op-ed contributor

advertisement

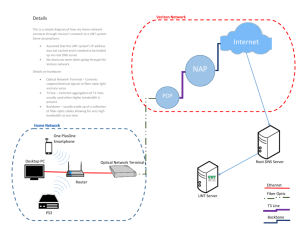

1 OP-ED CONTRIBUTOR Static on the Dream Phone By TIM O’REILLY Published: December 15, 2007 SEBASTOPOL, Calif. E David Plunkert THE Internet and the cellphone are on a collision course. In the future, the cellphone and similar wireless devices, not the personal computer, will be the primary interface to the cloud of information services that we now call the Internet. The demand for Internet-style applications on the phone — e-mail, maps, photo and video sharing, social networking and even Internet telephony — is exploding. Meanwhile, cracks are appearing in the control that cellular carriers have long held over their networks. Verizon announced last month that it will open its network to “any application and any device” by the end of next year. But while Verizon’s pledge sounds promising, the language in which it is couched makes me wonder whether Verizon understands what a true open platform looks like. The announcement states that “the company will publish the technical standards the development community will need to design products to interface with the Verizon Wireless network,” and that “devices will be tested and approved in a $20 million state-of-the-art testing lab.” It’s not yet clear what 2 standards developers will need to follow to write applications that work with both the device and the network, and who will control those standards. This is not “open.” It’s just a little less closed. A true open platform like the Internet doesn’t have certification of trusted devices or applications. Developers get to do anything they want, with the marketplace as their only judge and jury. Both the personal computer and the Internet flourished in an environment of free-market competition. Tim Berners-Lee did not have to submit his idea for the World Wide Web in 1991 to a “state-of-the-art testing lab.” All that he needed to unleash a revolution was a single other user willing to install his new Web server software. And the Web spread organically from there. There’s a lesson here for Verizon and other cellphone companies. Like the open architecture of the personal computer, the open architecture of the Internet didn’t mean the end of competitive advantage. What we learn from the history of both is that open platforms engender “winner takes all” network effects. Once a company gets a first-mover advantage, the mass of users adopting the company’s application or platform makes that product more attractive to the next user. The free-for-all that I.B.M. started in 1981 when it published the specifications for a personal computer that anyone could build ended up with Microsoft as the dominant software provider for the PC. The online free-for-all of the ’90s and early ’00s is leading us in the direction of dominance by a few huge companies that have learned the new rules of the Internet economy. For the current generation of Internet applications, sometimes referred to as “Web 2.0,” the data collected from users is the true source of competitive advantage. And the first movers, the companies that understand and apply this insight, have services that get better fast enough that their competition never catches up. The power of a social network like MySpace or Facebook isn’t in its software or its control over which applications get on its platform. It is in the critical mass of participating users. Ditto for eBay, Skype or YouTube. Even less obvious cases like Amazon, where user annotation makes for the best product catalog in the world, and Google, whose search index and ad auction are both driven by user 3 participation, show the power that comes from harnessing the collective activity of everyone who uses the service. Cellular carriers need to embrace this insight. Winner-take-all profits can be achieved by opening up their networks and then harnessing community contributions (including the contributions of software developers) to improve — or invent — new services. Google is trying this with its new Open Handset Alliance, which combines an open-source phone platform with an Internet-style application development model. Imagine, for a moment, that Verizon were to think like Google or Amazon. It could give you access to your entire call history, every phone call you have sent or received, not just your last 10 phone calls. It might build an address book for you based on everyone you had ever talked to, with top results for the numbers you call most often. And what if this phone company opened up its databases to developers of software applications? We could soon see mash-ups of your call history with the address books from your personal computer, your telephone and your social network. Now imagine a user community turned loose to annotate that data. Consumers would flock to the best software, made by independent developers that a cellular network would enable by building a true Internet-style open platform. Goodbye to user-unfriendly service contracts as a way to keep customers captive. Who would switch carriers when so much knowledge about your social network resided on your phone company’s servers? In short, the race is on for competitive advantage in the truly open cellular phone network of the future. Verizon hasn’t moved far enough — yet. If the cellular carriers don’t act, Google and its partners will beat them to the prize. Tim O’Reilly, a publisher of computer books, is the co-producer of the Web 2.0 conference.