The assessment of risks associated with Government investment

advertisement

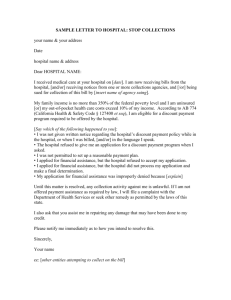

GOVERNMENT INVESTMENT DECISIONS, PRIVATISATION AND THE APPROPRIATE DISCOUNT RATE Michael C. Crowley School of Commerce Flinders University of South Australia GPO Box 2100 Adelaide, South Australia 5001 Telephone: +61 8 8201 2882 Facsimile: +61 8 8201 2644 Email: Michael.Crowley@flinders.edu.au SCHOOL OF COMMERCE RESEARCH PAPER SERIES: 00-20 ISSN: 1441-3906 Page 1 of 27 GOVERNMENT INVESTMENT DECISIONS, PRIVATISATION AND THE APPROPRIATE DISCOUNT RATE Page 2 of 27 ABSTRACT This paper enlarges upon the debate regarding the impact on the assessment of risks in regard to Government investment decisions, by focussing on its significance in the privatisation of Government assets. Previous papers focus on two possible outcomes in the assessment of Government investment risk1. Firstly, Government risk associated with investment decisions is the same as for the private sector, therefore, it should be discounted in the same way as the private sector. Secondly, investment risk is lower for the Government than it is for the private sector, therefore, the discount rate used for Government should be lower than the discount rate used for the private sector. This paper expands on a third possible alternative; that the risk associated with Government investment decisions are different to that of the private sector, however, this difference could lead to the discount rate for Government that is evaluated to be higher than that assessed for the private sector. It is acknowledged that the three possible alternative discount rate scenarios can lead to very different investment decisions when assessing the privatisation options for Government. The paper concludes by proposing suitable methods for measuring the appropriate discount rate for Government investment decisions in privatisation. It is suggested that using either multi-factor Capital Asset Pricing Model (CAPM) or multi-factor models via analysing and pricing individual risk factors can provide the most accurate measurement of risk. KEY WORDS: – Discount rate, Privatisation, Risk, Government risk, Risk-free rate, Risk factors. Investment risk factors. 1 See Samuelson, P. A. (1964), Vickrey, W. (1964), Arrow, K. (1965, 1966), Arrow, K. and Lind, R. (1970), and Bailey, M. and Jensen, M. (1972). Page 3 of 27 1.0 INTRODUCTION The assessment of risks associated with Government investment decisions has always raised considerable controversy2. Government investment decisions have attracted more attention over the last two decades with the increase in Privatisations worldwide3. The proceeds from privatisation in Australia have totalled in excess of $70 billion4. By international standards, Australia’s privatisation program has been extensive. In terms of dollars netted it runs second in the OECD after the UK, while relative to economic size it is also second, but this time to New Zealand5. Therefore, Government investment decisions through their impact on privatisation have been extremely important to Australia. A Government investment decision, like any private capital market investment decision, is to maximise the present value of returns properly adjusted for risk6. Therefore, the Government, like any other investor, will base its investment decision around its ability to maximise expected value from its assets. In assessing potential investment options through privatisation an important factor for Government to consider is whether the value of an asset is maximised with Government ownership or private sector ownership. Thus, the Government has the option to maximise the value of an asset by maintaining Government ownership or through a sale of the asset to the private sector. Should the value of an asset be different, if held by the Government or the private sector, remains controversial. The assessment of risk when determining this value is where there is particular contention amongst academics. The assessment of 2 See Samuelson, P. A. (1964), Vickrey, W. (1964), Arrow, K. (1965, 1966), Arrow, K. and Lind, R. (1970), and Bailey, M. and Jensen, M. (1972). 3 For a synopis on the history of privatisation see: Waterman, E, (1993), in Davis, K. and Harper, I (eds.), “Privatisation: The Financial Implications”, Allen and Unwin, p. 23. 4 Munckon, P. (April 2000, pp. 60 – 61). 5 Munckon, P. (April 2000, pp. 60 – 61). 6 While it is debatable that Government investment decisions are based on the prime objective to maximise expected value it is generally accepted that this is a reasonable assumption when assessing privatisation options. See Vickers, J. and Yarrow, G. (1988). Page 4 of 27 investment risk has the capacity to affect the determination of the discount rate used in investment decisions. Government investment decisions, particularly privatisation investment decisions, are no exception to this. Thus, accurately determining an appropriate discount rate is critical when considering the Privatisation of a Government owned asset. Previous debate on Government investment risk, and its effect on the discount rate to be used, has focussed on two possible outcomes. Firstly, Government risk associated with investment decisions is the same as for the private sector, therefore, it should be discounted in the same way as the private sector. Thus, it is irrelevant if the Government or private sector owns the asset7. Secondly, investment risk is lower for the Government than it is for the private sector, therefore, the discount rate used for Government should be lower than the discount rate used for the private sector. This argument therefore provides for the option of two different values for the same asset, one, higher, value if retained by Government and another, lower, value if privatised. A third possible alternative that has not been seriously considered in the academic debate is that the risk associated with Government investment decisions are different to that of the private sector. However, this difference is that risk is assessed to be higher for Government ownership than private sector ownership. This, in turn could lead to a discount rate for Government that is evaluated to be higher than that assessed for the private sector. Therefore, the value of an asset may possibly be higher with private sector ownership than Government ownership. Thus the assessment of investment risk in three ways provides for the use of different discount rate determination. Using different discount rates could lead to very different investment decisions when assessing the privatisation options for Government. Section 2 of the paper discusses the importance of investment risk assessment in the privatisation process. The paper continues in Section 3 by focussing on previous 7 This assumes that the cash-flow is the same for the asset if it is Government or private sector owned. Page 5 of 27 investment risk arguments. Section 4 expands on the debate by discussing a third possible alternative, that risk, and therefore the discount rate, could be higher for the Government than for the private sector. The paper concludes in Section 5 by proposing suitable methods for measuring the appropriate discount rate for Government investment decisions in privatisation. It is suggested that using either multi-factor CAPM or multi-factor models via analysing and pricing individual investment risk factors can provide a more accurate measurement of risk which, in turn, will lead to the use of a more accurate discount rate. 2.0 GOVERNMENT AND PRIVATE SECTOR OWNERSHIP: OBJECTIVES, INVESTMENT APPRAISAL AND PRICING. The prevailing ideologies behind public verses private investment decisions differ dramatically. Governments undertake investment decisions for a variety of reasons. They seek to promote equity by aiding the poor and the disadvantaged and they provide a variety of services, such as education, health, defence, infrastructure, police and postal services. Thus, these investment decisions relate to economic, social, and political objectives. These objectives may themselves vary considerably over time as Governments change or political priorities alter. Frequently changing objectives of course create confusion, indeed, how to determine the benefits of these investment decisions in this environment is open to much controversy. On the other hand, while there may also be multiple objectives in private sector investment decisions they can be united under a broadly defined, but generally accepted, objective of wealth maximisation. Although the actions involved to achieve this objective may be complex, the objective itself is well defined and unchanging, and it has a clear observable measurement indicator of performance, namely the stock market or share price. This contrasts sharply with the often confused and conflicting multiple objectives, and subsequent measurement, for Government investment decisions. Likewise, the objectives for the privatisation process itself can be just as diverse as any other Government investment decision. For example, the objectives for Page 6 of 27 privatisation around the world have varied. Many Governments view privatisation as the solution to resolving all the problems of Government owned enterprises. While no one has defined a comprehensive list of objectives, ranked by priority or weight for privatisation, Vickers and Yarrow (1988) list what they believe to have been the principal objectives of privatisation; 1. improving efficiency; 2. reducing the public sector borrowing requirement; 3. easing problems of public sector pay determination; 4. reducing government involvement in enterprise decision making; 5. widening ownership of economic assets; 6. encouraging employee ownership of shares in their companies; and 7. redistributing income and wealth. However, while the objectives for privatisation may be many and varied, it is generally accepted that the fiscal objective for privatisation is quite clear-cut8. That is, to maximise shareholders/taxpayers wealth. This objective has a measurable counterpart in the private sector. The basic problem in pricing Government investment decisions is having to price something that has never existed in the commercial world. This pricing involves having to uncover and value the effects of Government investment risk. From a modern finance view of the world it is generally accepted that private sector investment decisions and the subsequent contribution to shareholders wealth is done by discounting an investments expected cash flows back to a present value using a risk adjusted discount. A process known as discounted cash flow (DCF) analysis. An adaptation of the DCF analysis is shown in Figure 1 9. This model provides a framework for privatisation pricing. The model shows valuation as a process of determining the future free cash flow of the asset facing privatisation. In this model, value is based upon future free cash flow, which is discounted back to a present value 8 9 A review of these objectives is outside the scope of this paper. Lawriwsky, M. and Kiefel, C. (1993, p. 45) Page 7 of 27 using a discount rate that reflects the business and financial risk of the enterprise. The main elements of value in the model are cash flow, growth in cash flow and risk. The latter element, investment risk, is usually built into the discount rate used to value the assets to be privatised. It is this issue that this paper considers, recognising that much of the previous debate over privatisation has focused on the former elements, in particular, the cash flow growth generated by efficiency gains. A Framework for Assessing Investment Risk Government Regulation Assumptions Income Statement Funds Statement CPI – X or Rate of Return Balance Sheet Entry Conditions Free Cash Flow Financial Risk Discount Rate Business Risk Valuation Sale Scenarios Source: Lawriwsky and Kiefel (1993, p. 45.) Government Receipts FIGURE 1. Page 8 of 27 Not only can Figure 1 be used as a framework for privatisation analysis, it can also be used as a platform for discussing the main factors creating investment risk in Government investment decisions. The recent focus on Privatisations worldwide have brought attention to these issues and other associated topics such as; which assets should be owned by the public sector, whether assets have different values in the public and private sectors and how to price assets that are transferred between the two sectors. The crux of each of these questions is critical on the correct determination of investment risk. In Australia, with the exception of Grant and Quiggin (1999), Klein (1997), Quiggin and Officer (1999), the debate on the assessment of risk used in the discount rate in assessing privatisation options has been scarce. Thus, Government investment decisions relating privatisation to the valuation or pricing of the assets has been paramount. 3.0 THE INVESTMENT RISK ADJUSTED DISCOUNT RATE Debate over the appropriate discount rate to use for Government investment decisions dates back to the 1970s when the issue was one of deciding the appropriate rate to be used in evaluating Government investment projects. In determining this discount rate a number of different opinions have been put forward: I. the private rate, reflecting current market saving, investment and consumption preferences10, II. the social rate which corrects for the market’s “faulty telescope”11, III. the opportunity cost or rate of return forgone by private sector investments displaced by public sector ones at the margin12. 10 One discount rate that could be used in Government investment evaluations is the market rate of interest. Under limiting assumptions, the use of the market rate of interest would lead to an efficient allocation of financial resources between competing public and private sector investment proposals. 11 It has been claimed that people systematically undervalue future incomes and overvalue the present. That is, individuals’ consumption decisions are biased in favour of current consumption due to heavy discounting of the benefits of savings and investment for the future. Such myopia is what Pigou termed the “faulty telescope”. Individuals underestimate the importance of saving and overestimate that of current consumption. Overall it is argued that the private rate is too high since consumer’s time discount is too high, hence Governments should intervene to correct the error by applying a lower rate. Page 9 of 27 The discount rate used in assessing privatisation investment alternatives is critical in that it has a direct bearing on whether the Government should maintain the ownership of an asset or privatise it. A central question is whether the discount rate used in this assessment should reflect a discount rate that is applicable to Government investment decisions, or a discount rate that is applicable to private sector investment decisions. Conceptually, if the risk associated with the discount rate is different for Government investment decisions than it is for private sector investment decisions, ceteris paribus, free cash flow then as a matter of pure valuation mechanics will be valued differently for the Government and the Private sector. For example, if capital employed by the Government has a lower assessed investment risk than that of the private sector then assets will be more valuable if retained by Government13. The outcome would suggest that, at least in part, privatisation programmes are erroneous. In the history of this debate the following issues in assessing Government investment risk are briefly discussed. 3.1 POOLING OF PUBLIC PROJECTS Early Overseas support for the use of a lower Government discount rate when evaluating Government investment decisions proposed the use of a risk-free discount rate14. The basis of their arguments focused on the proposition that the risk associated with a particular public venture is inevitably pooled and averaged along with the risks of other projects, and this pooling or averaging of risk for public projects is accomplished without any cost of extra financial transactions. Contrary to this line of thinking, it could be argued that pooling reduces risk only if the outcomes of Government assets are independent both of each other and of outcomes of private investments. The vast majority of Government projects will have 12 The concept of opportunity cost, most relevant to private sector investment decisions, must also be considered in public sector investment decisions. It must be recognised that there may be an opportunity cost involved in diverting funds from the private sector to allow for public investment. This opportunity cost must be recognised in public investment decisions to ensure that resources are allocated efficiently with the aim of maximising the economy’s wealth. 13 This ignores any potential gains in value from operating efficiency improvements post privatisation. Page 10 of 27 outcomes correlated with national income15. For instance, Government projects, such as highways, electrical power etc., that facilitate commerce will produce greater benefits when national income is high than when it is low. To this end it cannot be considered that covariance between Government assets does not exist and therefore Government risk cannot be diversified away to zero. In addition, the private sector and individual investors can also pool risks. Any advantage that Government may have in pooling diverse risks could be transferred to the private sector or to private investors. Accordingly, risk affects Government and non-Government entities equally. Therefore, according to this argument Government and private sector investment risks are assessed to be equal. 3.2 THE LAW OF LARGE NUMBERS A corollary to the argument that ‘pooling of public projects’ leads to the elimination of Government investment risk is the notion that the Government has the ability to spread risk associated with a public investment among a large number of people so that the ‘total’ cost of risk-bearing for an investment is insignificant16. As the number of investors, or in this case, taxpayers, becomes large the total cost of risk-bearing approaches zero17. Crucial to this argument is the Government’s ability to draw on a large number of taxpayers so that the level of investment with respect to the total wealth of each taxpayer is only small. It is argued that the private sector on the other hand does not enjoy the same ability to spread risks. Some shareholders, in order to control a firm, may hold a large stock of shares that represent a significant part of their wealth. Once again a contrary view could be expressed. Why could not large corporations achieve the same result? For instance, modern finance theory is based upon the premise that markets will not reward investors who fail to hold an efficient portfolio, 14 15 16 See Samuelson, P. A. (1964), Vickrey, W. (1964) Arrow, K. (1965, 1966) and Arrow, K. and Lind, R. (1970). Bailey, M. and Jensen, M. (1972, p. 274). Arrow, K. and Lind, R. (1970). Page 11 of 27 and therefore, large block shareholders are expected to hold a diversified portfolio like any other investor. Also, in some cases the major shareholder could be an equity fund consisting itself of many shareholders, thus spreading the costs of risk-bearing over an even greater number of shareholders. Also, does it necessarily follow that risk, if spread over many investors, will reduce investment risk for a Government asset without changing the outcomes of the distribution of these risks that are connected with the benefits related to the use of the asset18. Similarly, although the cost is spread over the general population of taxpayers, this is not to say that the relative stake for each taxpayer is so insignificant as to change their attitudes towards risk. What is relevant here is whether the costs and benefits at stake for each household is considered small enough by them not to change their risk preferences. In addition, the benefits and costs of Government assets are generally captured by particular private households rather than the population in general, and therefore, it is the portfolio risk of those particular households that is relevant and not that of the Government. To the extent the risks associated with an asset that benefits only one part of the community are spread over the nation as a whole then the investment risk may become greater than private risk19. Similarly, distributing risks to individuals on the basis of each individuals share of the total tax liability is unlikely to be optimal since someone with a large share of the tax liability might be highly risk averse. Thus, Government assets of given risk have a greater problem of finding their way to the right portfolios than do similar private projects and may, if anything, command a higher risk premium20. 17 In this discussion on Government investment risk it is assumed that taxpayers act in the same manner, assume the same functions, rights and obligations as investors in the private sector. 18 Bailey, M. and Jensen, M. ( 1970, p. 272). 19 Bailey, M. and Jensen, M. (1970, p. 276). 20 Bailey, M. and Jensen, M. (1970, p. 281). Page 12 of 27 3.3 AGENCY RISKS It is argued that in the private sector it may be in the interest of managers, when considering their careers and income are dependent upon firm performance, not to make decisions that assist the firms wealth maximising objective. It is hypothesised these managers will make investment decisions that are of low risk. These decisions may not be the most optimal decisions for the firm. This implies that a lower discount rate should be applied to Government owned assets. However, it can also be argued that bureaucratic managers themselves may be just as risk averse and reluctant to make risky investment decisions as are corporate managers for exactly the same reasons21. 3.4 UNAVOIDABLE RISKS Many risks are unavoidable to the private investor and corporation, which simply do not exist for the Government sector. The only avoidable risks that are unavoidable to Government are risks in the class of atomic bomb treaties which need strong discounting for risk dispersion22. However, proponents of this view do not name the risks that are avoidable to Government and not the private sector, except insurance23. Against this view is the argument that the risks that are unique to Government may be larger than estimated. 3.5 TAX AND MONOPOLY POWER It has been argued that given the Government’s relative imperviousness to financial distress and its effective monopoly in the provision of many services it is insulated from risk. Unlike private-sector firms, the Government can often tax its way out of financial difficulties. However, contrary to this view is the argument that the Government is therefore not unlike a firm that has large discretionary cash flows. 21 Klein, M. (1997, p. 6). Samuelson, P. A. (1964), and Grant, S. and Quiggin, J. (1999). 23 Samuelson, P. A. (1964). 22 Page 13 of 27 Also, the argument ignores the political costs of increasing taxes especially if the tax increase is needed to pay for a failed Government commercial venture. 3.6 THE DISCOUNT RATE SHOULD REFLECT THE RISK-FREE RATE It is often proposed that the Government discount rate should reflect the risk-free rate. This argument is based on the premise that the Government can borrow at the riskfree rate while the private-sector firms generally borrow at a higher rate of interest. More importantly, the private sector must service equity which is made more costly by the risk premium that must be paid to shareholders. However, this position ignores the fact that taxpayers bear the residual risk of Government investment in much the same way that as shareholders of a private-sector firm. Once again political costs increase with Government debt levels. Also, the cost of debt to a private sector firm is tax deductible24. In addition, the risk-free rate reflects the cost at which Government can borrow rather than the risk attached to the expected cash flows of the assets themselves. By virtue of Government guarantee the cost of debt to Government is low. However, it is not clear that cash flows relating to Government assets will enjoy the same level of certainty. 3.7 CAPITAL MARKET IMPERFECTIONS AND THE EQUITY PREMIUM PUZZLE A justification for a lower discount rate for Government owned assets have been based on the ‘equity premium puzzle’. It is argued that if the ‘equity premium puzzle’, which describes the discrepancy between the observed and predicted equity premium, is the result of capital market imperfections, then the appropriate discount rate for the Government is that which would be generated by a perfect capital market25. However, there is little reason for supporting this position. Firstly, the existence of the equity premium puzzle is not necessarily to make the argument that Governments 24 25 Brealey, R. A. et. al. (1997, p. 9). Officer, R. R. and Quiggin, J. (1999). Page 14 of 27 have a preferential access to capital markets relative to the private sector26. Secondly, there is little reason to believe that market imperfections do not apply equally for Government sector investments as for private sector investments. The assertion that there is no moral hazard in Government is based on the belief that fraudulent behaviour of managers and associates does not happen in the public sector. In fact the monitoring costs in the Government sector, including Government auditors, supervisory boards, parliament and its committees and overall, the electorate, may in fact be higher. 4.0 A HIGHER RISK ADJUSTED DISCOUNT RATE FOR GOVERNMENT INVESTMENTS Previous debate on the discount rate appropriate for Government investment risk assessment, as noted in section 3, provides two possible alternatives. Firstly, Government risk associated with investment decisions is the same as for the private sector, therefore, it should be discounted in the same way as the private sector. Based on this investment risk assessment, ceteris paribus, it does not matter if assets are Government owned or privatised. Secondly, investment risk is lower for the Government than it is for the private sector, therefore, the discount rate used for Government should be lower than the discount rate used for the private sector. This implies the option of two different values for the same asset, one, higher, value if retained by Government and another, lower, value if privatised. Therefore, assets should remain in the hands of Government. What has been largely omitted in previous debate on the appropriate investment risk for Government decision making is the possibility that the discount rate for Government is different, however, this time investment risk will be greater for Government than that for the private sector. In the absence of efficiency gains this would suggest that many, if not all, Government owned assets should be privatised. The development of risk measurement models such as multi-factor C.A.P.M., Arbitrage Pricing Theory (APT) and associated multi-factor models has expanded the 26 Officer, R. R. and Quiggin, J. (1999, p.12). Page 15 of 27 mechanisms used for examining investor risk and pricing of individual risk factors. Use of these mechanisms, together with careful development in identifying potential investment risk factors, provides the ability for developing an argument that investment risk could be higher for Government by focussing on specific risk factors. Few studies have attempted to identify and rigorously test individual risk factors associated with Government investment risk that have the potential to increase the discount rate for Government owned assets27. However, previous debate, briefly alludes to some possible factors. Bailey and Jensen in their 1972 article argue that the efficient allocation of risk bearing is usually more difficult for Government investments than it is for private investment. Therefore, if anything, the allowance for risk should be greater for Government investments than it is for otherwise comparable private investments28. In their discussion they offer specific arguments on various broadly defined risk factors involved in Government investments, based on “market imperfection” and “distribution problem” issues. They propose that these risk factors could cause Government investment assessed risk to be higher than the private sector. Research into mixed firms (firms that have both Government and private owners) identify possible investment risk factors that are present in both the Government and the private sector. However, with Government ownership these factors are hypothesised to be more sensitive. A greater sensitivity to these factors would ensure the use of a higher discount rate for Government asset valuation. These noted factors appear to be either investment risk factors that exist in the Government sector but not in the private sector, or investment risk factors that exist in the both sectors, however the sensitivities of each sector to these factors are different. There could be numerous investment risk factors that affect Government ownership of assets. Therefore, a comprehensive discussion of these factors is beyond the scope of this paper. Hence, this paper will discuss two hypothesised potential risk factors. 27 28 In comparison to the same asset in the private sector. Bailey, M. and Jensen, M. (1972, p.269). Page 16 of 27 Firstly, an argument that non-marketability of assets is a risk factor that exists in the assessment of Government investment risk but not necessarily in private sector risk assessment. Secondly, that Government regulation risk factors are present in both sectors but are more sensitive with Government ownership. 4.1 NON-MARKETABLE ASSET In measuring investment risk it is normally assumed that assets are marketable and that investors are able to re-balance their portfolios according to their own risk preferences. Thus, if an investor does not consider the portfolio to be optimal they can change, without too much inconvenience, the assets within the portfolio to suit their risk-return profile. However, when relaxing the assumption of asset marketability, investors can no longer rely on the ability to re-balance their portfolios. Instead considerable risk is incurred with ownership of these assets and this represents a real cost to the investor who is then forced to hold a portfolio they consider to be sub-optimal. Examples of investors portfolios that could possibly contain non-marketable assets in the private sector are claims on future social security payments29. This definition of non-marketability includes assets that are normally marketable assets but are considered “fixed” in some investors portfolios. For example, investors may not readily market their homes in order to re-balance their portfolios, and therefore, their homes can be considered as a ‘fixed’ investment. This is due, not only to large transaction costs but also because of non-monetary factors30. While the reason for an asset’s non-marketability may be non-monetary it does not prevent it having the effect of increasing the risk profile of the existing portfolio of assets. It is important to consider non-marketability of assets as an additional investment risk to investors. With the existence of non-marketable assets locked into an investor’s 29 30 Elton, E. J, and. Gruber M. J., (1995, pp. 324 - 325). Non-monetary factors are factors considered by an investor when choosing their optimal portfolio that are determined for reasons other than its monetary impact on the portfolio. For example, an investor may not consider selling certain shares in their portfolio because they like the company’s name. They realise that this decision may not be financially optimal in the long term. Page 17 of 27 portfolio, the investor’s portfolio can be considered as sub-optimal, that is, there is a portfolio of alternative assets that is more efficient and provides a greater return for a given level of risk. While it is possible that the existence of non-marketable assets within the portfolio may still provide the most efficient risk-return trade-off, the risk-return profile of the portfolio may be different than that required by the investor. For example, the investor may be very risk adverse, and therefore, their optimal portfolio would be a portfolio that contains assets with low risk. However, the existence of non-marketable assets within the portfolio may cause the most efficient risk-return trade-off to be high risk. When the existence of non-marketable assets is considered the ‘efficient market portfolio’ will be different to that derived under the assumptions of tradeable assets and may lead to an incorrect trade off between risk and return. Thus, non-marketable assets represent an additional investment risk to investors as the expected return on the level of risk is now understated. Just as the individual investor may have non-marketable assets contained within their portfolio, it is logical to assume that the Government may also have non-marketable assets in its portfolio. For example, the Government has non-marketable assets that it will not consider or cannot consider divesting, for political reasons, and therefore is unable to achieve a desired optimal risk-return trade-off31. This, in turn, will increase its discount rate (investment risk premium). The degree and size with which the assets within the Government’s portfolio are non-marketable will determine the risk premium and discount rate to be used32. This also has implications for the discount 31 The change in Government assets in the areas of education, defence and health are relatively small from year to year. This can be due to two reasons. Firstly, the portfolio of assets is considered optimal and the change in this optimal portfolio requires little yearly change. Secondly, as stated above the Government’s portfolio of assets are sub-optimal but for political reasons the Government cannot change its portfolio mix sufficiently to obtain the most efficient risk-return trade-off. 32 By recognising that the Government has assets within its portfolio that are non-marketable, the assessment of investment risk has been changed for the Government. Non-marketable assets within a portfolio is now a function of the covariance of an asset with the total stock of non-marketable assets, as well as with the total stock of marketable assets. The weight this additional term receives in determining risk depends on the total size of non-marketable assets relative to marketable assets. The investment risk associated with any asset that is positively correlated with the total of non-marketable assets will be higher than the risk implied by the simple form of the CAPM. It seems reasonable to Page 18 of 27 rate derived in assessing privatisation options. Without the inclusion of an adjustment for non-marketable assets, the discount rate may be understated. Thus, with a non-optimal portfolio, by the inclusion of non-marketable assets, Government investment risk will be assessed to be greater for an asset that is Government owned than an equivalent asset owned in the private sector. 4.2 GOVERNMENT REGULATION Government regulation can be defined as systematic investment risk. Therefore, all assets, both Government and private sector owned, are influenced by Government regulation risk factors that cannot be eliminated through diversification. However, the sensitivity of each sector to these Government regulation risk factors will vary. Sensitivity of an asset to these Government regulation risk factors will depend on two conditions; the type of Government regulation and the assets exposure to this Government regulation33. Thus, equivalent assets with similar existing risk profiles will be affected by different amounts of risk due to the assets sensitivity to each condition associated with Government regulation risk. For example, a firm operating in the clothing industry in the United States will have different sensitivities to Government regulation risk factors than a firm operating in the clothing industry in Australia34. You would expect that if Government regulation were different within Australia then firms operating in different Australian states would also have different sensitivities to government regulation risk. Based on the above argument two private sector firms operating under the same conditions would have similar sensitivities to Government regulation risk. However, assume that the return on the total non-marketable assets is positively correlated with the return on the market. This would suggest that the market return-risk trade-off is lower than that suggested, by the simple form of the CAPM model. 33 Just as Roll (1977) and Ross and Roll (1984) identify systematic risk factors affecting firms differently due to their existing risk profiles, it can be stated that if Government regulation is a systematic risk factor it will also affect each firm differently. This affect, as shown by Cochrane and Hansen (1992) can be positive, negative or risk neutral to the existing risk profile. 34 As the firms would be operating under different legislation and laws that governs their activities. Page 19 of 27 if one firm were owned by Government their sensitivities to Government regulation risk would be different. If the Government acted in a purely commercial manner and influenced the firm as a shareholder with its primary objective as a wealth maximiser, then Government ownership would not have any significant difference in the determination of Government investment risk than for a similar firm operating in the private sector. However, history demonstrates that Government ownership influences the way the firm operates and the way Government regulation is made35. One argument suggests that the sensitivities to Government regulation risk factors for a Government owned firm will be less than a firm privately owned (with similar riskreturn profile)36. One reason suggested for this is that the Government will not make regulation that would disadvantage the firm’s profitability. This view puts forward that Government, and in particular politicians, are wealth maximisers first and foremost. However, realistically, this is unlikely to be for a number of reasons. Firstly, politicians may not be wealth maximisers. They must take into account welfare matters which include externalities, such as the environment, minority lobby groups, labour issues and so on. All of these potentially have a negative effect on profit. In addition, Government firms are traditionally slower to adapt to negative regulation than the private sector. As an example, consider the case of two identical firms supplying clothing to the public and Government regulation is introduced to reduce import tariffs. The private firm realising that future profits will be reduced may focus its resources towards other areas. However, the Government owned company may not, or be allowed to, direct its resources towards other more profitable areas as it would potentially cause job losses and may indirectly support political opponents. Therefore, in the long term the Government owned firm would lose financially. Thus, Government regulation risk is potentially greater when a firm is Government owned. While Government owned firms may be wealth maximisers, greater Government regulation risk prevents it from operating as efficiently. As the Government firm has a 35 36 Boardman, A.E. and Vining, A. R., (1989). Cochrane, J. H. and Hansen, L. P. (1992). Page 20 of 27 greater sensitivity to Government regulation risk is would necessitate the assessment of a higher discount rate. This would provide a strong argument for privatisation. 5.0 MEASUREMENT OF GOVERNMENT INVESTMENT RISK Investment risk has been extremely difficult to measure and to incorporate into any analysis. Although the concept of investment risk is universally recognised, the appropriate measure of risk remains controversial. Before the 1960’s risk measurement was an imprecise science often based on the instincts and judgement of the individual attempting to calculate risk. As such, the use of any risk models remained hotly debated. However, in the 1960’s a new group of valuation models were conceived to assist in asset pricing. The first of these models, the modern portfolio theory (MPT) evolved gradually. Modifications and additions were made to this model to become the most widely known metamorphosis called the Capital Asset Pricing Model (CAPM)37. Since its development in the 1960’s businesses have increasingly used the CAPM to assist in their investment decision-making processes. The CAPM provides a riskadjusted expected rate of return. That rate can be used to discount projected future cash flows in order to value a project, division or business, or indeed any business related activity. The CAPM postulates that a single type of risk, known as market risk, effects expected asset returns. The CAPM measures risk objectively and defines risk explicitly as the volatility of an asset’s returns relative to the volatility of the market portfolio’s returns. Thus, investment risk can be defined under CAPM as a measured relationship between that of an asset and the market. However, the problem of using the CAPM approach with Government assets is that, in most cases, Government assets have never existed in the commercial world, in other words, these assets do not operate in CAPM ‘market’. Therefore, Government 37 Harrington, D. R. (1987). Page 21 of 27 owned assets have no market relationship which is necessary to measure investment risk. A CAPM model approach could be used by developing accounting determined risk measures or using the pure-play approach38. However, these methods, as with the CAPM model, would not recognise any differences in investment risk for an asset if it is Government or Private sector owned. This is because CAPM only recognises one source of risk, that is, market risk. Thus, using the CAPM approach, it does not matter if assets are owned by the Government or private sector. Clearly the CAPM approach is insufficient to test any hypothesised differences between Government and private sector investment risk. As many Government owned assets are non-commercial and/or operate outside the scope of the CAPM defined market, it is logical to assume it is possible that some investment risks faced by Government in their investment decisions may be nonmarket or extra-market risks. In recognising that additional non-market or extra-market risks may exist, the use of a multi-factor CAPM should be considered as a viable option39. The advantage of the multi-factor CAPM is that it will allow for the inclusion of hypothesised extra-market or non-market risk factors. The inclusion of these factors in a model will provide the user with three possible outcomes. Firstly, Government risk associated with investment decisions is the same as for the private sector. Secondly, investment risk is lower for the Government than it is for the private sector, or the third possible alternative discussed in Section 4, that the risk associated with Government investment decisions is higher than that assessed for the private sector. All three possible alternative possibilities, as previously discussed, will have a significant influence on the privatisation process. The arbitrage pricing theory (APT), first presented by Ross (1976) recognises that several different broad risk factors combine to influence asset returns. Likewise, 38 For a comprehensive discussion on accounting measures of risk see Beaver et. al. (1970), and for the pure-play approach see Kaplan, P. D. and Peterson, J. D. (1998). Page 22 of 27 factor models that developed from APT evaluate the impact of a series of broad factors on the performances of various assets. A reliable factor model provides a valuable tool to assist with the identification of pervasive factors. According to a factor model, the return-generating process for an asset is driven by the presence of the various common factors and the assets unique sensitivities to each factor. Again, the development of a multi-factor model would appear to be another appropriate tool in the understanding of Government investment risk and its impact on the privatisation process40. 6.0 CONCLUSION The identification and measurement of investment risks has always been difficult. To this day the issues surrounding investment risk are a matter of considerable debate. Likewise, the identification and measurement of investment risk associated with Government investment decisions are no exception to this. Government investment risk analysis has attracted critical attention over the last two decades with the increase in Privatisations worldwide. Debate in this area provides for three alternative positions, that is, Government investment risk can either be higher, lower, or the same as private sector investment risk. The accurate measurement of Government investment risk has a profound impact on privatisation decision making. It is suggested that using either multi-factor CAPM or multi-factor models via analysing and pricing individual investment risk factors could provide a more accurate measurement of investment risk Therefore, using multi-factor CAPM or multi-factor models appear to be the most appropriate direction for future research to develop. 39 40 Using a multi-factor CAPM also requires the use of marketplace proxies such as the pure-play or accounting measures or risk. The difficulty in the use of multi-factor models for this purpose is that the investment risk factors identified must be significant. Page 23 of 27 BIBLIOGRAPHY 1) Arrow, K. (1965), “Criteria for Social Investment”, Water Resources Research, No. 1, pp. 1 – 8. 2) Arrow, K. (1966), “Discounting and Public Investment Criteria”, in A. V. Kneese and S. C. Smith (eds), Water Research, Baltimore, MD, John Hopkins University Press. 3) Arrow, K. and Lind, R. (1970), “Uncertainty and the Evaluation of Public Investment Decisions” American Economic Review 60(2), 364-78. 4) Bailey, M. and Jensen, M. (1972), “Risk and the discount rate for public investment”, in M. Jensen (ed.), Studies in the Theory of Capital Markets, Praeger, New York. 5) Beaver, W., Kettler, P. and Scholes, M., (Oct 1970), “The Association Between Market Determined and Accounting Determined Risk Measures”, The Accounting Review, pp.654 – 682. 6) Boardman, A.E. and Vining, A. R., (Apr 1989), “Ownership and Performance in Competitive Environments: A Comparison of the Performance of Private, Mixed and State-Owned Enterprises”, Journal of Law and Economics, Vol. 32, pp. 1 – 33. 7) Brealey, R. A. and Cooper, I. A. and Habib, M. A. (1997), “Investment Appraisal in the Public Sector”, Oxford Review of Economic Policy 13(4), 17-28. 8) Cochrane, J. H. and Hansen, L. P. (1992), “Asset Pricing Explorations for Macroeconomics”, NBER Working Paper 4088. Page 24 of 27 9) Conner, G., (1984), “A Unified Beta Pricing Theory,” Journal of Economic Theory, 34, pp. 13 – 31. 10) Constantinides, G. M. and Donaldson, J. B. and Mehra, R. (1998),” Junior Can’t Borrow: A New Perspective on the Equity Premium Puzzle”, NBER Working Paper 6617. 11) Eckel, C. C. and Vermailen, T., (1986), “Internal Regulation: The Effect of Government Ownership on the Value of the Firm”, The Journal of Law and Economics, 29, pp. 382 – 403. 12) Elton, E. J, and. Gruber M. J., (1995), Modern Portfolio Theory and Investment Analysis, Fifth Edition, , John Wiley & Sons Inc. 13) Evans, M. D. (1986), “Public Investment – What is a Fair Return?”, Discipline of Accounting and Finance, The Flinders University of South Australia, Research Paper 6/86. 14) Grant, S. and Quiggin, J. (1999), “Public Investment and the Risk Premium for Equity”, Australian National University Working Paper No. 360. 15) Harrington, D. R., (1987), “Modern Portfolio Theory, The Capital Asset Pricing Model, and Arbitrage Pricing Theory: A User’s Guide”, Second Edition, PrenticeHall. 16) Kaplan, P. and Peterson, J. D., (1998), “Full-Information Industry Betas”, Financial Management, Vol. 27, No. 2, Summer, pp. 85 – 93. 17) Klein, M. (1997), “The Risk Premium for Evaluating Public Projects”, Oxford Review of Economic Policy 13(4), 29-42. 18) Kockerlakota, N, (1996), “The Equity Premium: It’s Still a Puzzle”, Journal of Economic Literature 34(1), 42-71. Page 25 of 27 19) Lawriwsky, M. and Kiefel, C., (1993), in Davis, K. and Harper, I (eds.), “Privatisation: The Financial Implications”, Allen and Unwin, pp 34 – 56. 20) Lintner, J., (February, 1965a),”The Valuation of Risk Assets and the Selection of Risky Investments in Stock Portfolios and Capital Budgets,” Review of Economics and Statistics, XLVII, pp. 13-37. 21) Mankiw, N. G. (1986), “The Equity Premium and the Concentration of Aggregate Shocks”, Journal of Financial Economics 17, 211-19. 22) Mehra, R. and Prescott, E. C. (1985), “The Equity Premium: a Puzzle”, Journal of Monetary Economics 15(2), 145-61. 23) Moore, J., (1992), “British Privatisation – Taking Capitalism to the People”, Harvard Business Review, January/February, pp. 115 – 124. 24) Mossin, J., (October, 1996)“Equilibrium in a Capital Assets Market,” Econometrica XXXIV, pp. 768-83. 25) Munckon, P., (April 2000), “More Sell-offs to Come.” Shares Magazine,, pp. 60 – 64. 26) Officer, R. R. and Quiggin, J. (1999), “Privatisation: Efficiency or Fallacy? Two Perspectives”, Committee for Economic Development of Australia (CEDA) Information Paper No. 61. 27) Pigou, A. C. (1920). “Economics of Welfare”, 4th edn, Macmillan, pp. 24 – 30. 28) Roll, R., (May 1977), “A Critique of the Asset Pricing Theory’s Tests,” Journal of Financial Economics, 4, pp. 129 – 176. 29) Roll, R. and Ross, S. A., (June 1984), “ A Critical Reexamination of the Empirical Evidence on the Arbitrage Pricing Theory: A Reply, “ The Journal of Finance, 39, No. 2, pp. 347 – 350. Page 26 of 27 30) Ross, S. A,. (1976), “The Arbitrage Theory of Capital Asset Pricing,” Journal of Economic Theory, 13, pp. 321 – 360. 31) Samuelson, P. A. (1964), “Principles of Efficiency: Discussion”, American Economic Review, No. 54, pp. 93 – 96. 32) Sharpe, W. F., (September 1964), “Capital Asset Prices: A Theory of market Equilibrium Under Conditions of Risk”, Journal of Finance, XIX, pp. 425 – 442. 33) Waterman, E, (1993), in Davis, K. and Harper, I (eds.), “Privatisation: The Financial Implications”, Allen and Unwin, pp 23 – 33. 34) Vickers, J. and Yarrow, G., (1988a), “Privatisation: An Economic Analysis”, MIT Press. 35) Vickrey, W., (May 1964), “Principles of Efficiency: Discussion,” American Economic Review, LIV, pp. 88 – 92. 36) Yarrow, G., (1986), “Privatisation in Theory and Practice”, Economic Policy, 2, pp. 324 – 364. Page 27 of 27