Transcript of this slide

advertisement

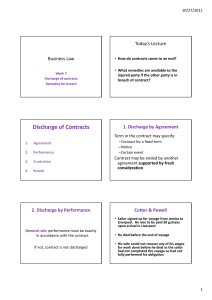

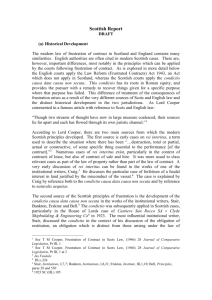

CONTRACT LECTURE 12 TRANSCRIPT C STRICKLAND FRUSTRATION TOTAL TIME = 55 mins 34 secs Track/slide 4 3.29 Now we can note a little on the origins and justification for the doctrine of frustration. The doctrine of frustration grew up in the courts to avoid the harsh rule at common law that if you make a contract you have to perform it; if you cannot perform it you are in breach of contract and feel the consequences of being in breach of contract EVEN if the breach was beyond your control. In this way liability for breach of contract is seen as STRICT – it makes no difference whether or not you were at ‘fault’. The case that demonstrates this harsh common law approach is Paradine v Jane 1647. In this case a tenant farmer was dispossessed of his farm by the King’s enemies. Despite this, and although not at fault, when he claimed that he should not be liable to pay the rent for the period of 2 years he was dispossessed, it was held that he had to pay the rent because of the ‘absolute’ nature of his contractual obligations. Thus, the common law courts were making the point that the courts would not interfere with the contracts made between 2 parties – holding true to the idea of laissez faire. However, this very ‘absolute’ approach has gradually been diluted, though not very much. The doctrine of frustration is such that the courts will allow a party to escape the rigours of being held to be in breach of contract if somehow he can show that the contract was frustrated. However, the courts do not allow frustration of contract to be successfully pleaded very often – harping back to the notion in Paradine v Jane. The key early case allowing the absolute nature of contractual obligations to be weakened by the idea of frustration is Taylor v Caldwell 1863. The cases that have followed do allow frustration for some reasons but the courts are still very reluctant to find it. Although the doctrine of frustration is now firmly established in contract law, the justification for it is unclear. In the case of National Carriers Ltd v Panalpina (Northern) Ltd 1981 we can see 5 possible bases for the doctrine as expounded by Lord Wilberforce and Lord Hailsham. Lord Wilberforce stated that in his opinion the 5 justifications really ‘shade into one another and that a choice between them is a choice of what is most appropriate to the particular contract under consideration the doctrine is and ought to be flexible and capable of new applications.’