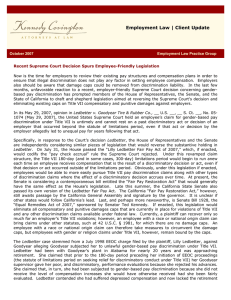

View as DOC - Post & Schell, PC

advertisement

Ledbetter Decision Likely to Result In Earlier Charge Filings The Legal Intelligencer By Sid Steinberg June 13, 2007 Ledbetter v. Good Year Tire & Rubber Co. Inc., the U.S. Supreme Court extended to "paysetting decisions" its previous line of cases holding that the time for filing a charge of employment discrimination begins when the discriminatory act occurs. Specifically, the court declined to extend the charge-filing period to include paychecks, issued within the period, which may be presently effected by discriminatory decisions made outside the filing period. This decision has sparked a debated among commentators as to whether it will increase the number of charges filed or simply result in earlier charges when discrimination is suspected. Lilly Ledbetter worked for Goodyear from 1979 to 1998. During most of this period, she and other salaried employees were given or denied raises based upon their supervisors' performance evaluations. Ledbetter was consistently among the lowest-rated managers, and her pay lagged consistently behind that of her male peers. She did not file a charge of discrimination following any of her performance reviews. In March 1998, however, Ledbetter submitted a questionnaire to the EEOC alleging that she had been discriminatorily transferred. Her formal charge of discrimination, filed in July 1998, added an allegation that she had received a discriminatorily low salary as a manager because of her sex. Ledbetter subsequently accepted early retirement in November 1998. At trial, the jury found in favor of Goodyear on Ledbetter's transfer-related claims, but it returned a verdict in her favor on her Title VII pay claim. The jury heard evidence that "during the course of her employment several supervisors had given her poor evaluations because of her sex, that as a result of these evaluations her pay was not increased as much as it would have been if she had been evaluated fairly, and that these past pay decisions continued to effect the amount of her pay throughout her employment." There was, as noted, no dispute that at the time of Ledbetter's retirement, she was paid significantly less than similarly situated male managers. Goodyear appealed the district court's denial of its motion for JMOL on the grounds that her claim of pay disparity was limited to the charge-filing period. The 11th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals reversed the district court's decision, finding that the charge-filing period was triggered by the last "affirmative decision" affecting her compensation. The appellate court found that there was no such "affirmative decision" regarding Ledbetter's pay within 180 days of her charge (as Alabama is a non-deferral state). As such, Ledbetter's claim for wage discrimination under Title VII was time-barred. The Supreme Court granted certiorari. Justice Samuel Alito wrote the 5-4 majority decision affirming the 11th Circuit's reversal. The court found that Ledbetter's claim fell squarely within its precedent that the EEOC charging period is triggered when a discrete unlawful practice takes place. Moreover, in line with, among other decisions, Delaware State College v. Ricks and National Railroad Passenger Corp. v Morgan, "a new violation does not occur, and a new charging period does not commence, upon the occurrence of subsequent non-discriminatory acts that entail adverse effects resulting from the past discrimination." Specifically, the court rejected Ledbetter's argument that each diminished paycheck renewed the charging period for prior discriminatory acts affecting the present paycheck. The court rejected this argument on the grounds that "current effects alone cannot breathe life into prior, uncharged discrimination; as . . . such effects in themselves have no present legal consequences." The court analogized Ledbetter's situation to the one it had previously addressed in Ricks. In that case, the court found that a college librarian's claim of discrimination accrued when he learned that his bid for tenure had been denied, one year prior to his actual dismissal from the school. In Ricks, the court held that the EEOC charging period ran from "the time the tenure decision was made and communicated," and was not extended by the ultimate effect of the decision (i.e. his departure from the college). Applying Ricks to Ledbetter's claim - the court found that the discriminatorily poor evaluations earlier in Ledbetter's career (and the diminished raises that accompanied the evaluations) triggered the chargefiling period. The subsequent paychecks were simply the ultimate effect of these prior decisions. The dissent argued, "compensation disparities [in contrast to other employment decisions] are often hidden from sight. [H]aving received a pay increase, the female employee is unlikely to discern at once that she has experienced an adverse employment decision. She may have little reason even to suspect discrimination under a pattern develops incrementally and she ultimately becomes aware of the disparity." In this respect, the court analogized the cumulative effects of pay disparity to hostile work environment claims which may accrue "over a series of days, or perhaps years . . . ." Commentators have already lined up to dispute the practical effect of the Ledbetter decision. A number of plaintiffs attorneys have argued that the decision will cause employees to file more, and earlier, charges, on the grounds that it is safer to challenge an employment action that might effect pay, rather than risk having a wage discrimination claim under Title VII found to be time-barred years later. On the other hand, this possible "flood" of EEOC charges seems unlikely. It is, at present, the rare employee who believes that he or she has been discriminatorily evaluated and yet keeps this belief to him or herself. In Ledbetter, the evidence was that she had received "poor evaluations because of her sex" in the (relatively) distant past. It is uncommon, to say the least, for an employee to receive what he or she believes to be an unfairly negative evaluation without challenging the same. The court found this to be part of Congress' intent in creating short deadlines for the filing of EEOC charges. That is, "this short deadline reflects Congress' preference for the prompt resolution of employment discrimination allegations through voluntarily conciliation and cooperation." SID STEINBERG is a partner in Post & Schell’s business law and litigation department. He concentrates his national litigation and consulting practice in the field of employment and employee relations law. Steinberg has lectured extensively on all aspects of employment law, including Title VII, the FMLA and the ADA.