edwards_6e_Feb04

advertisement

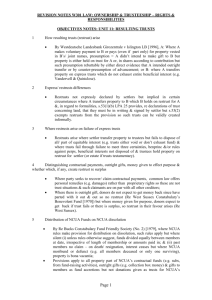

UPDATE FOR 6TH EDITION OF BOOK TO 02.04 Chapter 4 P114 Further Reading J. Garton: "The role of the trust mechanism in the rule in Re Rose. " Conv (2003) 364-379 Chapter 9 p232 It was announced in the Queen's speech, that a draft bill is to be published introducing the changes to charity proposed in the Strategy Unit's report, "Private Action, Public Benefit". (See the last website update), The draft bill is awaited. p233 Further Reading P. Hamlin: "Charities and the Human Rights Act - a progress report" PCB (2003) No.5 369-372 M. Scott and V. Benson: "Prospective changes in charity law" NLJ (2003) Vol.153 (Charities appeals supplement) Pages 4,6 F. Mactaggart: "Reforming charity" SJ (2003) Vol.147 No.47 Supp (Charity & appeals supplement winter 2003/04) Pages 23,25 Chapter 10 Page 245 RAVI VAJPEYI v SHUIB YUSAF (2003) (LTL 24/9/2003 is a first instance decision which centres on the presumption of resulting trust and its rebuttal. In the case a property was conveyed into the sole name of Y. V and Y were in a relationship but were not married. (V was already married to someone else.) In 1980 a property was bought for £29,500 as an investment and to let out. Y was a student at the time of the purchase but was anxious to get a foot onto the property ladder. Y raised a £20,000 mortgage. V provided the balance of the purchase price and paid for the legal fees, stamp duty etc. This amounted to £10,000. V, who was some 12 years older than Y and already owned a property, borrowed the £10,000. The relationship between Y and V continued despite V entering an arranged marriage which subsequently ended in divorce. Then, in 1994 the relationship broke down. In the instant case V claimed that the property was held by Y on a resulting trust for herself (V) and Y. On the basis of the alleged contribution (£10,000) a 33.98% share was claimed by V. It was held that there was a presumption that the property was bought by Y on trust for himself and V. This presumption, the courts said, was not a strong one in all the circumstances of the case and that it had been rebutted by Y. The £10,000 was a loan and not a contribution to the purchase entitling V to a share in the ownership. One factor that influenced the decision was the amount of time that elapsed before the alleged trust was asserted. V had not claimed the rents or a share of the property for 20 years. If V considered she had an interest in the house, surely she would have claimed a share of the rents? The court considered that “the common sense of the situation” pointed to there being a loan. Given the respective situations of Y and V it could be thought probable that V used her position and good credit rating to raise the money to help Y to buy the property rather than intending to contribute to the purchase price and to obtain an interest in the property. In this case the court considered that the presumption was not strong. An example of where the presumption might be “fairly strong” was given. This was in the case of a young couple intending to buy a house in which they would live and where they both contributed to the purchase price. An example of a weak presumption was also given. This was the case of a young person, in her first job who wanted to buy a house in which to live but, because of a “low” salary was not able to raise sufficient money. If a rich relative contributed to the purchase the “common sense” explanation would be that the contribution was intended to be a loan. Chapter 11 p268 The fiduciary position of directors, as well as the distinction between personal and proprietary remedies (see pp277 and 431) have recently been considered in Clark v Cutland [2003] 4 All ER 733 in the Court of Appeal P and R were equal shareholders and the only directors of a company. R made unauthorised payments to himself from the company of £145,000, which he paid into his pension fund. The issue in the Court of Appeal was whether this sum could be traced into the pension fund and recovered, by means of a charge on the fund. (The company had been held to owe other money to the fund and P wished to set off the £145,00 against this). As in Guinness v Saunders, the payment to R by himself had clearly been made without the company's authority and in breach of the company's articles. This made the payments to the pension fund void and of no effect. However, the claim to trace the money was made on the basis of constructive trust, and so it made no difference whether the payment was void or voidable. The crucial factors were that R had made the payment in breach of his fiduciary duty, and that the pension fund trustees now had notice of the company's claim. P had previously conceded that the pension fund trustees would not be personally liable, but this was also held not to be relevant to the proprietary claim. It was accepted that the Trustees did not have sufficient (or indeed any) knowledge of the breach of duty, and so could not be personally liable, but that did not prevent tracing to them as innocent volunteers. A charge on the pension fund for the £145,00 was the appropriate remedy. p299 Further Reading G. Andrews: "The redundancy of dishonest assistance" Conv (2003) 398-410 S. Elliott & C. Mitchell: " Remedies for Dishonest Assistance" 64 MLR (2004) 16-47 Chapter 12 Page 323 Buggs v Buggs (27 June 2003) [2003] EWHC 1538 (Ch) This is not a case on a family home but the “principles” outlined by Lord Bridge in Lloyds Bank v Rossett were relevant to the decision. H and W were married in August 1980. In 1987, H’s mother obtained the right to buy a council flat for £14,560. The greater part of the purchase money was provided by H and W. The title was in the sole name of the mother. H’s mother lived in the flat and it was never the matrimonial home of W and H. 1997, H and W divorced. In August 1999, the H’s mother died. H was named as the sole executor of her will. H wanted to sell the flat. W sought a declaration that she was entitled to a share in the flat on the basis that she had contributed to the purchase price of the property and, she claimed, there had been a common intention that the property would be held on trust for her and H jointly. The claim was dismissed. The judge, referred to Lloyds bank v Rossett in which Lord Bridge outlined the two distinct routes to proving a beneficial interest. ((i) evidence of an express agreement and (ii) where, although there is no evidence of an express agreement, the conduct of the parties provides the basis from which the court can infer an intention to share the property.) Although it was probable that the issue of what was to happen to the house on the death of H’s mother had been discussed by H and W and it was accepted that the plan was that after H’s mother's death the house should belong to H and W’s household, that did not, the court decided, amount to an agreement that W would have a share in the ownership of the flat. Page 331 The Queen’s speech contained a reference to introducing a bill to give equal partnership rights to homosexual couples but at the date of writing this update the bill has not been published. D Burles, Promises, promises" - Burns v Burns 20 years on Family Law Fam Law (2003) No.33 November Pages 834-839 M Pawlowski Fair shares? Solicitors Journal SJ (2003) Vol.147 No.43 Pages 1301-1303 M.P Thompson, The obscurity of common intention Conveyancer and Property Lawyer Conv (2003) September/October Pages 411-424 Chapter 16 p434 The proprietary liability of third parties who had received money improperly obtained and subject to a constructive trust was considered by the Court of Appeal in Clark v Cutland. A fuller discussion of the case is to be found under Chapter 11 above. p437 The case of Russell-Cooke v Prentis [2003] 2 All ER 478 has again emphasised that the rule in Clayton's Case is only a prima facie approach, which can easily be displaced upon evidence of the parties' intention. Accordingly, the contributors in an investment scheme in this case were presumed to have expected their contributions (which went into a bank account) to form a common fund out of which investments would be made. "First in first out" was therefore inappropriate, all contributors ranked equally and a distribution pari passu of remaining money in the fund was ordered. Chapter 18 P492 The concept of undue influence was discussed by the Court of Appeal in Jennings v Penny Cairns [2003] EWCA Civ 1935 where it was held that the appellant was obliged to repay the deceased's estate the money she had received, because she had failed to ensure that a gift from her aunt was made only after a full and informed choice, even though the appellant was not responsible for the misleading or wrong advice given to deceased.