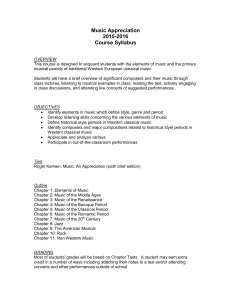

Communing with the Dead Guys

advertisement