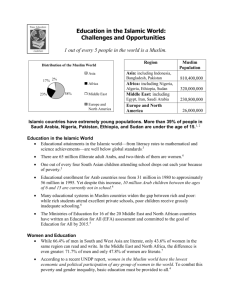

Encouraging Muslim women into higher education through

advertisement