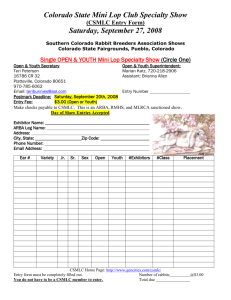

Rebecca Brofft

advertisement

Water Conflict Running Head: WATER CONFLICT ON THE FRONT RANGE Boom or Bust on the Front Range: Conflict over Colorado’s Limited Water Resources Rebecca Brofft Colorado State University 1 Water Conflict Abstract Entrenched in long legal battles and animosity, the complex struggle for water rights in Colorado reveals the opposing needs and values of many stakeholder groups. From agriculture to recreation, many of Colorado’s industries are mutually dependent, but these parties have rarely cooperated to resolve water issues in the past. Traditional approaches to conflict management are no longer appropriate or acceptable for water rights issues. A transformative approach is needed. In this paper, I argue that participatory modeling of water conflicts would improve these stakeholder relationships, build mutual respect and understanding, and promote creative problem solving for the future. 2 Water Conflict 3 Water is a vital resource in Colorado’s arid environment, and the conflict over limited water resources is central to the history and politics of the Western landscape. Writer Rick Bass notes that, “water is the second-most important element critical to minute-by-minute survival, much less to the endurance of civilizations and the expansion of culture” (Bass, 2007, p. IX). Many of Colorado’s economic activities depend on water supplies: agriculture, resource extraction, hydroelectric energy production, residential development, tourism and recreation. Increasing development pressures, the unpredictability of drought, climate change concerns, and demographic shifts intensify this historically entrenched battle for water rights. Constrained by natural forces and resource availability, water conflict is a complex social problem that necessitates creative and non-traditional management approaches. In order to transform the polarized struggles of Colorado’s Front Range water conflict into productive partnerships, the situation requires improved communication between all the current stakeholders. The diverse perspectives of each stakeholder are necessary in analyzing the historical basis, current context, and opportunities for progress in Colorado’s modern water conflicts. Participatory modeling, a collaborative learning process, would be an effective approach to the transformation of the current conflict. By assembling stakeholders to work toward a shared understanding of water rights issues, the participants can create a vision for the future that promotes collaborative problem solving and overcomes the traditional barriers to conflict resolution. History of Conflict The story of disputes over Colorado’s limited water resources began with the decisions and rules established over 150 years ago. The Colorado Doctrine of the 1860s defines water as a public resource to be used for the benefit of public agencies and private individuals (Hobbs, 2004). This framework defines a water right as the entitlement to a portion of this public Water Conflict 4 resource. The doctrine additionally permits landowners to cross other private lands to extract, divert, or transport water for their own benefit. As Colorado’s land became increasingly populated and developed in the late 19th century, the Doctrine of Prior Appropriation (1876) further clarified those rights, restrictions, and stipulations by establishing a priority system for water use. Commonly known as “first in time, first in right,” this granted senior water rights to earlier water users, and junior rights for subsequent water needs (Hobbs, 2004, p. 6). The second principle of the doctrine requires that all diverted water must be put to beneficial use; in other words, the owners of water rights are expected to either “use it, or lose it” (Hobbs, 2004, p.8). The precedent of beneficial use established over 100 years ago has been a constant source of water conflict in the state. Conflict between agricultural and residential needs for limited water supplies quickly became apparent. The Colorado Constitution provides domestic preference to water supplies, allowing residential water users access to water resources prior to agricultural and manufacturing needs in times of shortage (Hobbs, 2004). Residents gain access to these water rights either through priority or the power of condemnation by the government. Water transported from the Western Slope to the eastern Front Range through the Colorado Big Thompson Project has become an additional point of contention. The water from this project is considered foreign water, and thus is not subject to the priority system (Hobbs, 2004). Rights for this water can be purchased and sold for agricultural or municipal use only, which puts these two uses in direct competition. Over time, the Doctrine of Prior Appropriation has changed to accommodate shifting water demands and social values. In 1973 Colorado developed the Instream Flow Program, granting the Colorado Water Conservation Board the ability to acquire water rights to “preserve the natural environment to a reasonable degree”(Hobbs, 2004, p. 7). Under this program, Water Conflict 5 instream flows are considered a beneficial use of the resource, placing value on environmental protection. Subsequently, Colorado water law added provisions to protect water for recreational use. In 2001, beneficial use was redefined to include recreational diversions to provide quality boating, kayaking and fishing experiences (Hobbs, 2004). By the turn of the 20th century, the most desirable water rights had been claimed, especially on the Front Range (G. Wallace, Personal Communication, October 13, 2008). Currently, there are no new Colorado water rights available for distribution. This pressures the existing water supplies, increases the value of water as a precious resource, and maintains a high demand for water rights. Context of Conflict Water is a scarce resource, and its distribution is determined by precipitation and climate. Water is most accessible in the late spring and early summer, based on runoff from snowpack in the Rocky Mountains. However, climatic patterns shift throughout the year and over time, so rain and snow fall unevenly on the state. Almost 90 percent of Colorado’s precipitation, for instance, falls on the Western Slope, with the remaining 10 percent falling on the Front Range and the Eastern Plains (Jordan, 2003). Use of water also varies spatially within Colorado. While the Western Slope may receive the most precipitation, 65 percent of Colorado’s residents are found on the Front Range—on the opposite side of the Rocky Mountains. In addition, agricultural needs account for 90 percent of diverted water use in Colorado, but most agricultural land is located in the eastern half of the state, where water is in short supply (Jordan, 2003). Precipitation in the Rocky Mountains is the primary water source for Colorado. No rivers flow into Colorado, making it the only state that entirely supplies its own water. Colorado is obligated, through interstate agreements or compacts, to satisfy water needs outside the state, Water Conflict 6 which places additional pressures on an already limited water supply. Colorado currently holds compacts with Arizona, California, Nevada, New Mexico, Utah, Wyoming, and Kansas. Natural forces limit water supply, and the location of human activities determines water needs, but legal water rights constrain the availability of water for use. Water rights entitle the owner to the same amount and quality of water each year. Because the priority system guarantees water to senior rights before others, in times of shortage or drought not all water rights are satisfied during the year. In the words of the Colorado Climate Center’s head climatologist Nolan Doesken: “Climate determines where the water is and when the precipitation falls, but water rights determine who gets the water and where” (N. Doesken, personal communication, September 10, 2008). Water Rights Conflict Map Natural resource conflicts are often complex, multi-faceted, and overwhelming for the parties involved. Water conflicts in Colorado are entrenched in history, policy, litigation, and polarization. In order to properly understand and analyze a conflict of this scope, a graphic model can effectively communicate the complexities of the problem and the relationships of the parties involved. A conflict map is a graphic model that visually represents the interactions of the relevant stakeholders in a conflict (Fisher, et al., 2000). Conflict mapping can provide a broad view of the relationships that influence the dynamics and challenges of Colorado water appropriation and use. While the map simplifies the situation to represent only the interactions between the main conflict parties, it is still important to consider the underlying needs, values and rights that characterize water disputes in Colorado. The various groups and parties involved in Colorado water conflict are introduced below, with careful consideration to the needs and motivations of each party. The particular tensions that typify water conflict are also described. The conflict map in Figure 1 visually displays the Water Conflict Figure 1. Water Conflict on the Front Range. 7 Water Conflict 8 relationships between each of these stakeholders, as well as the location of tensions between parties. Stakeholders Agriculture Agricultural interests in Colorado water conflicts primarily consist of farmers on irrigated land. The agricultural industry contributes over $4 billion to Colorado’s economy, and is both historically and currently a primary land use in the state. Agriculture uses nearly 90 percent of the 12.4 million acre-feet of water diverted annually in Colorado, but much of that water is returned to the watershed for downstream uses (Jordan, 2003). According to a recent article in the Fort Collins Coloradoan, water is the most valuable crop, or resource, that farmers possess (Woods, 2008). However, water is so valuable that farmers are beginning to sell their shares, rather than keeping them for their own use or entering into sharing agreements. After the completion of the Colorado-Big Thompson Project in the 1930s, 85 percent of the water shares were owned by agricultural interests. Currently, farmers only own 36 percent of these shares (Woods, 2008). Front Range Residents Colorado’s population has boomed to almost 4.8 million residents in recent years, and is one of the fastest growing states in the nation. The majority of this population resides in urban, suburban, and exurban areas on the Front Range (Jordan, 2003). The human manipulation and development of water in Colorado has allowed for a thriving population on the Front Range, and these residents heavily depend on water from the Colorado-Big Thompson Project (G. Wallace, personal communication, October 13, 2008). In order to sustain daily activities and home landscaping, the average Front Range resident requires 160 gallons of water per day (Jordan, 2003). Water Conflict 9 As a result of fears that the Front Range will one day reach a limit to the amount of available water, water conservation practices have become increasingly important to Front Range residents, particularly in the face of recent drought (“More people,” 2008). Cities, water districts, and non-profit organizations educate residents about the importance of conserving domestic water supplies. Western Slope Residents While the majority of Colorado’s population growth is occurring on the Front Range, the majority of Colorado’s water falls on the Western half of the state. As a result of the prior appropriation of water rights and the development of the Colorado-Big Thompson Project, Western slope residents often compete for the resources in their own backyard. Water conservation is particularly important to these residents, because they are the first to directly observe water shortages and changes in supply. Managers of the Colorado River District on the Western Slope are wary of excessive development on the Front Range. Manager Eric Kuhn expressed his concerns about the impacts of climate change and drought on Colorado’s water supply, proposing, “We really don’t know how much water we can develop at a reasonable risk” (“More people,” 2008, ¶ 11). Municipal Government While Colorado’s local municipal governments do not directly regulate water resources, their decisions significantly impact water use. Local governments develop land use plans for cities, counties and special districts. These plans guide decision-making, determine zoning of land, and regulate development projects. Planning commissions work closely with scientists, private developers, and public interests to approve or reject proposals that affect development. These governing bodies are challenged to balance residential and economic development with the protection of natural resources and open spaces in communities. Water Conflict 10 Private Developers Population development on the Front Range has produced a lucrative opportunity for private land developers. Because many of the developing exurban areas of the Front Range have permissive land use plans, private companies have the opportunity to develop land quickly and extensively for residential use (G. Wallace, personal communication, October 13, 2008). In order to develop land or build a new subdivision, developers must be able to provide water for their future residents. Typically, this means purchasing shares of water from other residential or agricultural users. The pressure that private developers place on the water market further increases the value of the resource and drives up prices. Northern Colorado Water Conservancy District The Northern Water Conservancy District (NCWCD) manages the Colorado-Big Thompson Project water supply for the northern Front Range. The NCWCD manages reservoirs for water storage and the distribution of water shares for domestic and agricultural use (Grigg, 2005). The members of the NCWCD board are not publicly elected, but the board still determines taxation of Front Range residents and allocation of resources for use. This limits the influence that residents and taxpayers can exert over the decisions made by the NCWCD (G. Wallace, personal communication, October 13, 2008). Resource Extraction Colorado contains a wealth of natural resources, which provide both economic opportunities and environmental challenges for the state. Resource extraction and mining provide jobs, revenue, and energy sources for Colorado. At the same time, resource development is often invasive and environmentally intensive, damaging wildlife habitat and spoiling scenic views. Water Conflict 11 Techniques for resource development require large water supplies. After use, this water is often too contaminated to safely return to streams and aquifers. This raises concerns about water quality, human health, and environmental degradation. Hydroelectric Energy The U.S. Bureau of Reclamation commissions water development projects across the United States. The generation of hydroelectric energy is among the goals of the Bureau. Because water is a continuously renewed resource, and since hydroelectric energy produces no emissions, it is promoted as a clean and efficient source of alternative energy. However, reservoirs, dams and other structures required for the generation of hydroelectric energy modify and impact rivers and land, threatening the natural state of these ecosystems (Jordan, 2003). Residential development on the Front Range requires energy resources that match the growing demands for electricity. With 14 hydroelectric power plants already producing over 700,000 kilowatts of electricity per year, water is an important energy source for the Front Range. Colorado’s abundance of rivers offers extensive opportunities for hydroelectric development, but this use may directly conflict with other water needs and values (Jordan, 2003). Environmental Conservation The establishment of the Instream Flow Program in 1973 was the first official recognition the importance of preserving the environmental quality of Colorado’s river systems (Hobbs, 2004). There are many groups that advocate for the conservation of the valuable ecosystem services, scenery and aesthetics, and critical wildlife habitat that rivers provide. Among these interested parties are local, federal and state public land managers, non-governmental or nonprofit environmental organizations, and concerned citizens. These conservation interests advocate for public policy and regulations that protect water resources, which maintain the environmental services of Colorado’s natural spaces. Water Conflict 12 Scientists The range of scientists involved in water conflict on the Front Range includes climatologists, biologists, ecologists and hydrologists. Research scientists collect and analyze data about water in the natural environment. Climatologists, for example, track amounts and patterns of precipitation to predict the amount of water that will be available for use annually. Field scientists directly observe the effects of water on organisms, ecosystems, and the earth. For instance, a fisheries biologist might view the impact of low stream flows on the health of native trout populations. Scientists provide input in public decision-making. Scientific consultants help draft Environmental Impact Statements for proposed development projects. Land use planning boards often refer to the advice of scientific “experts,” and scientists educate communities about the importance of water in sustaining the life of entire ecosystems. Because scientists can be very influential in Colorado’s water conflicts, they are important stakeholders. Recreation and Tourism Recreation and tourism is a multi-billion dollar industry in Colorado, and is the second largest contributor to Colorado’s economy (Jordan, 2003). From kayaking, rafting, wildlife viewing and fishing to skiing, snowboarding and snowshoeing, recreation in Colorado depends on water. In order to provide quality experiences for Colorado’s residents and visitors, water must be recognized for its recreational value. Kayaking and rafting require pristine and unobstructed rivers. Clean, accessible lakes and reservoirs are crucial for boating and fishing. Ski resorts often consume extra water to produce snow in the early winter (Nijhuis, 1999). These needs are often at odds with other uses of Colorado’s rivers, lakes, and water resources. Water Conflict 13 Regulatory Groups In Colorado, various departments and agencies govern and regulate water use, rights, disputes and issues. These governing bodies include: the Colorado Division of Water Resources, water courts, the Colorado Water Conservation Board, the Colorado Groundwater Commission, and the Water Quality Control Division, among others. These agencies and groups set water policy, settle litigation, enforce laws and standards, and guide the decisions of local water districts and municipal governments (Hobbs, 2004). Regulatory groups are not primary stakeholders in Colorado water conflict; however, they influence decisions and policy, so they are still an important party in this analysis. Relationships and Tensions The relationships between various parties involved in water conflict on Colorado’s Front Range are shown in Figure 1. Many of the parties depend on the services, influence the decisions, or have regulatory power over other parties. For example, private developers influence the land planning decisions of municipal governments, and municipal governments have the power to approve or reject private development proposals. The Northern Colorado Water Conservancy District (NCWCD) depends on the funding of taxpayers, and Front Range residents depend on the water services provided by the NCWCD. The map depicts other interrelationships as well. Alliances Alliances between parties exist to varying extents in Colorado’s water conflict. However, only major alliances are represented in the conflict map. The strong alliance between private developers and the NCWCD results from a common goal: providing water resources for domestic use to a growing Front Range population. The NCWCD funds water development Water Conflict 14 projects that supply water for the growing Front Range population, and developers purchase the rights for residents to use this water. Another mutually beneficial partnership is the alliance between conservation interests and scientists. Environmental conservation advocates rely on scientific research and data to establish the value of resource protection. Scientists provide factual information and lend credibility to land and resource managers. In turn, conservation organizations and agencies often provide employment and funding to field scientists and researchers. A final notable relationship involved in water conflict is the alliance between the resource extraction industry and hydroelectric energy production. These two groups share a primarily utilitarian value of natural resources; water is a resource that should be manipulated and used for the direct benefit of humans. Hydroelectric development and resource extraction both aim to maximize the opportunity for energy and fuel production offered by Colorado’s wealth of resources. Domestic Preference The oldest and most fundamental tension in Colorado water conflict occurs between agricultural and domestic interests (Conflicts 1, 2). Diversion rights are granted for either agricultural or domestic use, based on priority. However, in times of limited supply, domestic rights are preferred above agricultural rights, permitting Colorado’s residents to use a greater share of water than Colorado’s farmers. At the same time, agricultural production is Colorado’s primary economic industry, and farmers provide food for the residential population. The food, water and energy needs that accompany a growing Front Range population place extensive pressure on critical water resources. These tensions have historically and recently caused disputes over water allocation and consumption. Water Conflict 15 Trans-Mountain Diversions The Colorado-Big Thompson Project diverts water from the Western Slope for use on the Front Range, producing competition for resources between these two regions of Colorado (Conflict 3). Even in years of low precipitation, the Western Slope still has an obligation to supply sufficient water for domestic and agricultural use on the Front Range. Half of this foreign water is used for landscaping, rather than satisfying more basic domestic needs (Bates, Getches, Macdonnell & Wilkinson, 1993). This trans-mountain water diversion is a source of tension between stakeholders on both sides of the state. Environmental Conservation Environmental protection is the foundation of many persistent water rights conflicts. Conservation interests often conflict with agricultural land uses, population growth, resource extraction and energy production (Conflicts 4, 5, 6, 7 and 8). A high-quality natural environment produces healthy living conditions for humans, among other services, so the degradation of the environment directly impacts human health. More intensive land uses often damage or pollute the natural environment. Even with the designation of instream river flows as a beneficial water use, instream flow rights are difficult to obtain and enforce. The tension between preserving natural ecosystems and developing resources for human use has triggered litigation, water law violations, and hostility between various parties (G. Wallace, personal communication, October 13, 2008). Tourism pressures Recreational activities in both the summer and winter seasons heavily support Colorado’s economy and contribute to the quality of life Colorado residents enjoy. However, many recreational activities require unspoiled water sources. The rafting industry depends on flowing rivers with unobstructed rapids, and therefore opposes dams constructed for hydroelectric energy Water Conflict 16 development. Fishing demands clean and protected wildlife habitat in rivers and lakes, which may be drained or polluted by other uses. Conflict over water for recreation represents a struggle between both economic and environmental values. Conflict Map Summary The relationships, alliances and tensions depicted in Figure 1 offer a simplified representation of Colorado’s water conflicts. The disputes that result from conflicting needs and values often result in litigation, animosity and competition for resources. Because water conflict includes many stakeholders, resolving this conflict can be complicated. Diffusing tensions between parties and transforming hostile relationships into constructive partnerships require modern and creative approaches to conflict management. Management Recommendations Opportunities and Challenges While the expression “whiskey is for drinking, and water is for fighting” reflects the history of water rights issues in Colorado, this should not serve as a model for the future (Zaffos, 2008, ¶ 1). Water issues on the Front Range present both opportunities and challenges for transformative conflict resolution. Because of its complexity, water conflict is difficult to manage through traditional methods, such as negotiation. Rather, the investment of many stakeholder groups in water rights issues lends this conflict to collaborative resolution techniques. However, there are circumstances that impede collaborative approaches to conflict management. Barriers to the management of any environmental conflict may include a lack of time, money, or additional resources. The pressure of deadlines, the unavailability of participants, and insufficient funding may limit a collaborative process. Furthermore, if the participants have difficulty rejecting the status quo, or if they fail to recognize the value of this type of Water Conflict 17 participatory process, it will be difficult to sustain long-term management goals (Holman, Devane, & Cady, 2007). A long history of conflict has accompanied Colorado’s water law, and many of the involved stakeholders hold traditionally entrenched positions regarding the issue. Many of the tensions described in Figure 1 reflect hostility that has been present for decades. Legal battles characterize Colorado water law, in both the past and the present, and this polarization will be difficult to transform into constructive dialogue and cooperative thinking. Each stakeholder may represent another organization, posing another obstacle for conflict management. Since many of the affected parties belong to larger agencies, businesses, or other groups that hold official positions on issues, it may be challenging for individuals to separate themselves from their associations. In spite of these challenges, water conflict also offers opportunities for successful management and resolution. As pressure on water rights escalates with drought and resource scarcity, stakeholders are increasingly aware of the need for innovative solutions. While it may be natural for parties to refuse to collaborate until the “eleventh hour,” water issues are urgent enough that collaboration is now both acceptable and effective (Larmer, 2007, ¶ 4). Cooperation has been successful in managing water conflicts in the past, setting an example for current conflicts. The interstate water compacts between Colorado, Nevada, Nebraska and other states are a testament to the work of early water diplomats to build partnerships and relieve adversarial tensions between parties (Zaffos, 2005). Water issues necessitate creative problem solving, and these past achievements encourage the use of collaborative approaches in the management of current water conflict, as well. Water Conflict 18 Participatory Modeling for Conflict Management Successful conflict transformation requires the direct participation of all stakeholders (Maser, 1996). When the parties directly impacted by an issue are involved in recommendations and decision-making, rather than only government and regulatory agencies, they will be more invested in the decisions and outcomes (Beierle & Craford, 2002). Participatory modeling is an effective process for helping stakeholders communicate, learn, and work toward better conflict management. Participatory modeling is a process based on systems thinking, in which stakeholders collaboratively develop both qualitative and quantitative models of a conflict situation. The primary goal of participatory modeling is for all parties to develop a shared understanding of the conflict; communication that transcends the diatribe, persuasion, and accusations that typify traditional conflict is essential. This process validates the multiple stories that each individual offers, and aids in creating a comprehensive metastory that recognizes these various backgrounds and perspectives (Pierce & Littlejohn, 1997). Through joint learning, a group of individuals can make connections, discover common ground and gain an appreciation for the diverse values and perspectives of other key parties (Van den Belt, 2004). In participatory modeling, the participants design their own model of a dynamic system, using computer-modeling software. This interactive model integrates expert information with the experiences of each stakeholder. It is used as a tool to support dialogue, decision-making and planning for the future. The high degree of participation in the modeling allows stakeholders to develop ownership of the model and become invested in the future management of the conflict. The modeling process builds the capacity of the stakeholders to use the software to disseminate their learning and insights to others once the model is complete (Van den Belt, 2004). Water Conflict 19 This process is a particularly suitable approach to water conflict management in Colorado. The United States Army Corps of Engineers has used Shared Vision Planning, a form of participatory modeling, to better involve the public in water issues and decisions for more than a decade (Werick, 2000). Water conflicts have several dimensions, and this complexity can only be captured if the values and voices of all stakeholders are considered. Participatory modeling would increase the shared understanding about the causes of water issues for stakeholders, which would aid the development of innovative strategies for addressing the problem. This holistic approach to collaboration would emphasize the dynamics and resulting conflicts of the water rights system. A vision for the future is necessary, as water resources will become increasingly precious over time. If participants can reach consensus on the realities of the conflict, then they can move beyond current issues and decide how to more constructively manage conflict in the future. The Participatory Modeling Process Participatory modeling would proactively involve water conflict stakeholders in dialogue and problem solving. The following process is adapted for Colorado’s water conflicts from the structure proposed by Van den Belt (2007). A neutral facilitator is the most necessary component of a participatory modeling process. This facilitator manages the process, serves as the mediator of discussion, and acts as the recorder of all information. The facilitator may also aid in building the quantitative computer model, or an expert modeler may assist the model’s development. Because the participants create the model, and it belongs to every stakeholder involved, the modeler simply trains the participants and guides the process. Modeling would include up to 30 participants, representative of the many relevant stakeholder groups in the conflict. Water Conflict 20 The participatory modeling process for Front Range water conflict would last a total of five to seven working days. These days can be spread over any appropriate length of time, ranging from a week of workshops to years of collaborative work. The process is divided into three parts: preparation, workshops, and the follow-up and tutorial. Preparation. In the preparation stage of participatory modeling, the facilitator will assemble the group and conduct background research on the process. This will include the selection and invitation of key stakeholders, the collection of baseline information about each group and their perspectives of water conflict, and research on the history of the situation. When sufficient information has been gathered, the modeler and facilitator will work together to develop a preliminary model. The participants will either accept or reject this initial model later in the process. Workshops. The facilitator will conduct five workshops, each with a different purpose, to ultimately produce a complete model of Front Range water rights issues. The first workshop will provide an introduction for the parties involved. Stakeholders will meet each other, the facilitator and modeler will introduce themselves, and the group will establish ground rules for the process. These ground rules establish behavioral guidelines, expectations for the participants, expectations for the modeler and facilitator, and strategies for dealing with conflict that may arise. The facilitator will provide an overview of systems dynamic thinking and explain the modeling process to the participants. The modeler will introduce STELLA, the computer modeling software that participants will use to build the final model. In the second workshop, stakeholders will establish a baseline understanding of the conflict by defining water rights issues in Colorado. Participants will examine the history of the water rights system, water conflict trends, and the past behaviors of parties involved in the conflict. Once the participants have achieved consensus on the history of the problem, they will Water Conflict 21 envision an ideal future for water rights issues. The facilitator will ask participants to imagine the details of a future without conflicts over water on the Front Range, and each stakeholder group will have the opportunity to share their vision. In the third workshop, participants will build a qualitative model of the current water rights issues and conflict. By creating a preliminary map of the context and dynamics of the conflict, the participants will recognize the interrelationships and dynamics of the system. They will see how different parties behave, interact and influence one another. This model could be similar to the conflict map presented in Figure 1. In both qualitative and quantitative conflict modeling, the majority of the participants’ learning will occur when working together to build the models, rather than after the models are complete (Van den Belt, 2007). By the fourth workshop, the participants should be familiar and relatively comfortable working with one another. In this workshop, the participants will build the quantitative model of water conflicts on the Front Range, using the STELLA software. Prior to meeting, the group will develop a list of all the data necessary for designing the model, based on the qualitative model created in the third workshop. The participants, facilitator and modeler will gather data and invite experts to contribute information to the process. Participants will then transform the data into variables in the model and incorporate all relevant information that was collected before the workshop. The modeler will assist the participants in calibrating the model by setting reasonable parameters for the variables in the model. In the final workshop, participants will have the opportunity to fine-tune and manipulate the computer model. The modeler and facilitator will help build the confidence of the participants by establishing the validity and usefulness of the model. The group will create multiple scenarios, and will then compare the relative differences and tradeoffs between each hypothetical situation. Operating the model will empower the participants, and they will Water Conflict 22 continue to learn and develop insights about the issue. Following the manipulation of the model and analysis of various scenarios, the group will attempt to reach consensus on a list of recommendations for water conflict management. These recommendations will be based on the collaborative learning that has occurred throughout the five workshops. Follow-up and tutorial. The third stage of the participatory modeling process is a followup to the workshops and a modeling tutorial for the participants. A written report will present the participants’ final model and summarize the results of the process. The modeler and facilitator will conduct a tutorial for the participants to empower stakeholders to communicate their results to a wider audience. Participants will present the model to their respective organizations, including their coworkers and superiors. The results will also be disseminated to any governing or regulatory bodies that could benefit from the recommendations of the group. By conducting individual interviews with each participant, the facilitator will evaluate the effectiveness of the process in improving the shared understanding of water conflicts, building relationships among the participants, and transcending the polarization and antagonism of traditional water conflict. From these interviews, observations of the process, and other forms of ongoing evaluation, the group will be able to measure the short-, medium-, and long-term success of the participatory modeling process. Anticipated Results and Outcomes Participatory modeling has the potential to yield many positive outcomes and improve the overall dynamics of water conflict. The team learning and interactions between participants will help the stakeholder groups build relationships that overcome social barriers and historic disputes. Constructive discourse about water conflict will help stakeholders recognize diverse needs, values and motivations; this will prevent them from dehumanizing the decisions and Water Conflict 23 actions of other parties, and it could diffuse tensions within the situation (Pearce & Littlejohn, 1997). The creation of the computer models allows for creative problem solving, which could result in more acceptable solutions to water rights problems in Colorado. Because the conclusions the participants make will have been developed collaboratively over a length of time, the recommendations for the future could be more thoughtful and innovative than those yielded by traditional approaches. These recommendations would potentially support policy and management decisions that can further transform water rights issues. The final computer model will serve as a valuable communication tool beyond the modeling process. Participants will deliver the model to their organizations, extending the learning that occurred throughout the modeling. The model is flexible and can continue to be modified in response to future circumstances and policy decisions. The adaptability of the model will facilitate continued learning about Colorado’s water conflicts. Stakeholder groups and individuals can continue to build and change the model to anticipate future scenarios and develop management strategies, sustaining its effectiveness as an educational instrument. Conclusion Water conflict is a central issue in Colorado. The increasing demand for limited water resources over time has intensified the competition for water rights, and this tension has resulted in innumerable conflicts. However, traditional conflict management strategies have done little to diffuse or reduce conflict; rather, water conflict continues to escalate. Progressive approaches must transform negative, competitive interactions between stakeholders into constructive, successful partnerships. The needs and motivations of every stakeholder are valuable, and these diverse perspectives deserve recognition. A participatory modeling process would facilitate a collective understanding of water conflict on the Front Range while promoting mutual respect Water Conflict 24 among stakeholders. Through collaborative learning and computer-aided modeling of the water rights system, stakeholders would gain a holistic understanding of the water conflict story. The dialogue and recommendations that result from participatory modeling could encourage transformative, innovative and viable water rights decisions for the future. Water Conflict 25 References Bass, R. (2007). Foreword. In G. Wockner & L. Pritchett (Ed.), Pulse of the River (pp. IX-XIII). Boulder: Johnson Books. Bates, S. F., Gethes, D. H., Macdonnell, L. J., & Wilkinson, C. F. (1993). Searching Out the Headwaters: Change and Rediscovery in Western Water Policy. Washington: Island Press. Beierle, T.C. & Craford, J. (2002). Democracy in Practice: Public Participation in Environmental Decision Making. Washington: Resources for the Future. Fisher, S., Ibrahim Abdi, D., Ludin, J., Smith, R., Williams, S., & Williams, S. (2000). Tools for Conflict Analysis. In Working with Conflict: Skills & Strategies for Action (pp. 17-35). New York: Zed Publishing. Grigg, N. (2005). Citizen’s guide to where your water comes from. Denver: Colorado Foundation for Water Education. Hobbs, G. J. Jr. (2004). Citizen’s guide to Colorado Water Law. Denver: Colorado Foundation for Water Education. Holman, P., Devane, T. & Cady, S. (2007). The Change Handbook: The Definitive Resource on Today’s Best Methods for Engaging Whole Systems. San Francisco: Berrett-Koehler Publishers. Jordan, E. (2003). From Peak to Prairie: Colorado’s Water at Work. Sterling: Centennial Soil Conservation District. Larmer, P. (2007, May 14). When the going gets tough, the tough collaborate. High Country News [Paonia]. Retrieved October 20, 2008, from http://www.hcn.org. Nijhuis, M. (1999, January 18). Keystone snowmakers get thirsty. High Country News [Paonia]. Retrieved October 1, 2008, from http://www.hcn.org. Maser, C. (1996). Resolving Environmental Conflict: Towards Sustainable Community Development. Delray Beach: St. Lucie Press. More people using shrinking resource (2008, September 20). KMGH [Denver]. Retrieved October 1, 2008, from http://www.thedenverchannel.com. Pearce, W. B. & Littlejohn, S. W. (1997). Moral Conflict: When Social Worlds Collide. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications. Van den Belt, M. (2004). Mediated Modeling: A Systems Approach to Environmental Consensus Building. Washington: Island Press. Water Conflict 26 Werick, W. (2000). History of Shared Vision Planning in the Army Corps of Engineers. In Shared Vision Planning. Retrieved November 15, 2008, from http://www.sharedvisionplanning.us Woods, H. (2008, April 25). Water most valuable crop for Northern Colorado farmers. The Coloradoan [Fort Collins]. Retrieved October 1, 2008, from http://www.coloradoan.com. Zaffos, J. (2005, March 21). The life of an unsung Western water diplomat. High Country News [Paonia]. Retrieved October 20, 2008, from http://www.hcn.org.