Stikeman Elliott 1 Canada amends its thin cap rules By: Elinore J

advertisement

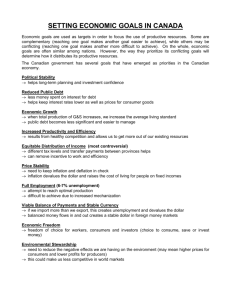

Canada amends its thin cap rules By: Elinore J. Richardson Introduction The treatment for tax purposes of interest paid by a resident to a non-resident is one element of a more general concern which appears to be occupying more than one tax administration currently: - the sharing of tax revenues from cross-border investment activities by taxpayers between "source" and "residence" jurisdictions. The merits of source and residence based taxation have long been debated by tax administrations and economists alike. In Canada, legislators have attempted to marry the conflicting demands of varying concepts of tax neutrality for Canadian business with those of revenue protection, crucial to economic growth and job creation. Thin Capitalization – the Rationale Economists tend to distinguish between international investors that are foreign portfolio investors (non-control) and those that are involved in foreign direct investment (control). As foreign portfolio investors are at arm's length with issuers, the presumption is that debt obligations they acquire reflect the true substance of the arrangements between them and their borrowers. Foreign direct investors, however, are often parent multinationals, their goals being the exploitation of international business opportunities and the efficient allocation of consolidated revenue and expense among various jurisdictions. Given these objectives, intra-firm debt transactions can, inter alia, be used to manipulate group expenses to maximise after-tax return. In such circumstances, a capital importing country can find that the funding of a group subsidiary, resident in its jurisdiction, with interest bearing debt will result in an erosion of its tax revenues. Most jurisdictions, therefore, have some form of transfer pricing rules designed to ensure that the return on such debt is reasonable and bears a similarity to some arm's length standard. The more difficult issue has been the way in which jurisdictions determine what portion of intra-firm debt is disguised equity. Thin capitalization rules are one means of addressing this issue. As early as 1966, the Canadian Royal Commission on Taxation recognized that differences in the tax treatment of interest and dividends under the Canadian tax system created an obvious incentive for a non-resident to capitalize a Canadian subsidiary with debt rather than equity. The problem was acknowledged by the Canadian government in its 1969 white paper entitled "Proposals for Tax Reform": STIKEMAN ELLIOTT 2 "under present law it is attractive for non-residents who control corporations in Canada to place a disproportionate amount of their investment in the form of debt rather than shares. The interest payments on this debt have the effect of reducing business income otherwise taxed at 50% and attracting only the lower rate of withholding tax on interest paid abroad." Shortly thereafter, in 1972, Canada became one of the first countries to introduce statutory "thin capitalization rules". These rules, with some minor tinkering, have remained essentially unchanged for almost three decades. The Current Canadian Rules Canada's current rules are contained in subsection 18(4) to 18(8) of the Canadian federal Income Tax Act1. Essentially, those rules disallow the deduction of interest, otherwise deductible, that is paid by a corporation resident in Canada to a specified non-resident, to the extent that the ratio of "outstanding debts to specified non-residents" to equity exceeds 3:1. Unlike the rules introduced, for example, in 1987 by Australia, Canada's rules, to date, have applied only to the debt of corporations resident in Canada. It has, therefore, not been unusual to see planning involving partnerships, trusts or branches of foreign corporations which are outside the application of the Canadian rules. Specified Shareholder For purposes of these rules, the Act defines a "specified non-resident shareholder" to be a "specified shareholder" who, at that time, was a non-resident. A "specified shareholder" is defined to be a person who either alone or together with persons with whom that person is not dealing at arm's length, owns shares of the capital stock of a corporation that: (a) give the holders the right to cast 25% of the votes at an annual meeting of the shareholders or, (b) have a fair market value of 25% or more of the fair market value of all of the issued and outstanding shares of the corporation. The Act also includes certain anti-avoidance rules which will attribute or re-distribute ownership among persons with various rights or to an issuing corporation in specified circumstances. Debts "Outstanding debts to specified non-residents" of a corporation at any particular time in a taxation year, means the total of all amounts, each of which is an obligation to pay an amount to a specified non-resident shareholder of the corporation or to a non-resident person who was not dealing at arm's length with a specified shareholder (the "specified non-resident"). Any loan made by a specified non-resident (the "first lender") to another person, on condition that a loan (the "back to back loan") be made to the corporation, will be deemed (to the extent of the amount of the lesser loan) to be made by the first lender to the corporation. RSC 1985, c. 1 (5th Supplement), as amended, hereinafter referred to as the "Act." Unless otherwise stated, statutory references in this article are to the Act. 1 STIKEMAN ELLIOTT 3 Debts or obligations included for this purpose are loans and other similar indebtedness, such as trade payables. Late payment charges on the purchase of goods and services from related nonresidents will also be included. Not included is non-interest bearing debt. Also, not included currently, are deposit or guarantee arrangements entered into by a foreign parent or related corporation in support of a borrowing by a resident Canadian corporation: see Examples A and B. Example A Foreign Bank Foreign Co. Deposit Foreign Bank Affiliate Loan Canadian Co. Example B guarantee Foreign Co. Foreign Bank loan Canadian Co. STIKEMAN ELLIOTT 4 It is to be noted that, under the current rules, Canadian Co. should be entitled to contract unlimited borrowings from the foreign lenders. Assuming interest paid on the loans otherwise, meets the tests of deductibility, subsection 18(4) of the Act should pose no limitations. Moreover, the interest paid by Canadian Co. would, most likely, be exempt from Canadian non-resident withholding tax. Where the specified non-resident is itself a bank, which is considered to be an "authorized foreign bank" as defined in the Act, debt outstanding from a resident Canadian corporation will be excluded from debt outstanding for purposes of the thin capitalization rules, by reason of a proposal contained in the February 1999 federal budget, so long as interest payments on that debt are included in the foreign bank's income that is subject to income tax in Canada. Equity For purposes of determining whether the ratio has been met, a corporation resident in Canada must compare the greatest aggregate amount that the corporation's outstanding debts to specified non-residents were, at any time during the year, to equity. Equity for this purpose means: the retained earnings of the corporation at the commencement of the year on an unconsolidated basis determined in accordance with generally accepted accounting principles, subject to certain exceptions, among them those relating to recent characterizations of equity or debt for financial reporting purposes, the corporation's contributed surplus at the commencement of the year, to the extent that it was contributed by specified non-resident shareholders, and the greater of the corporation's paid-up capital at the beginning or the end of the year in respect of shares held by specified non-resident shareholders. Tiering The current rules have three twists, two of which have not been affected by the proposed changes. First, subsection 18(4) does not recharacterize interest on debt which exceeds the limits prescribed by the rules as dividends. It simply denies a deduction by the corporation paying it. The effect of the denial is, economically, to treat the amount of excessive interest as a dividend in that it is subject to Canadian income tax at the corporate level. However, for all tax purposes, i.e. for Canadian non-resident withholding tax purposes, it remains interest. That means that Canada will charge its domestic non-resident withholding rate of 25%, reduced, as applicable, by relevant treaties. Interest will normally be taxed at a treaty rate of 10%, while dividends will be taxed at either a general rate of 15% or at 5%, in the case of a foreign corporate recipient with a substantial interest. Second, the Canadian thin capitalization rules are, for the most part, straight forward and relatively easy to apply. Situations do arise, however, due to the fact that the rules do not look to STIKEMAN ELLIOTT 5 "ultimate ownership" but only to "direct ownership", which can give rise to costly oversights. The following example illustrates the type of situation which can arise. Example C Foreign Co. 100% equity 100% equity Canadian Co. Foreign Co. A Loan 100% equity Canadian Opco. In this example, Canadian Opco. requires funds. Foreign Co. A is Foreign Co.'s. financing subsidiary. It lends the money. The thin capitalization rules will apply to disqualify all interest payable by Canadian Opco. as it will have no paid-up capital or contributed surplus from specified non-resident shareholders, unless its retained earnings alone are sufficient to provide the coverage. Finally, the elements of the formula may give rise, in certain cases, to anomalous results where a Canadian corporation is involved in the acquisition of a target corporation or another transaction which requires that for a short period it increases substantially its intra-firm debt. Assume, for example, that Foreign Co. creates Canco A and Canco A acquires Canco B. Assume further that Canco A is capitalized with a significant amount of debt from Foreign Co. to make the acquisition. That debt is almost immediately repaid. In measuring debt to equity, Canco A must, for its first taxation year, match the highest debt at any time in the year against the greater of its paid-up capital from Foreign Co. at the commencement of the year (a nominal amount on incorporation prior to making the bid) and that at the end of the year (the amount after repayment of the debt). A portion of Canco A's interest will be non deductible. Had Canco A's shareholders realized the situation, they could have put Canco A back on side with an additional subscription of capital immediately before STIKEMAN ELLIOTT 6 the year end under the current rules. This may no longer be possible under the budget proposals described below. The Technical Committee on Business Taxation The Technical Committee on Business Taxation, established by the Minister of Finance for Canada in March 1996, to recommend ways to improve the business tax system, issued its report (the "Mintz Report") in December 1997. The Mintz Report, inter alia, reviewed the federal-provincial general corporate rates of tax in Canada, noted the increasing role of Canada as a capital exporter and highlighted, in the area of international taxation, the need for a series of changes to reduce erosion of the Canadian tax base. Among the reasons for this, the Mintz Report cited Canadian corporate tax rates which the Committee described as "internationally non-competitive", discouraging the location of business operations in Canada and resulting, as well, in an erosion of the Canadian tax base. The Mintz Report noted that the Canadian economy "is increasingly integrated with the global economy". Canada, historically a capital importer, exports almost as much capital as it imports, the Mintz Report acknowledged. "Foreign direct investment into Canada totaled approximately $170 billion in 1995" compared with outbound foreign direct investment of approximately $140 billion in the same year. As relatively little domestic tax revenue is traditionally raised by tax administrations from outbound foreign direct investment, the change in Canada's role was considered as perhaps necessitating a re-evaluation of past policies. The Mintz Report also commented on the thin capitalization rules as follows: "In general, the Committee is of the view that the thin capitalization rules are working well, and are not a major impediment with respect to the day-to-day operations of Canadian businesses. The rules are simple and effective, and the paucity of jurisprudence with respect to the rules suggests that disputes with the Canadian revenue authorities have been rare…" Nonetheless, the members of the Committee could not resist the temptation to tinker. The Mintz Report contained the following recommendations: "the existing ratio of 3 to 1 should be reduced to 2 to 1, as a closer proxy for financing that would generally be available in an arm's length context." "the rules should be extended in their application to Canadian branches of foreign corporations, and to partnerships and trusts." STIKEMAN ELLIOTT 7 "the provisions on back to back loans should be extended to all indebtedness (including funds on deposit)." On balance, the Mintz Report recommended that "guaranteed debt not be included in the thin capitalization provisions at this time" as it "might […] disrupt normal commercial financing arrangements". The Budget Proposals In the government's first federal budget of the millenium, the Minister of Finance has flirted with a few of the Business Taxation Committee's proposals in the international area but has refused to dance. Hard issues have been left for later. Nonetheless, the government has decided to embark on a reform of the thin capitalization rules which will impact foreign direct investment in Canada. The government initially indicated in the budget proposals that it would reduce the threshold ratio of debt to equity from 3:1 to 2:1, alter the manner in which the ratio was to be calculated, extend the definition of debts outstanding to debt owing to a third party that is guaranteed or secured by a specified non-resident, and repeal a current exemption from the rules applicable to developers and manufacturers of aircraft and aircraft components. These amendments were proposed to take effect for taxation years that begin after 2000. In addition, the government indicated that it intends to initiate consultations to extend the application of the thin capitalization rules to other arrangements and business structures. Specifically mentioned were partnerships with non-resident members, trusts with non-resident beneficiaries and Canadian branches of non-resident companies carrying on business in Canada. Also noted were debt substitutes, such as certain types of leases. Threshold Debt-Equity Ratio The reduction of the threshold ratio from 3:1 to 2:1 was warranted, said the government in the Supplementary Information which accompanied the budget, as it provides a "better measurement of excessive reliance on related-party debt financing in the context of actual Canadian industry debt equity ratios". No separate consideration was given to appropriate debt equity ratios for financial institutions, although it is understood that some accommodation may be under review. No economic data was supplied by the government in support of its assertions. STIKEMAN ELLIOTT 8 If one accepts that a fixed debt to equity ratio standard, though inflexible and arbitrary, is preferable to a multi-factor arm's length standard such as that advanced by the OECD, in the interest of increased certainty and reduced administration and compliance costs, the only question which then remains is how stringent tax policy makers wish to be with respect to intra-firm debt. Increasingly, other jurisdictions have introduced lower thresholds, or reduced those, previously at 3:1. The US "earnings stripping rule", introduced in 1989, adopts a safe harbour of 1.5 to 1.0 but disqualified interest (non-deductible to the extent a US group has excess interest expense) may be carried forward indefinitely. Australia recently expanded the debt base to which its thin capitalization rules apply, but reintroduced the three to one standard after having lowered it for a short period to 2:1. A 2:1 single factor standard, if adopted by Canada, will certainly do nothing to encourage foreign investors to increase investment activity in Canada. Calculation of Equity on an Averaged Basis The change proposed will require that a Canadian corporation with debt outstanding to specified non-residents compute retained earnings at the beginning of the year and compute contributed surplus and paid-up capital attributable to specified non-residents at the beginning of each month in a year. The corporation will then measure the amount it has calculated against the greatest total amount of debt owing to non-residents at any time in each month of the year and determine the average annual ratio of debt to equity. The proposal is justified by the government in that it will "give less weight than the current rules to debt levels that are temporarily high". While this may be true, it is also true that it will make it more difficult to rectify oversights which occur during the course of a year. It will also clearly put an end to any planning based on artificial inflation of paid-up capital over a corporation's year end. If, as the government suggests, the modification is to deal with temporarily high levels of debt which can have a disproportionate effect, perhaps, at the very least, given the increased administrative cost to taxpayers of instituting yet another information gathering system and of maintaining adequate records to support the calculations, the legislation might be drafted to permit taxpayers to decide annually whether or not to use the monthly calculation. As another option, a weighted calculation of debt only could have been proposed. Broadening of the Conditional Loan Rule The expressed intention is to extend the ambit of the rules by including, as debt outstanding, loans to a Canadian corporation from a third party that are guaranteed or secured by a specified nonresident. It is understood that, while the budget resolution is not qualified, the government may be STIKEMAN ELLIOTT 9 giving some consideration, at the least, to "appropriate" carve outs. This review process may result in a deferral of the application of the rules. If one accepts, as apparently the Australian legislators do, the impossibility of determining what constitutes "good" and "bad" debt for this purpose, the solution, one must conclude, must be either to include all debt with a consequent increase in the ratio or to establish bright-line tests which can be applied with certainty. It will be interesting to see what the government comes up with faced with a Canadian business community constituted in large part of a number of strong and profitable Canadian subsidiaries of US and other foreign multinationals, very few of which would, in all probability, be rated, all of whom keep competitive information extremely private and most of whom have been permitted to do so over long time periods by using parent or group results as the basis for external borrowing! In such an environment, how will it be possible to design a bright-line test which will separate tax-motivated transactions. From those entered into primarily for commercial purposes? Moreover, what possible advantage can Canada think to obtain by forcing Canadian borrowers across the board into financial arrangements which have as their end to increase the cost of borrowing! Similar to the case of guarantees is that of security. While there have clearly been situations where corporations related to Canadian borrowers have put funds on deposit with a foreign bank to "facilitate" borrowings by a Canadian corporation, how will corporate groups, under the new proposals, deal with lenders who will seek the greatest amount of security possible even if it is not an absolute requirement of a transaction? Repeal of Aircraft Developers and Manufacturers Exemption There is nothing really which can be said. The government seemingly made no comment when the exemption was introduced and has been similarly silent in face of its demise. Non-Corporate Borrowers It remains to be seen what will come of the government's request for comment and its review. Australia has tackled the problem and it is to be expected that the Australian legislation will be the subject of review. While it is clear that the application of the thin capitalization rules only to corporate entities does leave the opportunity for base erosion, the offensiveness of that erosion will have to be weighed carefully against the legislative complexity which will result from any attempt to reduce it. Grand Fathering The government's proposals are intended to have application to taxation years beginning after 2000. So long as the proposed rules will have application only to intra-firm debt the lead time of almost a year in most cases to put ratios on side, should be sufficient. However, if the government STIKEMAN ELLIOTT 10 intends to proceed with the more far reaching changes affecting guaranteed debt, the period seems hardly enough. Many international borrowings by Canadian issuers have no call provisions during a specified period; others have call provisions but exercisable only at a significant economic cost to the borrower. It is to be hoped that the legislators will take these concerns, as well, into consideration as they review the proposals. Conclusion It is clear that a number of factors have conspired to encourage foreign multinationals to increase the debt of their Canadian subsidiaries over the past several years. Many of these factors have been within the control of the Canadian government. The first and most significant has been Canada's insistence on maintaining a considerably higher federal-provincial general corporate rate of tax in face of reductions by several of its major treaty partners. Also, important has been Canada's generous rules, which permit deduction of interest expense on borrowings to finance foreign investment. Third, tax changes in foreign jurisdictions, notably the US, which have restricted deduction domestically of interest costs relating to foreign investment, have also encouraged shifting of such costs to other jurisdictions. It is also clear that "shifting", or more exactly, "doubling" has been facilitated since the introduction by the US of its "check-the-box" regulations in 1996 and, also, by differing jurisdictional interpretations as to the character of debt and equity. The result has been that certain multinationals have been able to structure their affairs so as to obtain additional deductions of interest in one or two foreign jurisdictions, without ever giving up their interest deduction domestically. Add to these considerations that Canada's role has been slowly changing over the last decade and a half from that of a country dependent on foreign capital to that of one which has made significant strides toward becoming a substantial exporter of capital. Moreover, many of Canada's important treaty partners have been reviewing and refining their positions as the jockeying internationally for tax revenues continues. Amidst these developments which have raised serious concerns from Canada's perspective as to where its tax revenues will come from in the future, though one might well take issue with an approach which might have benefited from a more comprehensive review and considered action, it is not difficult to see from whence the tax man cometh!