1ac [2/15] - DunbarHSDebate

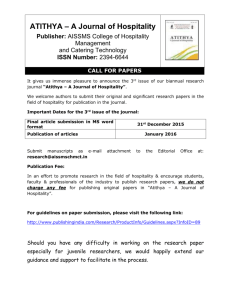

advertisement

![1ac [2/15] - DunbarHSDebate](http://s3.studylib.net/store/data/008993453_1-5d7c7c66c65929d92d5f757a9392b4d0-768x994.png)