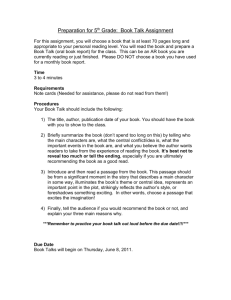

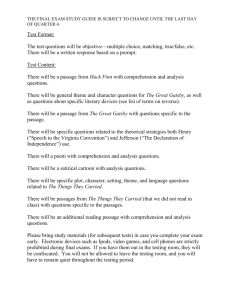

SAT

advertisement