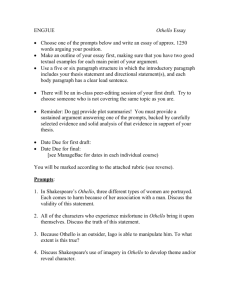

Roux on Postcolonialism - Dr. DR Ransdell, University of Arizona

advertisement

Roux, Daniel . “Hybridity, Othello and the Postcolonial Critics.” Shakespeare in Southern Africa . Grahamstown: 2009. Vol. 21 pg. 23, 8 pgs Full Text (4618 words) Copyright Institute for the Study of English in Africa 2009 At least since Frantz Fanon' s Black Skin, White Masks was published in 1952, the postcolonial subject has been defined in relation to split subjectivity, hybridity and alienation. Academics and writers almost routinely invoke two ur-texts in order to discuss something of the problematics surrounding colonisation and the negotiation of race and Otherness: Shakespeare's The Tempest and Othello. In the case of Othello, there is often a visceral reaction to the black character on stage, a dislocating shock of recognition: thus for Ben Okri, it becomes possible to imagine himself in Othello's place, Othered as much by the Venetian social context that the narrative describes as by the play's own potentially racist symbolic. For Caryl Phillips, a personal comparison with Othello, both intimately inserted into and simultaneously alienated from the turbulent cosmopolitan centre of Early Modern Venice, is almost inescapable. In Othello, a generation of critics have recognised a trajectory described by Ania Loomba in Gender, Race, Renaissance Drama: Othello moves from being a colonized subject existing on the terms of white Venetian society and trying to internalize its ideology, towards being marginalized, outcast and alienated from it in every way, until he occupies its 'true' position as its other. (48) Something that strikes one about this way of understanding Othello as a character is that it affords him a kind of ontological priority: he is read as if he is a black subject who has somehow stumbled into Shakespeare's play. His predicament is read as analogous or somehow illustrative of the predicament of the postcolonial subject. It is as if there is an organic flesh-and-blood person beneath the textual imposition, a subject who invites a transformative face-to-face encounter, an electric shock of recognition and kinship that enables the defamiliarisation of the colonial world that Shakespeare's play anticipates but precedes. Othello's attempts to translate himself into a Venetian, his self-division and his complex hybridity appear to hold a mirror to all the signal characteristics of the postcolonial subject, at least in academic discourse. By now a venerable host of critics have warned sternly against projecting our own language of race onto the Early Modern context, pointing to the fraught and ambiguous situation of African nobility and diplomats in Elizabethan England, the collusion of a language of race with a language of religion during this period, and the historically specific byzantine distinctions that governed popular understanding of the Other. These Historicist correctives nonetheless still seem to imply - in fact, they strengthen the sense - that the character Othello's history and culture somehow reside intact in a kind of textual palimpsest: that a correct, attentive reading might somehow surface an Othello that lives beyond the text even as he inhabits it, an Othello momentarily apprehended in history by Shakespeare's play. Of course, there is nothing new in responding to Othello as if its characters are real - perhaps testimony to the brilliance with which Shakespeare explores and utilises the rhetoric of pity. Of all Shakespeare's plays, Othello is most notorious for soliciting outbursts from the authence: sighs, exclamations, fainting spells. Stendhal even reports that a soldier in Baltimore shot at the actor playing Othello in an 1822 production of the play and broke his arm after exclaiming, "It will never be said in my presence a confounded Negro has killed a white woman" (Stendhal 3839). While postcolonial critics undoubtedly adopt a more nuanced and sophisticated attitude towards the play's textual strategies than the soldier in question, it is difficult to escape from the sense that there is an echo of this mimetic fallacy at work in the kind of criticism that invokes Othello to talk about postcolonial subjectivity. Shakespeare was undoubtedly attentive to the oppressive role of ideology, to the predicament of the outsider, to the importance of narratives in mediating our experience of self and world. Perhaps he knew something about the actual people called 'Moors' in Venice in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. But we have been schooled, most notably by postcolonial theory itself, to de-emphasise these kinds of questions, since they rest on untestable assumptions about authorial intention and experience. One could answer that in Othello we encounter a dissection, or perhaps even an imposition, of a particular ideological mechanism; but in the moment of identification with Othello as a victim of the mechanism, or as in some way illustrative of the personal consequences of this mechanism, he becomes a real person, or opens the textual space for a body - perhaps the body of the critic herself. What I want to argue here is not that Othello should not be used by postcolonial critics. It is really that the trend to read Othello's pain, self-division and volatility as the real consequences on a real person of an inchoate colonial discourse calls into question certain assumptions of postcolonial theory. In this sense, what I see as a misreading of Othello is really symptomatic in fact, it enables - one particular understanding of the postcolonial subject that I think we need to interrogate very carefully. In this sense, Othello remains an absolutely crucial text in postcolonial studies. I would argue that the play engages narrowly with Early Modern humanism, with Renaissance constructions of an occidental, individuated self, and that Othello's alienation and self-division, potently signaled by his blackness, is an inexorable aspect of this process. Categories that seem so effortlessly to describe the predicament of the postcolonial subject are in fact born out of Western self-definition: not, as the academic cliché goes, by serving as its Other, but in fact as an absolutely integral aspect of self-definition, one of the superimposed templates through which Western individuality has come to recognise and contemplate itself. The self as split, hybridised, deracinated and alienated exists in a dialectical relationship with the celebrated autonomous subject of humanism: they are one and the same thing. That is not to say that these categories might not touch in very real and illuminating ways on the experience of deterritorialisation, reterritorialisation and division that our postcolonial moment has produced. But the central preoccupations of much postcolonial thought, including its semi-tragic celebration of plasticity, self-translation, the fusion of boundaries and the translations that attend on travel and dislocation, have a long history of involvement in specifically Western art and philosophy. They might not be inaccurate in terms of describing postcolonial experience, but they belong to an epistemology that is really preoccupied with the vicissitudes of the autonomous humanist self in the West: a point that Robert Young makes about hybridity in a somewhat different context in his book Colonial Desire. To be more specific, consider Christopher Marlowe's rather strange play Dido, Queen of Carthage, written about 20 years before Shakespeare wrote Othello. Here we have Aeneas, the founder of Rome, stranded in Africa, in a rather neat inversion of the cultural and racial dynamic of Othello. From the outset, he seems inadequate to the mythical role that history has scripted for him: he faints at Queen Dido's feet when she asks him to dinner and responds to even the simplest questions, such as "What stranger art thou, that dost eye me thus?" (2.1.74), like a panic-stricken deconstructionist: "Sometime I was a Trojan, mighty Queen;/But Troy is not; what shall I say I am?" (2.1.75-76) Throughout the play, he fails properly to identify himself, to render any plausible account of his own actions, and is still described in the last scene of the play by Dido as a "stranger" (5.1.285) - despite their love affair. When he encounters a depiction of the battle of Troy, he seems to forget that he is in Carthage, has a weeping fit, and to his friends' embarrassed discomfort wishes that he could be supplanted by the images that he sees: to die so that they can live. In contrast, in Virgil's nationalistic Roman epic (which is of course Marlowe's main source for the play), Aeneas feeds his spirit on the images of Troy that he finds in Carthage: in fact, Virgil draws attention to the contrast between the inanimate nature of the depiction and the vitality that the spirit finds in them (1.463-464). As I have pointed out elsewhere (Roux 39), for Virgil, the representation, originally described as nova res oblata, a strange thing in Aeneas' s path, becomes completely internalised: the symbolic representation of the past is fully owned by Aeneas, who uses it to conceive of the possibility of a future. In De Man's words, we could say that he recognises in the symbolic mode of analogical correspondences an organic world that he is still a part of (222). Marlowe's Aeneas, however, sees only death and alienation in the past: if anything, he becomes the nova res, the strange thing that drops out of the picture and now has no proper place in the world. In Africa, the Other is Aeneas: the symbolic is an uncanny or 'unhomely' category that invokes the idea of self and location even as it places these categories under erasure. When Dido admonishes Aeneas to "remember who thou art" and to "speak like thyself (2.1.100), she is really asking him to identify with the signifiers that precede his arrival, to speak like Virgil's Aeneas. But in this Elizabethan retelling, Aeneas has gone missing. He has a name in the play, but the character seems inadequate to the name, always in some sense in surplus or a deficit to the symbolic that he is supposed to inhabit. The strangeness of the African shore serves really to dramatise Aeneas' estrangement from himself, his own status as a homeless stranger, a stranger even to his own signifiers, the very name that is supposed to carry Western civilisation. This, I would argue, is precisely the space in which the humanist subject is born: in this failed repetition of the past, a gap that opens in the classical world as it is re-told or re-imagined. Consider Pico Della Mirandola' s famous answer to the question "why is man such a wonderful creature?": [God] made man a creature of indeterminate and indifferent nature, and, placing him in the middle of the world, said to him 'Adam, we give you no fixed place to live, no form that is peculiar to you, nor any function that is yours alone. According to your desires and judgment, you will have and possess whatever place to live, whatever form, and whatever functions you yourself choose. All other things have a limited and fixed nature prescribed and bounded by our laws. You, with no limit or no bound, may choose for yourself the limits and bounds of your nature.' (Cassiner 224-25) The autonomous, self-authoring agent of Western humanism enjoys his power precisely because, in the first instance, he has no true nature, no fixed place and no determinate function. To stand apart from both nature and culture means that both world and language are sites of alienation; that the subject is at best imperfectly translated into lived situations, infinitely malleable because no signifier can arrest her subjectivity or bring it into full presence. There is a point of occlusion, a darkness where form collapses, that represents the shadow-side of the Western subject. Renaissance playwrights were fascinated by strangeness and Otherness at least partially because the autonomous self is predicated on destitution and estrangement, because a kind of strangeness had emerged at the centre of selfdefinition. Within Renaissance humanism, there is a busy engagement with the limits of humanism; a suspicion that "man isn't entirely in man", to echo Lacan (72), that serves as a counterpoint to accounts of the subject's uncircumscribed freedom. There is a strong philosophical tradition of skepticism in the Renaissance concerning the power of reason - from Petrarch, who claimed that "... what a man knows is nothing when compared ... with his own ignorance" (quoted in Cassiner 67), to Montaigne's foregrounding of the limitations of reason and sense: We have by the consultation and concurrence of our five senses formed one Verity, whereas peradventure there was required the accord and consent of eight or ten senses, and their contribution, to attaine a perspicuous insight of her, and see her in her true essence. (Montaigne [B] 310) In his discussion of Shakespeare's sonnets, Shakespeare 's Perjured Eye, Joel Fineman points out how the Dark Lady sonnet sequence introduces a certain undecidability to the poet's subjectivity: Instead of identifying himself with what is like himself, the poet instead identifies himself, not only with what is unlike himself, but what is unlike itself- 'By self-example mayest thou be denied'. As a result, but as a highly paradoxical result, no longer joined to a sameness which is the same as itself, the poet is joined instead to an irreducible difference, to an essential otherness, whose power consists in the way it thus disrupts the logic and erotics of unified identity and complimentary juncture. (Fineman 22) This finding of an "irreducible difference", both in the subject's identification with another and in the other itself, this point of pure desire, marks a limitation internal and essential to Renaissance humanist philosophy. Renaissance humanism is paradoxically split against itself, a celebration of the subject's freedom from restrictions and an anxious series of returns to the boundaries of the subject. To be absolutely clear, while this ambivalence plays a role in the erection of the 'self of humanist thought, it is particularly visible in the Renaissance. As much as the equivocation is constitutive of the Western notion of the autonomous self which emerges in the Early Modern period, it also threatens to undermine its persuasive power, because the oscillation between a discourse of triumph and a discourse of frustration undermines the idea of the 'self as a stable entity with a coherent purpose and specific formal attributes. Lynn White points out that with the introduction of the idea of progress in the seventeenth century, Renaissance humanism's self-reflexive reference to its own lack becomes restrained: John Donne's lament for a vanishing order - ' 'Tis all in peeces, all cohearance gone' succumbed to the vision of mankind's perfectibility. The idea of progress had vast therapeutic value because it enabled most people to maintain personal psychic stability in the fece of an ever increasing cultural velocity. Its advent marks the end of the Renaissance because it notably reduced the quantum of anxiety which had been the most characteristic feature of Western society in that age. (White 45-46) In summary, the subject of humanism has a considerable investment in the unformed, the negative, the unarticulated. Aeneas' s hysterical, passive distance from the forms in which he is represented is a symptom of this investment. The resonances with Othello are obvious: Othello is an alien in an alien world, precariously holding onto an identity that is incessantly undercut by and eventually supplanted by a racist construction of what it means to be a Moor. The play demonstrates both the power of the signifier and its arbitrariness. Our sympathy for Othello is enjoined by precisely that sense that there is more to him than even his selfdescription would suggest, an ineffable tragic remainder that cannot be expressed but that is also the repository of his humanity. Is this not exactly the illusion that many postcolonial critics of the play are deceived by, and is this not the fundamental illusion that enables subjectivisation, the erection of the autonomous self of humanism and the Enlightenment? In other words, despite the obvious transformations of the idea of the "self since the Renaissance, the underpinning belief in a private, agented self, in excess of its public roles, remains pivotal to the broad historical sweep that we have termed "modernity". In this sense, Desdemona's frequently discussed handkerchief serves to embody the gap between the signifier and the world: Iago cleverly uses it to provide the kind of ocular 'evidence' that Othello requires of Desdemona's unfaithfulness, dramatically demonstrating the contingent and constructed nature of apparently self-evident reality. Othello's crime is that he mistakes the sign for the thing itself, and in the process collapses his own identity into the signs that manufacture him as Moor: jealous, intemperate, murderous, barbaric. The handkerchief, poised somewhere between the world of things and the world of words, serves to link stories to reality even as it reminds the authence that the link is ultimately false, that language opens up a gap, and that without the gap there is no subjectivity or autonomy. In Marlowe's Dido, Queen of Carthage, Aeneas sails into history while Dido immolates herself on a pyre made of his relics. In a sense, Aeneas rejoins Virgil's epic at this point, after his detour through the English Renaissance: a return that is eloquently (and for some critics, puzzlingly) signaled by Dido's adoption of Virgil's untranslated Latin lines in the closing scene. However, Marlowe's play returns Aeneas to the world of classical antiquity with a typically Renaissance sense of undecidability, a dissonance between the name and the referent that opens the space for the subject of modernity. A broad range of readings of Othello produce a similar dissonance, which I am claiming is an essential component of humanist thought. If we read the play as a narrative about an honorable soldier and statesman who is overpowered by the semi-intemalised racist ideology of his time, then the suggestion is that even a central and respected figure, in every way identified with the cosmopolitan values of the Renaissance city state, is haunted by Otherness: he can never take his place in the symbolic for granted because there is an excess to his subjectivity that constantly threatens to erase the public identity that he performs: "a monster in his thought", to use Othello's own words, "too hideous to be shown" (3.3:111-112). When Lodovico encounters the tormented Othello of the fourth act, he asks: "Is this the noble Moor, whom our full senate/Call all in all sufficient?" (4.1:260-261), the answer is of course that it is not - the noble Moor has been supplanted by an Other, he is divided against himself and alienated from his symbolic identity. If, in contrast, we read the play as essentially a racist fantasy that claims even a noble, Christian Moor will eventually succumb to the Elizabethan stereotypes that define and dismiss blackness, then Othello's tragic grandeur and obvious victimisation interpose between the racist nomination and its referent. It is entirely possible that the play simply returns Othello to his stereotype in order to foreclose the possibility of black agency in a European world, but the return to the stereotype is indelibly marked by a troubling excess and ambiguity, the possibility that Othello's signifiers describe him even as they expunge him. In either reading, Othello is both more than and less than the language in which he is couched; he is defined through a kind of surplus-deficit that is also at the very heart of his prominent mutability. In other words, Othello's Otherness really describes or invokes a sense of self-estrangement essential to the humanist notion that the subject cannot be reduced to his place in culture or to the signifiers through which she is made present to others. The so-called 'unified self of modernity is born in this gesture of self-alienation, a kind of aesthetic and philosophic certainty that there is something in the self that is more than or other than the self, a homeless, deracinated kernel that escapes all attempts to name it and essentially places the subject on a profoundly individual and interiorised path. There can be no fantasy of individual autonomy without such a concomitant fantasy of alienation from culture. Moreover, the fantasy of alienation and estrangement is not in itself subversive of social orthodoxy, or even at war with the notion of the unified subject. In Radical Tragedy, Jonathan Dollimore seems seduced by the idea that any critique of the plenitude and coherence of the autonomous subject must be an act of subversion. Dollimore quotes from Montaigne's first book of essays in order to show how Montaigne has an Althusserian understanding of ideology "as so powerfully internalised in consciousness that it results in misrecognition" (Dollimore 17). For instance, Montaigne writes: "The lawes of conscience, which we say to proceed from nature, rise and proceed by custome" (quoted in Dollimore 17). According to Dollimore, Montaigne therefore displays a radical understanding of how the subject is constructed in ideology; how the subject assumes as his own the demands of the symbolic. However, in his chapter "Of Custome, and How a Received Law Should not Easily be Changed", Montaigne follows his exposé of the insidious operation of custom with ruminations on the virtue of following custom, and the dangers of challenging authority: "Those which attempt to shake any Estate, are commonly the first overthrown by the fall of it" (Montaigne [A] 119). The man of reason, while acknowledging society's faults and inadequacies, nonetheless behaves in a thoroughly orthodox manner - his difference to society is a "private fantasie" (121): [M] an ought inwardly to retire his minde from the common presse and hold the same liberty and power to judge freely of all things, but for outward matters, he ought absolutely to follow the fashions and forme customarily received. (118) In other words, the humanist subject maintains a sense of difference, of interior freedom, of detachment from the social, by maintaining the social order. The gap, the fault, in which society loses its 'belonging to me' aspect, is visible only against the backdrop of orthodoxy. The lack in the symbolic is visible only 'inside' the symbolic order; it is only from within the symbolic order itself that the subject acquires its sublimated traumatic existence and thereby retroactively locates itself. The 'rational' subject is constructed through the perception and maintenance of the 'lie' of custom, a point Dollimore seems to avoid. Montaigne's argument for orthodoxy follows a circular route. The subject possesses a subjective, rational freedom that exists independently from ideology, and is therefore in a position to pose questions about ideology. Simultaneously, the subject finds a place in culture that is defined by the very (ideological) signifier the private self is alienated from. Challenging the legitimacy of the signifier one is attached to dissolves the peace and privacy that allows one the freedom to recognise the signifier as alien ... Montaigne is, in other words, an advocate for passivity and a certain kind of conservatism. To conclude, then: postcolonialism offers a convincing account of Othello in terms of selfestrangement, hybridity, cultural translation and so on. However, we should entertain the possibility that Othello works so well as a postcolonial text because postcolonialism draws so many of its terms and preoccupations from a dialectical understanding of humanist subjectivity that became prominent in the Early Modern moment in Europe. In other words, it is actually Othello that offers the reading of postcolonialism. Again, postcolonialism' s deployment of its central tropes is not per se misleading or politically ineffectual, in part at least because postcolonial predicaments are intimately entangled with Western predicaments. But they are not new, nor are they specific to a 'non- Western' point of view, or even powerfully at odds with Western notions of the subject as a stable, unified category. In fact, they need to be translated to new epistemological contexts - which is perhaps why Achille Mbembe, to the dismay of some critics, has dimissed what he calls "Foucauldian, neo-Gramscian paradigms" that "problematize everything in terms of how identities are 'invented,' 'hybrid,' 'fluid,' and 'negotiated'" (5). Mbembe' s own work evidences that he has in fact not rejected the notion of identity construction or plasticity. It is the paradigm that is questioned: its apparently unassailable status in some postcolonial thinking and its history of investiture in the same Western modes of thought that produced colonialism. [Footnote] NOTES 1. See Ben Okri's "Leaping out of Shakespeare's Terror" in A Way of Being Free (71-87). Okri concludes that while Shakespeare's play opens a space for blackness on the English stage, Othello continues to be "white underneath" (74). 2. Based on a reading and discussion with Caryl Phillips at "Try Freedom", a conference of the European Association for Commonwealth Language and Literature Studies (EACLALS) in Venice in 2008. 3. See, for instance, Shakespeare and Race, edited by Catherine Alexander and Stanley Wells, Ania Loomba's Shakespeare, Race and Colonialism and Jonathan Burton's "A Most Wily Bird" in PostColonial Shakespeares. 4. The incident is described in Stendhal's Racine et Shakespeare, published in 1823. Wesley Bird notes, however, that Stendhal might have invented, exaggerated or transposed the incident, because Baltimore's two theatres were closed in August 1822 (Bird 118-119). 5. Steane, for instance, thinks Marlowe might have been in "too much of a hurry" (48); Levin feels Marlowe is being evasive (33); while Gill proposes the rather unlikely possibility that Marlowe was "modest" and "knew where he could not hope to excel" (153). 6. See, for instance, Jeremy Weate's "Achille Mbembe and the Postcolony: Going beyond the Text". [Reference] WORKS CITED Alexander, Catherine and Stanley Wells, eds. Shakespeare and Race. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2000. Bird, C Wesley. "Stendhal's Baltimore Incident: A Correction". Modern Language Notes 61.2 (1946): 11819. Burton, Jonathan. "A most wily bird': Leo Africanus, Othello and the Trafficking in Difference". PostColonial Shakespeares. Eds Ania Loomba and Martin Orkin. London: Routledge, 1998. Cassiner, Ernst et al, eds. The Renaissance Philosophy of Man. Chicago: Chicago University Press, 1965. De Man, Paul. Blindness and Insight: Essays in the Rhetoric of Contemporary Criticism. Second Edition. New York: Routledge, 1983. Fanon, Frantz. Black Skin White Masks. Trans. Charles Lam Markmann. St. Albans, Hertfordshire: Paladin, 1973 [1952]. Fineman, Joel. Shakespeare 's Perjured Eye: The Invention of Poetic Subjectivity in the Sonnets. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1986. Gill, Roma. "Marlowe's Virgil: Dido Queene of Carthage'. The Review of English Studies 28.110 (1977): 141-155. Lacan, Jacques. The Seminar of Jacques Lacan: Book 2: The Ego in Freud's Theory and in the Technique of Psychoanalysis 1954-1955. Ed. Jacques-Alain Miller. Trans. Sylvana Tomaselli. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1988. Levin, Harry. The Overreacher: A Study of Christopher Marlowe. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1952. Loomba, Ania. Gender, Race and Renaissance Drama. Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1989. _____ . Shakespeare, Race and Colonialism. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2002. Marlowe, Christopher. The Complete Plays. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1986. Mbembe, Achille. On the Postcolony. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2001. Montaigne. [A] Essays: Volume One. Trans. John Florio. London: JM Dent & Sons, 1980 [1580]. _____ .[B] Essays: Volume Two. Trans. John Florio. London: JM Dent & Sons, 1980 [1580]. Okri, Ben. "Leaping out of Shakespeare's Terror." ,4 Way of Being Free. London: Phoenix House, 1998: 71-87. Phillips, Caryl. '"Rude am I in my speech': A Reading and Conversation with Caryl Phillips". EACLALS Try Freedom: Rewriting Rights in/through Postcolonial Cultures Conference. Venice, Italy, 29 March 2008. Roux, Daniel. '"Well may I view her, but she sees not me': The Subject and the Invisible in Marlowe's Dido, Queen of Carthage." The Southern African Journal of Mediaeval and Renaissance Studies 9.1 (1999): 35-44. Shakespeare, William. Othello. Ed. FCH Rumboll. Stratford Series. Cape Town: Maskew Miller Longman, 1996 [c.1604]. Steane, J.B. Marlowe: A Critical Study. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1964. Stendhal. Racine et Shakespeare. Paris: JJ Pauvert, 1965 [1823]. Weate, Jeremy. "Achille Mbembe and the Postcolony: Going beyond the Text". Research in African Literatures 34.4 (2003): 27-41. White, Lynn. "Death and the Devil". In Robert S. Kinsman (ed.) The Darker Vision of the Renaissance: Beyond the Fields of Reason. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1974. Young, Robert. Colonial Desire: Hybridity in Theory, Culture and Race. London: Routledge, 1995. [Author Affiliation] Daniel Roux is a lecturer in the English Department at the University of Stellenbosch. His current research focuses on writing from and about South African prisons. His interest in some of the current debates in postcolonial theory led him back to Othello. Indexing (document details) Author(s): Daniel Roux Author Affiliation: Daniel Roux is a lecturer in the English Department at the University of Stellenbosch. His current research focuses on writing from and about South African prisons. His interest in some of the current debates in postcolonial theory led him back to Othello. Document types: General Information Publication title: Shakespeare in Southern Africa. Grahamstown: 2009. Vol. 21 pg. 23, 8 pgs Source type: Periodical ISSN: 1011582X ProQuest document ID: 1909427251 Text Word Count 4618 Document URL: http://proquest.umi.com.ezproxy1.library.arizona.edu/pqdweb?did=0000001909427251&Fmt=3&cl ientId=43168&RQT=309&VName=PQD Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction or distribution is prohibited without permission.