the popularity of the sandwich have upon “traditional” fast food? Have you noticed any changes in the fast-food outlets you patronize? © Oxford University Press (Canada) 2003. Permission to reproduce for classroom use restricted to schools purchasing Economics Now.