Teaching about Hinduism-Challenging issues

advertisement

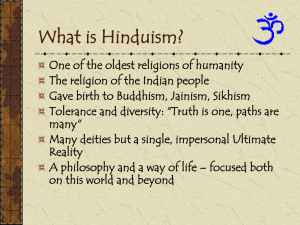

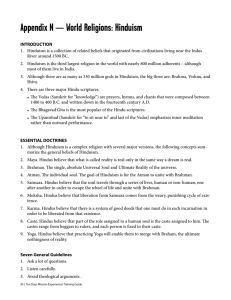

Teaching about Hinduism: Some Challenging Issues Lynne Broadbent Why is Hinduism challenging? Hinduism has been called ‘infinitely fascinating, surprising, and challenging’. If the religion itself is regarded as challenging, then teaching about it is certainly a challenge for the teacher in the primary classroom! Hinduism is the most ancient of all the religions, with no one moment of divine revelation such as at Jesus’ baptism or the Angel Jibril’s revelation to Muhammad, no one key figure or founder, a baffling array of images of the divine and numerous holy books. Therefore, some of the basic starting points through which a teacher might introduce a new religion to pupils are not quite so straightforward when it comes to Hinduism – but maybe it is this which makes Hinduism fascinating, surprising and challenging for pupils. How many gods? One god – or many gods? Talking about God is never a simple matter, and teaching about the concept of God in Hinduism presents three immediate challenges: first, the question of number- is there one god or thousands of gods? second, the question of visually representing god, in pictures or images, referred to as ‘murtis’, for display on home shrines and in the mandir; and third, there is the nature of the images, or murtis, themselves, brightly coloured and richly symbolised images of male, female and animal deities, a challenge to the viewer’s cultural as well as religious understanding. For Hindus, there is One Ultimate Reality, Brahman, described as ‘Sat-citananda’, Truth, Consciousness and Bliss. For Hindus, as for most religious adherents, God is far greater than human powers of description, so Brahman is described in wide-ranging and seemingly contradictory terms; Brahman is therefore both immanent and transcendent, personal and impersonal, male and female, having form yet being formless. Most, but not necessarily all, Hindus will understand this One Ultimate Reality as a personal God who is experienced through God’s three main functions in the world; so God is a Creator, a Preserver and a Destroyer. These three functions or qualities of God are represented by three images; Brahma the Creator, Vishnu the Preserver or Sustainer and Shiva the Destroyer, that is a destroyer of evil. Although shown as separate images and functions, the three aspects of the Divine are interrelated as the world is constantly in a motion of being created, sustained, destroyed and then being re-created. While Brahman as Ultimate Reality and the different representations of God may seem baffling, some scholars have used a comparison of light passing through a prism: the ‘white’ light enters the prism and is refracted into the many colours which make up that white light. So it is with Brahman, all the aspects or qualities which make up the Divine are seen through the different images. Brahma, the Creator, is often shown with several heads and arms, a symbol of his creative power; Vishnu, the Preserver, often shown holding a white conch shell and a rotating wheel, is sometimes regarded as a ‘cosmic policeman’ for when there is an imbalance between good and evil in the world, he sends down an incarnation (avatara) to redress the balance and Rama and Krishna were two of his incarnations; Shiva the Destroyer is often pictured as Lord of the Dance, dancing in a circle of flames and stamping on the demon of ignorance. How do Hindus represent the Divine? The representation of the divine in Hinduism has developed over many thousands of years and is completely at odds with Jewish and Muslim practice where the representation of God is forbidden. However, the question of representation raises a basic human issue and that is, how do you speak of and make sense of the divine and express your relationship with the divine when the divine is unseen and transcendent? Jews convey their relationship with God through constant recitation of God’s saving actions in their history, and in synagogue liturgy there is frequent reference to ‘I am the Lord your God who brought you out of the land of Egypt’. Muslims express their relationship with Allah through recitation of the 99 Names of Allah, for example, ‘The Creator’, ‘The Guide’, ‘The All-Forgiving’ and ‘The Source of Peace’. Christians express their relationship with the divine through reference to three images, the Father, Son and Holy Spirit, the second of these, the Son, being represented visually in homes, churches, on posters and greetings cards. Hindus visually represent the different attributes and qualities of the divine. As for the strangeness of the colourful and highly symbolic Hindus images – this seems exaggerated because we often fail to draw on the rich diversity of images and cultures when teaching about Christianity. If we were to familiarise our pupils with Greek and Russian icons, with huge sparkling golden images of Christ Pantocrator spanning the domes of churches, and Chinese and African images of Jesus, then encounters with Hindu deities might not seem so strange. How can we address the challenge of teaching about the Hindu concept of God? Many teachers begin with an AT2 or Learning from… religion task which could be used with any religion – that is asking pupils to describe themselves in a limited number of words. Having described themselves as daughter, sister, cousin and friend and their personal qualities such as their friendliness, reliability, ‘a good listener’, trustworthy … , most pupils come to the realisation that a limited number of words is insufficient to describe their attributes! And so it is with God! Looking at an array of Hindu deities, the images may at first seem strange but the more familiar the images become, pupils start to see past the ‘strangeness’ and begin to identify and discuss the specific symbols and in turn the qualities which the symbols represent. So the many arms shown on several deities are recognised as symbols of God’s power, the blue colour of Krishna a symbol representing the sky and the ocean, a symbol of the infinite nature of God, Shiva’s hour-glass drum, a symbol of rhythm and sound as Shiva beats out the rhythm of the universe. Clarification on the meaning behind the symbols can be sought though textbook, internet and cd-rom and before long, pupils are developing skills of investigation, interpretation, discussion and reflection, in this case, reflection on the nature of God, all skills which transcend the teaching of Hinduism and skills which lie at the heart of good RE. Surely there are too many gods and goddesses and the children will not understand? Further exploration of the stories and rituals associated with the deities unlocks the ways in which Hindus both interact with and learn from the divine. One of the more familiar deities is that of Ganesh with his elephant’s head. The story tells that Ganesh is the son of Parvati, moulded from skin from her own body and created to satisfy her desire for a child. As a young boy, Ganesh is guarding the room where his mother is taking a bath when his father, Lord Shiva returns. Not recognising his son, Lord Shiva is angry when he finds his way to Parvati’s room barred and in anger he cuts off Ganesh’s head. Of course, as a god, Lord Shiva can restore his son to life again when faced with Parvati’s grief and does so with the head of an elephant. Just as elephants remove any obstacle in their path, Ganesh becomes known as ‘the Remover of Obstacles’, the aspect of the divine prayed to before participating in worship in the mandir, before moving house and before an examination or any other important event. If this appears strange to pupils at first, then they need to reflect on whether in other religions people pray to God to help remove their difficulties or obstacles – and then things are not so strange! Lakshmi, the Goddess of Wealth and Good Fortune is particularly worshipped at Divali, a Hindu New Year festival. Lakshmi is usually depicted seated or standing on a lotus flower a symbol of purity and goodness rising from the murky waters below: in one of her four hands she holds a lotus flower, from another hand fall gold coins symbolising wealth and prosperity. Businessmen pray to her at Divali, the start of the new financial year. Krishna is another popular deity, worshipped both as a divine child and as an adult. His birth is celebrated each year when a murti or image of him is placed in a swing and rocked by each member of the congregation. Stories of him as a child include him stealing his foster mother’s butter and another of him revealing to her an image of the whole universe, the sun, the moon and the stars, in his mouth. Krishna is the playful and captivating aspect of the Divine – the God who attracts others to him. But it is in the story of Krishna and Arjuna told in the Bhagavad Gita that we see God as both friend and teacher we he teaches Arjuna, a human, how life should be lived. Arjuna, in his chariot and about to go into battle, sees that if he proceeds then he will be fighting his own relatives. The Bhagavad Gita describes his plight: ‘Life goes from my limbs and they sink, and my mouth is sear and dry; a trembling overcomes my body, and my hair shudders in horror..’ (BG 1:29) Arjuna comes to recognise that his charioteer is none other than Krishna, and Krishna calls Arjuna ‘friend’ and teaches him about dharma, living one’s life according to one’s spiritual duty. Praying to Ganesh to remove any obstacles, praying to Lakshmi for wealth and good fortune and learning from Krishna the ways to live one’s life are just some expressions of the relationship between humans and the divine which can be the focus of learning for Key Stage 1, 2 and 3 pupils. In the story of Divali, the key characters, Rama, Sita and Hanuman, display particular qualities or values and act as ‘role models’ for those who listen to the story. Rama, for instance, one of the incarnations of Vishnu, symbolises strength and the devotion of a husband as he rescues Sita from the demon Ravana; Sita is the faithful wife and Hanuman, the monkey god, is the devoted follower and friend of Rama. Work on Divali can therefore a consideration of the personal qualities and values it promotes. The Gods, are they real? Encounters with stories and visual images of the Divine invariably lead to questions about ‘truth’ and, as when asked about any religion, this is a difficult question. If the question in part focuses on whether Hindus believe that there was ever a time in history when God lived on earth, then the answer is ‘yes’ for Hindus believe that Krishna was born in Mathura, Northern India, and grew up in the town of Vrindavan, a place of pilgrimage today. If the question relates to whether Hindus believe that the Divine is effective in the world today and that it is ‘worthwhile’ praying to God for help and guidance, then again the answer is ‘yes’ and there are several ways to enable pupils to understand this. First, resources such as the ‘Gift to the Child’ interactive story books designed for Foundation Stage pupils show children in worship scenes and discussions, with, for example, Kedar, a young Hindu boy seen worshipping Ganesh. Second, there is no better way to encounter the impact of the Divine on Hindus’ lives than to witness ‘puja’ or worship in a Hindu temple or mandir. Mandirs can look very different from each other depending on the particular religious and cultural traditions which they represent, but in most there will be a bell, rung by worshippers to alert God of their presence and an image or murtis of Ganesh before which worshippers pray with hands together and bowed heads as soon as they enter. A central shrine or shrines will house murtis of perhaps Rama and Sita, or Krishna with his consort Radha, and during the arti ceremony, the flames of the arti lamp will be waved in front of the deities and then offered as a blessing to the worshippers. From the rituals and the responses of the worshippers, it is apparent that for Hindus the murtis are more than just symbols of the deity: when the murtis in the mandir are consecrated, the priest invites the deity to be present within the murti and the murti becomes the living presence of the deity. For Hindus then, to worship in the mandir is to come face-to-face with the living presence, to see and be seen by God; this ‘seeing’ is called ‘darshan’. Third, in the absence of a visit to a mandir, the use of video may serve to convey the personal nature of God in the Hindu tradition through images of worship in a mandir or daily pujs (worship) at a home shrine where the lights of a diva, flowers, fruit and incense are offered to the deities. Summary Syllabuses for Religious Education indicate a range of approaches to teaching and learning about Hinduism, from the study of its holy books (reference has already been made to the Bhagavad Gita with the Krishna and Arjuna story and the story of Rama and Sita, found in the Ramayana), a study of karma and reincarnation (closely linked to following one’s dharma as in the Krishna and Arjuna story), an exploration of moral values and even a study of the caste system – which is strange, since some Hindu writers comment that it is no longer strictly adhered to in Hindu society! However, the greatest challenge in teaching about Hinduism is also probably the greatest contribution which teaching about Hinduism can make to programmes of Religious Education, that is the opening up of discussion about the existence and the nature of god, a discussion with begins with Foundation Stage pupils as they hear the story of Rama and Sita and continues into VI Form philosophical debates!