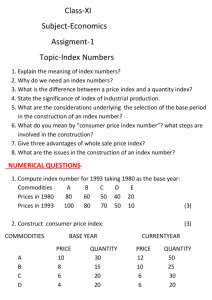

The Curse of Volatile Food Prices

advertisement