Session 5 Economic cycles

advertisement

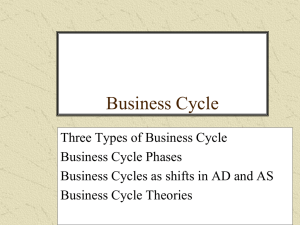

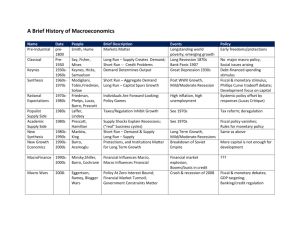

Module H4 Session 5 Economic Concepts for Statisticians Session 5 Economic cycles At the end of this session, students will have an understanding of: Consumer and investor behaviour Business cycles Technology (and other long-wave) cycles Poverty traps and low-level equilibria in developing countries Consumption and investment Why are we interested in consumption and investment? Remember the equation: Y=C+I+G+X–M (from Session 2) This equation tells us that the first two components of national output are private consumption expenditure (C) and private investment expenditure (I). Consumption and consumer behaviour Consumption (by which we normally mean private consumption) is the largest component of expenditure in an economy. So it is important to understand what drives it and how it is likely to change in response to different factors. Income Economics tells us that the most important factor driving consumption is income. The ‘average propensity to consume’ (APC) is the proportion of total income which is spent on consumption, i.e. C / Y. The ‘average propensity to save’ (APS) or ‘savings ratio’ is the proportion of total income which is spent on savings, i.e. S / Y. And Y = C + S. Often, we use disposable income as the denominator (i.e. income minus taxes, T), thus: APC = C Y T and SADC Course in Statistics APS = S Y T Module H4 Session 5 – Page 1 Module H4 Session 5 Discussion 1 Total income of employees in the manufacturing sector is US$20 million. Disposable income (i.e. what the employees receive net of tax) is US$16 million. If APC among manufacturing employees is 0.95, what is S in this sector? And what is C? _______________________ We are also interested in what happens to consumption and savings when disposable incomes change. In the 1930s, John Maynard Keynes (see Session 1) put forward the idea that as income increases, people’s consumption also increases but by less than the increase in their income. Keynes developed the idea of ‘marginal propensity to consume’ (MPC): MPC = change in consumption change in income MPC is normally <1 (as Keynes argued), but it could be > 1 if people borrow to fund consumption. Discussion 2 If a US$100 increase in income leads to a US$80 increase in consumption, then MPC = 0.8. What is MPS? Other factors Apart from income, other factors also affect consumption and savings behaviour: Wealth. If people feel better off because of an increase in the value of their assets (e.g. a house, land, or company shares), they are likely to consume more. This is known as the ‘wealth effect’. They may borrow against their assets to consume more. Credit and interest rates. In countries where consumer credit is easy to obtain, people often borrow to buy consumer durables such as a fridge, television or washing machine. An increase in credit availability and/or lower interest rates will lead to increased consumption of such items, while scarce credit and/or higher interest rates will reduce consumption. Inflation. Price increases mean that people’s purchasing power with a given amount of money declines, so they tend to save more (consume fewer ‘luxury’ SADC Course in Statistics Module H4 Session 5 – Page 2 Module H4 Session 5 items) in order to be able to continue to meet basic needs. However, at very high levels of inflation, households have to use all their income as soon as they get it to buy basic needs goods – in which case they consume everything and cannot save. Expectations and uncertainty. People may alter their consumption (and savings) behaviour on the basis of what is likely to happen in future e.g. an expected inheritance of wealth, or an expected salary increase. They may save if they fear losing their job, or in case they get ill (‘precautionary savings’). Life cycle hypothesis. This view says that when people consume, they take into account not only their current income but probable variations over their lifetime. e.g. a 25-year old junior professional who expects to be promoted to management may take out a loan to buy a car – in other words, consume more than his income – because he expects to have a higher income later. His greatest earning capacity will be in middle age, when he will pay off his debts and save money for retirement. The permanent income hypothesis (Milton Friedman, see Session 1) argues that people have a rough idea of how much they will earn over their lifetime and they dislike large changes in consumption, so they average out consumption in relation to their average lifetime income (‘permanent income’). Thus, consumption only changes if people re-evaluate their permanent income position – by contrast with the Keynesian view, where consumption changes if current income changes. Demographics. Households with large numbers of elderly people and children tend to consume most of their incomes, they may even consume more than their incomes – by running down savings or borrowing. Households made up mainly of young or middle-aged economically active adults are more likely to be able to save. Discussion 3 The economists who put forward these ideas about the factors affecting consumption were working within the context of industrialized economies. In developing countries: How relevant/irrelevant are these factors? Do you think consumer behaviour is more likely to be affected by current income (Keynes) or permanent income (Friedman)? Can you think of any parts of your economy in which there may not be much of a link between income and consumption? SADC Course in Statistics Module H4 Session 5 – Page 3 Module H4 Session 5 Investment and investment behaviour Private consumption expenditure (C) is generally the largest component of GDP. Table 1 suggests that we might expect C to account for between half and three quarters of GDP – with some outliers, such as Botswana. By contrast, private investment expenditure (I) generally accounts for a smaller proportion of GDP. However, it is disproportionately important because investment is a key driver of economic growth (see Sessions 3 and 4). Table 1: Consumption and investment in selected SADC countries, the UK and US Private consumption expenditure (% of GDP) Gross fixed capital formation (% of GDP) Botswana 2001-02 29 24 Malawi 2004 79 1 Mozambique 2002 74 21 Namibia 2006 (preliminary) 51 28 Swaziland 2002-03 74 12 UK US 1st quarter 2007 65 18 1st quarter 2007 70 16 Note: Gross Fixed Capital Formation = acquisitions minus disposals of fixed assets, plus improvements to natural assets such as land. It includes private investment (I) and government investment (part of G). Source: Data/calculations using data from national statistical office websites, accessed August 2007. What is investment? Economists define investment as addition to capital stock – the physical capital used to produce goods and services. Ordinary people often use the terms ‘investment’ and ‘savings’ to mean the same things – for instance, investing by depositing money in the bank or buying shares, but economists call this saving. Only when a person buys machinery, equipment, buildings, land etc. for the purpose of producing goods and services, is that person investing. We call him/her an investor or ‘entrepreneur’. What drives investment? The most important factor affecting individual investor decisions is the interest rate. Entrepreneurs compare the expected rate of return of an investment with the interest rate, because they need to borrow money to finance the investment. If the expected rate of return is higher than the cost of borrowing, they will make the investment. Therefore low interest rates encourage investment. Even if someone is investing their own money (or retained profits), rather than borrowing, the interest rate is important because they could have kept their money in the bank and earned interest on it. If the money they would have earned in the bank is more than they SADC Course in Statistics Module H4 Session 5 – Page 4 Module H4 Session 5 would earn on their investment, then there would be no point in investing! – the ‘opportunity cost’ of the investment would be too high (see Session 1). In fact, investors need the rate of return on their investment to be higher than the interest rate, to compensate for the risks involved in investing. A major challenge for the authorities in developing countries is to keep interest rates low enough to encourage private investment1. There are also other factors which affect investor decisions: Expectations or ‘animal spirits’ (in the words of Keynes) – i.e. the extent to which entrepreneurs are confident/enthusiastic about the outcome of their investments. The cost of inputs, in particular machinery and equipment. Access to new technology, which increases the productivity of investment. The investment climate, including crime/security levels, tax burden, etc. The rate of change of income, profits or cash flow (if, as some economists argue, entrepreneurs’ decisions are sometimes influenced more by past performance and earnings than by a rational calculation of potential returns in the future). Business cycles We think of output as growing at a trend rate – for instance, in Session 3 we quoted Miles and Scott (2005), who referred to the US economy as having grown at an annual per capita rate of 1.75% since 1870. But of course the growth rate of an economy is not constant. Output fluctuates – often sharply – in the short term. We call fluctuations of less than a decade in length ‘business cycles’. 1 This is a simplified account of the issues, which are in fact more complex owing to the rapid development of new financing mechanisms for businesses (other than bank loans) over the past three decades. These range from the issue of shares on a local stock market to sophisticated international financial instruments. Nevertheless, bank interest rates remain a good indicator of opportunity cost, particularly in developing economies. SADC Course in Statistics Module H4 Session 5 – Page 5 Module H4 Session 5 Y Boom Boom Recovery Trend output Actual output (GDP) Recession Slump Time The graph shows a stylised drawing of a business cycle. The black line can be drawn using GDP figures. The blue line must be added in by analysts who estimate what trend output should be. Only when we have done this, can we describe the business cycle. As Miles and Scott (2005) point out: “We do not actually observe the business cycle – we only observe GDP. To measure, the business cycle, we have to make assumptions about trend output”. The terminology associated with the study of business cycles is confusing. For instance, in the above graph, we see a boom, recession, slump (or trough) and recovery (or expansion). But alternatively, a period of negative growth may be called a contraction (if very short), a recession (if output falls for at least two quarters), or a depression (if prolonged and severe, as in the Great Depression of 1929-32). One term which all economists agree on is the ‘output gap’, which refers to the difference between actual and trend output (shown by the red arrows on the graph). The output gap is positive if GDP is above trend output, and negative if GDP is below trend output. Exercise 1 Using GDP growth data from the UK Office for National Statistics website, draw a graph of growth for the UK economy from 1970 to date. When did recessions occur? Can you think of what might have caused them? SADC Course in Statistics Module H4 Session 5 – Page 6 Module H4 Session 5 Causes of business cycles The causes of variations in output over the business cycle fall into three categories, all of them known as ‘shocks’. Shocks are changes in the conditions facing the economy – whether originating inside the economy (internal shock) or outside it (external shock): 1. Real demand shocks, where there is an increase or decrease in one of the components of aggregate demand (C, I, G or X-M). 2. Nominal demand shocks, where there is a change in the money supply, e.g. the central bank prints money leading to increased demand for goods and services, which leads output to rise (before producing inflation). In this case, there is no real change, but people have more cash to spend so demand increases. 3. Supply shocks, such as an oil price increase or a technological innovation. Most analyses indicate that demand shocks are more important than supply shocks. Are recessions good or bad? There are two main schools of thought among economists about the desirability of recessions: The traditional view, and its recent expression in the form of the Real Business Cycle model, is that a recession is a natural way for an economy to adjust to an internal or external shock. It adjusts via the price mechanism (prices, wages and interest rates) until output returns to its trend level. During the process, weak and uncompetitive firms are eliminated, resulting in a healthier economy. The view put forward by Keynes, on the other hand, is that widespread market failures prevent the price mechanism from working properly and returning the economy to its long-run trend position. Market failures include monopolies, ‘sticky’ wages (when wages do not fall even though unemployment is high), poor information and underdeveloped financial systems. For Keynes, recessions were not beneficial. Governments could intervene to help the economy return to its trend output using fiscal policy (increased government spending, see Session 8) and monetary policy (e.g. lower interest rates, see Session 6) to boost aggregate demand. SADC Course in Statistics Module H4 Session 5 – Page 7 Module H4 Session 5 C and I in the business cycle Consumption moves in the same direction as output during the business cycle, but it fluctuates less than output over the cycle. One reason that C is less variable than output (GDP) may be because people try to smooth their consumption over the cycle, avoiding big cut-backs in a recession if at all possible because they have a long-term view of income (as the permanent income hypothesis suggests). Another reason may be that although employee wages may be hit by recession, they do not normally suffer as much as output – or grow as fast as output during the expansion and boom phases. However, Miles and Scott (2005) argue that while it is true that C varies less than output, recessions do hit some consumers hard – particularly the poorest and most vulnerable. Investment on the other hand is strongly pro-cyclical, i.e. it moves in the same direction as output during the business cycle and shows bigger variations than output during the cycle. Sectors and the business cycle Different sectors of the economy are affected differently by business cycles. The sector which shows the biggest variations is construction: this is where the signs of a slowdown will appear first, and it is this sector which will normally grow fastest during a boom. Technology (and other long-wave) cycles In addition to the short- to medium-term cycles known as ‘business cycles’, economists have identified other possible cycles which take place over a longer period of time. The main ones are: 1. The Kondratiev or technology cycle. A Russian economist, Nikolai Dmitrievich Kondratiev (1892-1938), and an Austrian economist, Joseph Schumpeter (18831950) suggested that big new discoveries, when converted into technological innovation (see Session 4) give rise to periods of prosperity which last for several decades. The cycle continues until all the potential of that particular technology to generate new products is exhausted – at which point there will be a slowdown until another wave of innovation occurs. Some of the big changes in the past have been associated with railways (19th century) and motor vehicles, electricity and plastics (20th century). The current cycle is based on computers and biotechnology. SADC Course in Statistics Module H4 Session 5 – Page 8 Module H4 Session 5 2. The Kuznets cycle. Another type of cycle was identified by the US economist Simon Kuznets (1901-1985), who found evidence for cycles linked to real estate construction (building) which last 15-20 years. Poverty traps and low-level equilibria In Session 4, we discussed endogenous growth theory which says that there is no automatic catching up by poorer countries because of the role of human capital and technological innovation in growth. Developing countries have to make a big effort to catch up. This effort involves investment in physical and human capital, technological effort and a sound social, political and institutional framework. The implication is that if developing countries do not achieve this, they will remain poor. Often, the reason for failure is poverty in the first place: because of poverty, there is a lack of capacity to invest, to take part in technological innovation or to sort out social, political and institutional problems, so poverty continues. This vicious circle is called a poverty trap. In this session, we have looked at business cycles, which describe fluctuations around the trend output path for the economy. Here, we find a similar problem – but for different reasons. Keynes argued that even if a country has been on a strong growth path, a recession may become a trap from which it is hard to escape – in other words, what might have appeared to be a temporary fall in output (recession) becomes permanent. This is often referred to as a low-level equilibrium or low output equilibrium. What does this mean? When economists first started discussing the idea of equilibria, they assumed that there was only one possible equilibrium position for the economy, which was where markets cleared and the economy was at full output and employment (see Session 1). However, Keynes argued that once the economy was in recession, the existence of market failures might prevent it from returning to this full output equilibrium. At this point, there might also be a problem known as coordination failure: each entrepreneur would be waiting to see if another would invest before risking his/her money – with the result that nobody would invest and the economy would remain at a low level of output! This line of thought suggested the idea that there might be more than one equilibrium position for an economy (‘multiple equilibria’). A country might get stuck at a ‘low-level equilibrium’ or ‘low output equilibrium’ – a position below its full output and employment potential. Market forces would not automatically extract it from this position. SADC Course in Statistics Module H4 Session 5 – Page 9 Module H4 Session 5 Discussion 4 The ideas of poverty traps and low-level equilibria both provide justifications for government intervention in the economy, but the justifications are different and so are the interventions required… What is the ‘poverty trap’ justification for government intervention, and what type(s) of intervention is/are required? What is the ‘low-level equilibrium’ justification for government intervention, and what type(s) of intervention is/are required? Do you think that either – or both – types of intervention would be a good idea in your country – or would non-intervention be a better strategy? References Anderton, A.G. (2000) Economics, 3rd edn. Causeway Press, Ormskirk, Lancashire, UK. Miles, D. and Scott, A. (2005) Macroeconomics – Understanding the Wealth of Nations, 2nd edn. John Wiley & Sons, Chichester, West Sussex. SADC Course in Statistics Module H4 Session 5 – Page 10