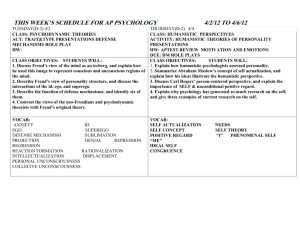

Mod25PsyHumanPers.A4

advertisement

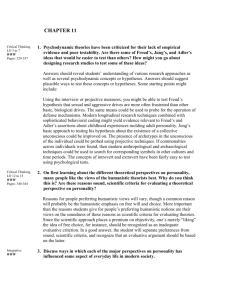

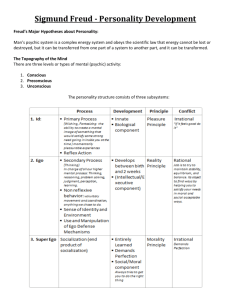

Module 25: Psychodynamic & Humanistic Perspectives [Ernst] 1. Psychodynamic Perspective a. Freud’s Psychoanalytic Theory i. Personality Structure ii. Defense Mechanisms iii. Personality Development iv. Assessing the Unconscious b. Neo-Freudians i. Alfred Adler ii. Carl Jung iii. Karen Horney c. Evaluating the Psychodynamic Perspective 2. Humanistic Perspective a. Abraham Maslow and Self-Actualization b. Carl Rogers and the Person-Centered Approach c. Assessing Personality and the Self d. Evaluating the Humanistic Perspective What is “personality”? I hear students use this word all the time. Meredith likes how J.J. looks but laments, “If only he had a personality.” And for those who don’t suffer J.J.’s problem, personalities have been labeled everything from “rotten” to “winning.” These everyday notions of personality are fine for discussing friends between classes or at lunch, but psychologists use the term “personality” more carefully. 1 Psychologists define personality as an individual’s characteristic pattern of thinking, feeling, and acting. In this module, we’ll consider the psychodynamic and humanistic perspectives, two very different theories about how personality develops and how it can be assessed. Psychodynamic Perspectives After going out for three months and then breaking up, Tyler says, “I know I’m in denial, but I think we’ll get back together.” Julie refuses to talk about a past relationship, saying she doesn’t remember much about it. “I’ve repressed that whole thing.” In a class full of ill-mannered students, the teacher might say, “You’ve all regressed to 8th grade.” These three terms, denial, repression, and regression, all used by people who may not have studied psychology, can be traced back to psychology’s first, and most famous personality theory, Sigmund Freud’s psychoanalysis. Freud believed unconscious motives and unresolved childhood conflicts (many of them sexual) produce our characteristic thoughts and behaviors. Between 1888 and 1939, Freud published 24 volumes of material on his theory. Today, the strict psychoanalytic perspective has mostly given way to the more moderate psychodynamic approaches. These theorists do share Freud’s belief that many of our thought processes occur unconsciously, and that childhood experiences affect our adult personalities. However, they are less likely than Freud to dwell on unresolved childhood conflicts and more likely to consider today’s inner struggles. Yet, thanks to persisting Freudian popularity in “pop” psychology, you are more likely to be familiar with Freud’s outdated terminology than almost anyone else we introduce in this book! In this module, I will outline Freud’s original ideas so you know how the buzz got started. 2 Freud’s Psychoanalytic Theory What’s the Point? What were the key elements of Freud’s personality theory? Sigmund Freud was an Austrian physician who noticed that some of his patients’ problems seemed to have no physical origins. A neurologist in France who was treating patients using hypnotism intrigued Freud. Hypnotism is a social interaction during which a hypnotist makes forceful suggestions to a subject. Freud was amazed to find that some patients’ physical symptoms disappeared after the hypnotic experience. Freud experimented with hypnotism, but found that some patients could not be hypnotized. As an alternative to hypnosis, Freud asked his patients to free associate their thoughts by relaxing and saying whatever came to their minds regardless of how trivial or embarrassing the statements seemed. Using free association and other techniques, Freud believed he could tap into the patient’s unconscious, which he believed was a reservoir of mostly unacceptable thoughts, wishes, feelings, and memories. If the unconscious could be reached, Freud believed painful childhood memories could be uncovered and healing could occur. Freud saw personality as a big iceberg consisting of three parts: unconscious, conscious, and preconscious. Just as the majority of an iceberg is below sea level and unseen, Freud felt that most of personality was unconscious and hidden from view. The conscious mind, the thoughts and feelings we’re aware of is represented by the visible part of the iceberg above sea level. Freud also believed there was a preconscious just below the water line, consisting of the thoughts and memories that are not in our current awareness, but are easily retrieved. (Figure 25.1). 3 For Freud, treating those with psychological disorders meant revealing the nature of one’s inner conflicts so that tensions could be released. He used free association and dream analysis to catch glimpses of the unconscious. Freud also thought the unconscious could be revealed by carefully observing people’s habits and listening to their “slips of the tongue.” These “Freudian slips” as they are often called are supposed misstatements reflective of something you’d like to say (Figure 25.2). Underlying Freud’s view was the idea that personality grows out of the conflict between our pleasure-seeking biological impulses and the internalized social roadblocks restraining us. Resolving this conflict, he believed, shapes the structure of your personality. Personality Structure What’s the Point? How do id, ego, and superego interact, according to psychoanalytic theory? According to Freud, you have a healthy personality if you successfully resolve the conflict between social restraints and pleasure-seeking impulses. Success means expressing these impulses satisfactorily while avoiding punishment or guilt. This conflict involves the interaction of three, abstract psychological concepts that Freud believed help us understand the mind: • The id, present at birth, consists of unconscious energy from basic aggressive and sexual drives. Operating from the pleasure principle, the id demands immediate gratification. For instance, a newborn cries for whatever it needs, whenever it needs it, regardless of what anybody else wants or needs. 4 • The superego consists of the internalized ideals and standards for judgment that develop as the child interacts with parents, peers, and society. It is the voice of conscience that focuses on what we should do, not what we’d like to do. The superego wants perfection, and those with a weak superego are likely to give into their urges and impulses without regard to rules. On the other hand, an overly strong superego often produces someone who is virtuous yet guilt-ridden. • The ego is the mediator that makes decisions after listening to both the demands of the id and the restraining rules of the superego. Operating from the reality principle, the ego satisfies the id in a realistic way that does not lead to personal strife. The ego, Freud thought, represented good sense and reason. Roughly speaking, some have said the id is the “child” in you, the superego “your parent,” and the ego “the adult” that results from the mix. Defense Mechanisms What’s the Point? According to Freud, how are defense mechanisms helpful? Anxiety, wrote Freud, is the price we pay for living in a civilized society. He believed the conflict between the id’s wishes and the superego’s social rules produces anxiety. However, Freud believed the ego has an arsenal of unconscious defense mechanisms that help get rid of this anxious tension by distorting reality. You have probably heard of several of these. We’ll consider seven: 1. Repression banishes anxiety-arousing thoughts, feelings, and memories from consciousness. Freud believed repression was the basis for all these anxiety-reducing defense mechanisms. The aim of psychoanalysis was to 5 draw repressed, unresolved childhood conflicts back into consciousness to allow resolution and healing. 2. Regression allows an anxious person to retreat to a more comfortable, infantile stage of life. The five-year-old who wants Mom to read to him when a baby is born into the family may be regressing to a more comfortable time. 3. Through denial an anxious person refuses to admit that something unpleasant is happening. Thoughts of invincibility, such as “I won’t get hooked on cigarettes. It can’t happen to me” represent denial. The drinker who consumes a six-pack a day but claims not to have a drinking problem is another example of denial. 4. Reaction formation reverses the unacceptable impulse, making the anxious person express the opposite of the anxiety-provoking unconscious feeling. To keep the “I hate him” thoughts from entering consciousness, “I love him” becomes the feeling. If you’re interested in someone who is already going out with another, and you find yourself feeling a curious dislike instead of fondness for the unobtainable, Freud would say you’re experiencing reaction formation. 5. Projection disguises threatening feelings of guilty anxiety by attributing the problem to others. “I don’t trust him” really means, “I don’t trust myself.” Hamlet, in the Shakespearean play of the same name, thinks his mother is guilty of murder after she denies wrongdoing. “The lady doth protest too much,” The thief thinks everyone else is a thief. 6. Rationalization displaces real, anxiety-provoking explanations with more comforting justifications for one’s actions. Rationalization helps mistakes seem reasonable and often sound like excuses. The smoker insists she smokes “just to look older” or “only when I go out with friends.” After 6 addiction to cigarettes, you might hear, “It’s no big deal, I can quit whenever I want.” 7. Displacement shifts an unacceptable impulse toward a more acceptable or less threatening object or person. The classic example here is when the owner of a company gets upset and yells at the manager, who yells at the clerk, who goes home and yells at the kids, who end up kicking the dog. All except the dog could have been displacing. Personality Development What’s the Point? What were Freud’s stages of personality development? Freud’s analyses of his patients lead him to conclude that personality forms during the first five or six years of life, and that his patients’ problems seemed to originate in unresolved conflicts from the childhood years. These conflicts occurred in one of several stages that Freud called the psychosexual stages of development. Each stage is marked by the id’s pleasure seeking focus on a different part of the body (Table 25.1). The oral stage lasts through the first 18 months of life. Pleasure comes from chewing, biting, and sucking. Weaning can be a conflict in this stage. The anal stage lasts from age 18 months to 3 years. Gratification comes from bowel and bladder retention and elimination. Potty training can be a conflict in this stage. The phallic stage lasts from age 3 to 6 years. The pleasure zone shifts to the genitals. Freud believed boys felt love for their mothers and hatred, fear, and/or jealousy of their fathers. Dad is seen as a rival for Mom, and the phallic-stage boy is said to fear punishment from his father for loving his mother. Freud called this collection of feelings the Oedipus (ED-uh-pus) complex, named after the Greek 7 tragedy, where Oedipus unwittingly kills his father and marries his mother (and pokes his eyes out after realizing what he has done). Freud did not believe in a parallel process for girls, though other psychoanalysts have written about an Electra complex where girls love Dad and fear Mom. These feelings, according to Freud, are repressed as children enter a period called latency. Girls and boys, instead of fearing the same-sex parent, start to “buddy-up” to Mom or Dad. The result is girls learn to do girl-like things and boys learn boy-like behaviors. Freud called this the identification process. This offers one explanation of gender identity, which is our sense of what it means to be either male or female. The genital stage starts at puberty. At this point, and the person begins experiencing sexual feelings toward others. Freud thought that unresolved conflicts in any of the stages could cause problems later in life for adults. The person who does not work through a conflict at a given stage may become stuck or fixated in that stage. For instance, a child who has a bad experience during potty training may develop an anal fixation. This conflict may manifest itself, wrote Freud, in the adult who likes everything neat, perfect, and in its proper place. Now you know where the label “anal-retentive” comes from! Assessing the Unconscious What’s the Point? What personality assessment techniques have those from the psychodynamic perspective preferred? Before providing therapy for a personality disorder, psychologists need to assess personality characteristics. Different personality theories develop different assessment techniques. Psychoanalytic and psychodynamic therapists want assessments that reach into and reveal elements of the unconscious. True-false tests 8 are of no interest, as they would only tap into surface elements of the conscious. Instead, Freud turned to assessment techniques such as dream analysis, which he called the “royal road to the unconscious.” There are also projective tests designed to trigger projections of one’s unconscious motives. Therapists use several different kinds of projective tests. Two are particularly well known: 1) Thematic Apperception Test (TAT) In this test, subjects are shown pictures, where you can’t really tell what’s happening. The pictures are deliberately ambiguous. For instance, if you were taking a TATlike assessment, you might be shown a picture of two men in a room, one sitting looking out a window and the other standing with his back turned. After looking at the picture, you’d be asked to tell stories about it. Stories are supposed to include what is going on in the picture, as well as what was going on before and after the scene. The idea is that you would express your inner feelings and interests in the story you told. 2) Rorschach (ROAR-shock) inkblot test This is the most widely used projective test. Those administering this test assume analyzing responses to a set of ten inkblots reveals inner feelings. Subjects are asked to look at the inkblot and tell what they see. If subjects see a bat on a part of the inkblot where most people see a bat, they have given a “normal” response. But, if they see a gun where most would see a bat, they might be showing aggressiveness. Are there problems with tests like the Rorschach? Yes. Different therapists interpret the same inkblot responses in different ways, which means the test is not very reliable. No single, universally-accepted scoring system has been developed. Further, the Rorschach is not the emotional x-ray some hoped it would be. The 9 scientific community agrees that the Rorschach does not accurately predict personality characteristics (Sechrest & others, 1998). Some clinicians use the Rorschach to break the ice of a therapy session; others use it as part of a series of personality tests looking for trends among the results. But critics maintain there is “no scientific basis for justifying the use of the Rorschach scales in psychological assessments” (Hunsley & Bailey, 1999). Neo-Freudians What’s the Point? How did Freud’s key followers modify his psychoanalytic approach? Sigmund Freud attracted many followers. Several of these neo-Freudians broke from Freud in order to modify his stance on personality. Three of these pioneering psychoanalysts are Alfred Adler, Carl Jung, and Karen Horney (HORN-eye). Alfred Adler (1870-1937) Like all of the neo-Freudians, Alfred Adler agreed and disagreed with some of Freud’s views. Adler agreed on the importance of childhood experiences, but he thought social tensions, not sexual tensions, were crucial in the development of personality. Adler saw psychological problems in personalities centering on feelings of inferiority, and believed that if we start to organize our thoughts based on perceived shortcomings or mistakes, we might develop an inferiority complex. There is the origin of another famous label you’ve probably already heard.. Carl Jung (1875-1961) Unlike Adler, Carl Jung (pronounced, Yoong) discounted social factors but placed importance on the role of the unconscious in personality development. But Jung kicked it up a notch, saying we not only have an individual unconscious, but that we as a species also have a collective unconscious. This is a shared, inherited reservoir of memory traces from our species’ history. Jung thought the collective 10 unconscious included hard-wired information from birth on things we all know. According to Jung, archetypes (AR-kuh-types) or universal symbols found in stories, myths, and art, reflect this collective unconscious. For instance, the shadow archetype is the darker, evil side of human nature. Supposedly, we hide this archetype from the world and ourselves. Psychologists today reject the notion of inherited memory. However, many believe that our shared evolutionary history has contributed to some universal behavior tendencies (like hiding our worst secrets from others) or dispositions (evil). Karen Horney (1885-1952) Trained as a psychoanalyst, Karen Horney (HORN-eye) broke from Freud in several ways. She deftly pointed out that Freud’s theory was male dominated, and that his explanation of female development was inadequate. She also stated that cultural variables were the foundation of personality development, not biological variables. She felt that cultural expectations created the psychological differences between males and females, not anatomy. Basic anxiety, wrote Horney, is the helplessness and isolation felt in a potentially hostile world brought on by the competitiveness of today’s culture (Horney, 1950). Evaluating the Psychodynamic Perspective What’s the Point? How do Freud’s ideas hold up in light of modern research? No discussion of Freud’s work is complete without at least a simple update and critique. Indeed, most contemporary psychodynamic theorists do not believe Freud’s assertion that sex is the basis of personality (Westen, 1996). Nor do they classify patients as oral or anal. They do agree with Freud, that much of our mental life is unconscious; that we struggle with inner conflicts among values, wishes and fears; and that childhood experiences shape our personalities. 11 Freud’s personality theory was comprehensive, unlike any personality theory before. It influenced psychology, literature, religion, and even medicine. Still, we need to be aware of some of the weaknesses of this perspective: • Freud’s work was based on individual case studies of mostly upper class, Austrian, white women. Are experiences of these women from 100 years ago applicable to a population of say, today’s middle-class Japanese men? Were the results even applicable to the vast majority of Austrian women outside Freud’s study 100 years ago? Probably not. • Boys’ gender identity does not result from an Oedipus complex around the time of kindergarten. Gender identity is achieved even without a same-sex parent around the house (Frieze & others, 1978). • The neural network of children under three is insufficiently developed to sustain the kind of emotional trauma Freud described. • Freud underestimated peer influence on personality development, and overestimated parental influence. • Development is a lifelong process, and is not simply fixed in childhood. • Freud’s personal biases are evident in his focus on male development. • Freud’s theory is not scientific. It’s difficult to submit concepts such as the Oedipal complex or the id to the rigors of scientific testing. • Freud asked his patients leading questions which may have led to false recall of events that never really happened (Powell & Boer, 1994). These same concerns exist today over reported “repressed memories” of childhood sexual abuse. Evidence suggests therapists may actually implant false memories of abuse in the way they ask subjects questions (Ofshe & Watters, 1994). 12 Freud left a lasting legacy. Our language is laden with psychoanalytic concepts from repression to inferiority complex. Many people still believe that behaviors disguise motives, and that childhood experiences shape personality. Freud’s ideas have steadily declined in importance in the academic world for years, but some therapists, talk shows, and the public still love the concepts (Seligman, 1994). Humanistic Perspective What’s the Point? Describe the humanistic perspective. In contrast to Freud’s focus on troubled people, humanistic psychology has focused on fulfilled individuals with the goal of helping all of us reach our potential. This movement began gaining credibility and momentum in the United States in the 1960s. Humanistic psychologists wanted a psychology that: 1. emphasized conscious experience 2. focused on free will and creative abilities 3. studied all factors (not just observable behaviors) relevant to the human condition (Schultz & Schultz, 1996) Humanistic psychologists thought psychology was ignoring human strengths and virtues. Freud studied the motives of “sick” people, those who came to him with psychological problems. Humanists, such as Abraham Maslow and Carl Rogers, thought we should also study “healthy” people. They believed human personality was shaped more by our unique capacity to determine our futures than by unconscious conflicts or past learning. Abraham Maslow and Self-Actualization 13 What’s the Point? Describe Maslow’s hierarchy of needs. Abraham Maslow is famous for his hierarchy of needs (1970). Maslow believed we could only strive for self-actualization, or the highest level on his hierarchy, if our basic needs were met first. He felt we must meet the physiological needs for food, water, and air before attempting to meet the security and safety needs of the second level. And only after meeting our needs for self-esteem could we fulfill our potential as humans and obtain self-actualization. The self-actualized person works toward a life that is challenging, productive, and meaningful. Maslow formulated his beliefs by studying psychologically healthy people, not those with a psychological disorder. Maslow studied paragons of society, like Eleanor Roosevelt and Abraham Lincoln, and found that those who live productive and rich lives are: • self-aware and self-accepting. • open and spontaneous. • loving and caring. • not paralyzed by others’ opinions. • focused on a particular task that is often seen as a mission. • involved in a few deep relationships, not many superficial ones. • likely to have been moved by personal peak experiences that surpass ordinary consciousness.. These mature adult qualities, wrote Maslow, are found in those who have “acquired enough courage to be unpopular,” have found their calling, and who have learned enough in life to be compassionate. These individuals have also outgrown any mixed feelings toward their parents and are “secretly uneasy about the cruelty, meanness, and mob spirit so often found in young people.” 14 Carl Rogers and the Person Centered Approach What’s the Point? How did Rogers believe human growth could best be fostered? Humanistic psychologist Carl Rogers agreed with Maslow that people are good and strive for self-actualization. Rogers (1980) viewed people much like a seed that flourishes when it has the right mixture of ingredients, such as water, soil, and sun. The three ingredients for proper human growth, said Rogers, are acceptance, genuineness, and empathy. Rogers believed we nurture growth in others by being accepting. This is best achieved through unconditional positive regard: an attitude of total acceptance toward another person. This is an attitude that values others even when we are aware of their faults and failings. Rogers thought that family members and close friends who express unconditional positive regard for us provide us with great relief. We can let go, confess our most troubling thoughts, and not have to explain ourselves. People who are genuine nurture growth, according to Rogers. Genuine people freely express their feelings and aren’t afraid to disclose details about themselves. Those who are empathic also nurture growth. Empathy involves sharing thoughts, and a deep understanding of another’s feelings. The key to empathy is listening to another with understanding. When the listener shows understanding, the person sharing feelings has a much easier time being open and honest. Rogers wrote, “…listening, of this very special kind, is one of the most potent forces for change that I know.” 15 Acceptance, genuineness, and empathy help build a strong relationship between the parent and child, teacher and student, or any two people. For Rogers, this notion was particularly important in the relationship between a client and a therapist. Assessing Personality and the Self What’s the Point? How do humanistic psychologists assess personality? If Rogers, Maslow, or any humanistic psychologist wanted to assess your personality, you’d probably be asked to answer questions that would evaluate your self-concept. Your self-concept includes all your thoughts and feelings about yourself, in answer to the question “Who am I?” A common technique for Rogers was to ask clients to describe themselves as they are and as they would ideally like to be. He believed that the closer the actual self is to the ideal self, the more positive the self-concept. Assessing personal growth during therapy was a matter of measuring the difference between ratings of ideal and actual self. For some humanistic psychologists, any kind of written test of personality was simply too impersonal and detached from the real human being. Assessing someone’s personality could only be done through a series of lengthy interviews and personal conversations. Only in this way could a person’s unique experiences be acceptably understood. Evaluating the Humanistic Perspective What’s the Point? What are the greatest contributions of the humanistic movement? What have been the greatest weaknesses. 16 Carl Rogers once said, “Humanistic psychology has not had a significant impact on mainstream psychology. We are perceived as having relatively little importance” (Cunningham, 1985). Was Rogers correct? Society has benefited from humanistic psychology. Therapy practices, child-rearing techniques, and workplace management can all attest to a positive humanistic influence. On the other hand, there have been unintentional negative effects as well. Unconditional positive regard for children has been mistakenly interpreted as never offering constructive criticism to a child, or worse, never telling a child “no.” Critics have pointed out that many of the humanistic terms are vague and hard to operationally define in a way that other researchers test. For instance, the self-actualized person is supposed to be spontaneous, loving, and productive. Are these descriptions scientific or do they simply reflect Maslow’s values? Perhaps the primary concern of critics is that without operationally defined terms, assumptions are difficult if not impossible to test. Humanistic psychology may not have its intended impact on mainstream psychology, but perhaps it laid the foundation for the positive psychology movement of the past few years. More and more researchers are studying the human strengths and virtues, like courage and hope, of healthy people, not just the disorders of those who are not psychologically healthy. Without question, the humanistic perspective gave the study of personality some balance. The study of hope and humor in treating illness, and the research of ways to nurture creativity and empathy in children are wonderful legacies to the field. 17 Key Terms personality an individual’s characteristic pattern of thinking, feeling, and acting. psychoanalysis Freud’s theory of personality and therapeutic technique that attributes our thoughts and actions to unconscious motives and conflicts. psychodynamic approaches theories of personality based on modified Freudian principals, but different in that they are less likely to sight childhood conflicts as a source of personality development. free association in psychoanalysis, a method of exploring the unconscious in which the person relaxes and says whatever comes to mind, no matter how trivial or embarrassing. unconscious according to Freud, a reservoir of mostly unacceptable thoughts, wishes, feelings, and memories. According to contemporary psychologists, information processing of which we are unaware. preconscious information that is not conscious but is retrievable into conscious awareness. id contains a reservoir of unconscious, psychic energy that, according to Freud, strives to satisfy basic sexual and aggressive drives. The id operates on the pleasure principle, demanding immediate gratification. superego the part of personality that, according to Freud, represents internalized ideals and provides standards for judgment (the conscious) and for future aspirations. ego the largely conscious, “executive” part of personality that, according to Freud, mediates among the demands of the id, superego, and reality. The ego operates on the reality principle, satisfying the id’s desires in ways that will realistically bring pleasure rather than pain. defense mechanisms in psychoanalytic theory, the ego’s protective methods of reducing anxiety by unconsciously distorting reality. 18 psychosexual stages the childhood stages of development (oral, anal, phallic, latency, genital) during which, according to Freud, the id’s pleasure-seeking energies focus on distinct erogenous zones. projective tests a personality test, such as the Rorschach or TAT, that provides ambiguous stimuli designed to trigger projection of one’s inner dynamics. Thematic Apperception Test (TAT) a projective test in which people express their inner feelings and interests through the stories they make up about ambiguous scenes. Rorschach inkblot test the most widely used projective test, a set of 10 inkblots, designed by Hermann Rorschach; seeks to identify people’s inner feelings by analyzing their interpretations of the blots. inferiority complex according to Alfred Adler, a condition that comes from being unable to compensate for normal inferiority feelings collective unconscious Carl Jung’s concept of a shared, inherited reservoir of memory traces from our species’ history. humanistic psychology a system focusing on the study of conscious experience, freedom to choose, and capacity for personal growth. self-actualization according to Maslow, the ultimate psychological need that arises after basic physical and psychological needs are met and self-esteem is achieved; the motivation to fulfill one’s potential. unconditional positive regard toward another person. according to Rogers, an attitude of total acceptance self-concept all our thoughts and feelings about ourselves, in answer to the question, “Who am I?” Key People Sigmund Freud (1856-1939)—founder of psychoanalysis. 19 Alfred Adler (1870-1937)—neofreudian who thought social tension was more important to study than sexual tensions. Carl Jung (1875-1961)—neofreudian who thought humans shared a collective unconscious. Karen Horney (1885-1952)—neofreudian who found psychoanalysis negatively biased toward women, and believed cultural variables were the foundation of personality development. Abraham Maslow (1908-1970)—prime mover of humanistic psychology Carl Rogers (1902-1987)—humanistic psychologist who developed the clientcentered therapy approach References Cunningham, S. (1985, May). Humanists celebrate gains, goals. APA Monitor, pp. 16, 18. Frieze, I. H., Parsons, J. E., Johnson, P. B., Ruble, D. N., & Zellman, G. L. (1978). Women and sex roles: A social psychological perspective, New York: Norton. Horney, K. (1950). Neurosis and human growth: The struggle toward selfrealization. New York: Norton. Hunsley, J., & Bailey, J. M. (1999). The clinical utility of the Rorschach: Unfulfilled promises and an uncertain future. Psychological Assessment, 11(3), 266-277. Maslow, A. H. (1970). Motivation and personality (2nd ed.). New York: Harper & Row. Ofshe, R. J., & Watters, E. (1994). Making monsters: False memory, psychotherapy, and sexual hysteria. New York: Scribners. Powell, R. A., & Boer, D. P. (1994). Did Freud mislead patients to confabulate memories of abuse? Psychological Reports, 74, 1283-1298. 20 Rogers, C. R. (1980). A way of being. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. Sechrest, L., Stickle, T. R., & Stewart, M. (1998). The role of assessment in clinical psychology. In A. Bellack, M. Herson (Series eds.), & C. R. Reynolds (Vol. Ed.), Comprehensive clinical psychology: Vol. 4 Assessment. New York: Pergamon. Seligman, M. E. P. (1994). What you can change and what you can’t. New York: Knopf. Schultz, D., & Schultz, S. (1996) A history of modern psychology (6thrd ed.). Fort Worth: Harcourt Brace & Company. Westen, D. (1996). Is Freud really dead? Teaching psychodynamic theory to introductory psychology. Presentation to the Annual Institute on the Teaching of Psychology, St. Petersburg Beach, Florida. 21