improving-schools-in-nottimgham - Faculty of Humanities

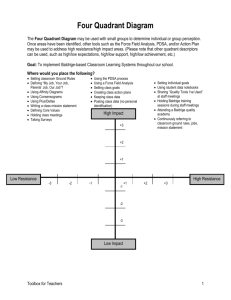

advertisement