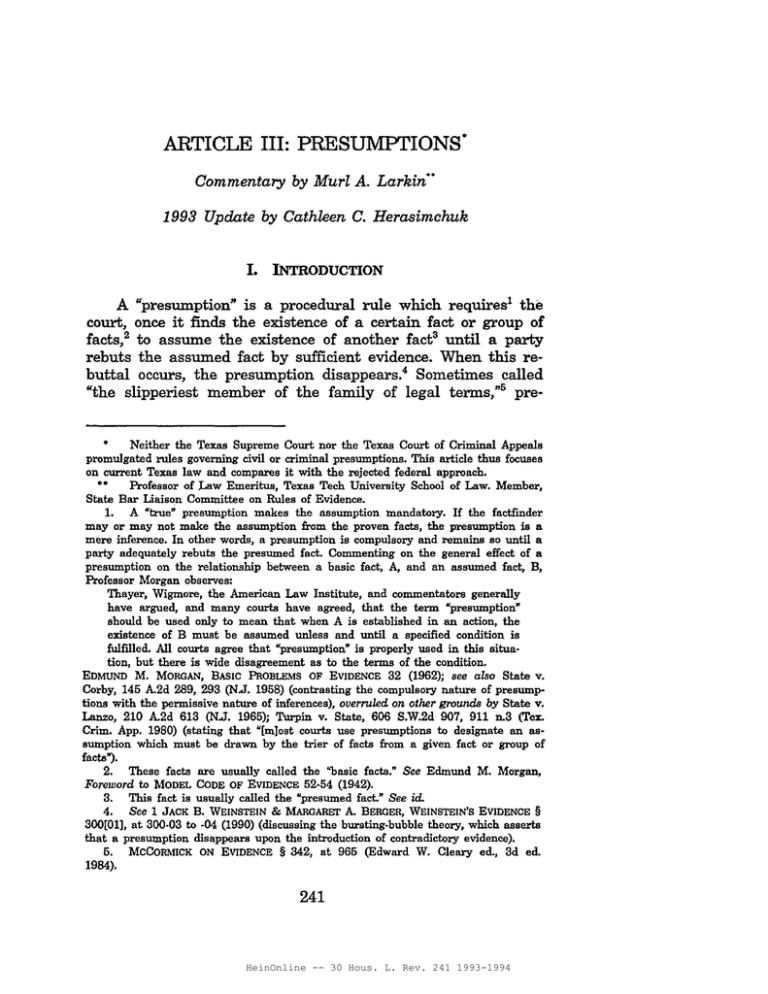

ARTICLE III: PRESUMPrIONS· Y. Commentary by Murl Larkin··

advertisement