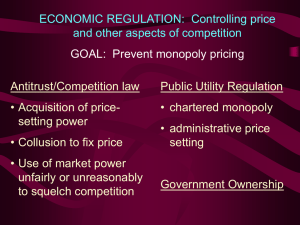

Designing Regulation for 21st Century markets

advertisement