the canterbury tales - Bowling Green City Schools

advertisement

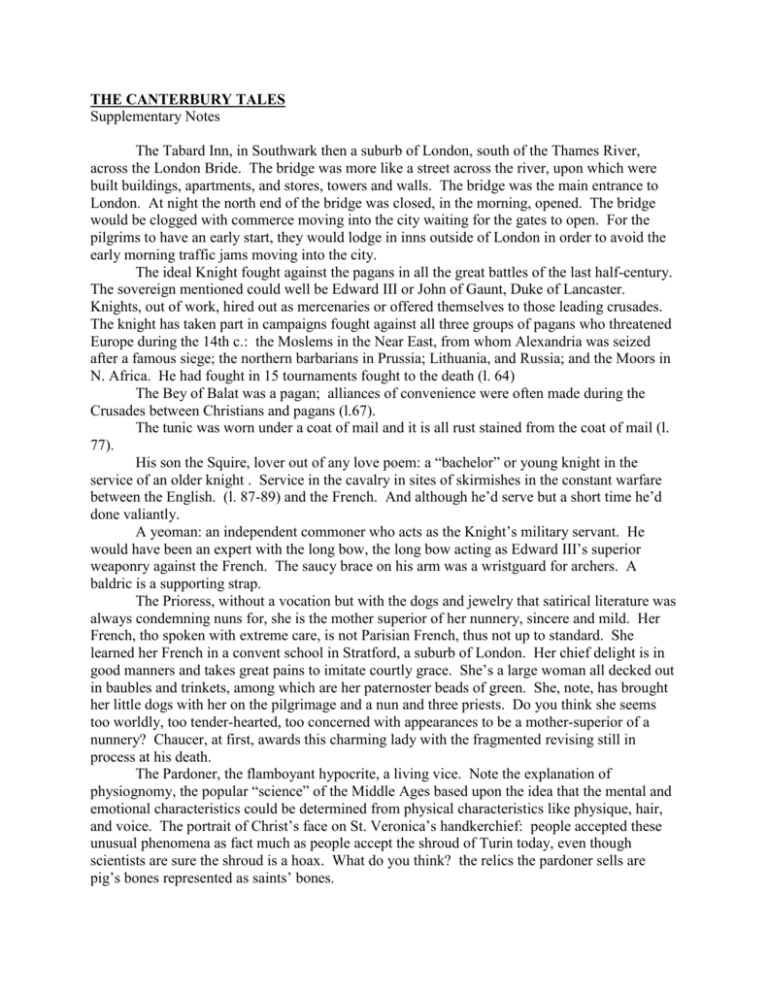

THE CANTERBURY TALES Supplementary Notes The Tabard Inn, in Southwark then a suburb of London, south of the Thames River, across the London Bride. The bridge was more like a street across the river, upon which were built buildings, apartments, and stores, towers and walls. The bridge was the main entrance to London. At night the north end of the bridge was closed, in the morning, opened. The bridge would be clogged with commerce moving into the city waiting for the gates to open. For the pilgrims to have an early start, they would lodge in inns outside of London in order to avoid the early morning traffic jams moving into the city. The ideal Knight fought against the pagans in all the great battles of the last half-century. The sovereign mentioned could well be Edward III or John of Gaunt, Duke of Lancaster. Knights, out of work, hired out as mercenaries or offered themselves to those leading crusades. The knight has taken part in campaigns fought against all three groups of pagans who threatened Europe during the 14th c.: the Moslems in the Near East, from whom Alexandria was seized after a famous siege; the northern barbarians in Prussia; Lithuania, and Russia; and the Moors in N. Africa. He had fought in 15 tournaments fought to the death (l. 64) The Bey of Balat was a pagan; alliances of convenience were often made during the Crusades between Christians and pagans (l.67). The tunic was worn under a coat of mail and it is all rust stained from the coat of mail (l. 77). His son the Squire, lover out of any love poem: a “bachelor” or young knight in the service of an older knight . Service in the cavalry in sites of skirmishes in the constant warfare between the English. (l. 87-89) and the French. And although he’d serve but a short time he’d done valiantly. A yeoman: an independent commoner who acts as the Knight’s military servant. He would have been an expert with the long bow, the long bow acting as Edward III’s superior weaponry against the French. The saucy brace on his arm was a wristguard for archers. A baldric is a supporting strap. The Prioress, without a vocation but with the dogs and jewelry that satirical literature was always condemning nuns for, she is the mother superior of her nunnery, sincere and mild. Her French, tho spoken with extreme care, is not Parisian French, thus not up to standard. She learned her French in a convent school in Stratford, a suburb of London. Her chief delight is in good manners and takes great pains to imitate courtly grace. She’s a large woman all decked out in baubles and trinkets, among which are her paternoster beads of green. She, note, has brought her little dogs with her on the pilgrimage and a nun and three priests. Do you think she seems too worldly, too tender-hearted, too concerned with appearances to be a mother-superior of a nunnery? Chaucer, at first, awards this charming lady with the fragmented revising still in process at his death. The Pardoner, the flamboyant hypocrite, a living vice. Note the explanation of physiognomy, the popular “science” of the Middle Ages based upon the idea that the mental and emotional characteristics could be determined from physical characteristics like physique, hair, and voice. The portrait of Christ’s face on St. Veronica’s handkerchief: people accepted these unusual phenomena as fact much as people accept the shroud of Turin today, even though scientists are sure the shroud is a hoax. What do you think? the relics the pardoner sells are pig’s bones represented as saints’ bones. Two taverns are mentioned in the prologue: the Tabard, and the Bell. The host is the landlord of the Tabard Inn. He becomes the 30th person on the pilgrimage, proposing that each pilgrim tell two tales going, two returning. They will all buy supper for the man who tells the best tale—a good business deal for the host. . .don’t you think? He’ll be the judge and referee, and those who don’t play will have to pay for the expenses along the way, no matter how much the journey costs. Then they draw lots to see who will start. THE WIFE OF BATH’S PROLOGUE AND TALE The wife of Bath confuses all her scripture. You may detect the incongruity of her scriptural allusions and see the true humor in them. Your text takes liberties in the translation that save you from having to match all her allusions with their true origin, but also rob the text of its depth of humor. The only scriptural references remaining in our text are Ephesians 5 and Matthew xix.21 (not footnoted) and Timothy I.ii.9 and Proverbs xxx, 21-23 (footnoted). She lists her tactics for keeping the upper hand over her husbands, the first three she outsmarted by accusing them of things they never thought of doing (l. 248-250), the fourth she tormented by flirting with other men until “he flinched. . .when the shoe pinched” (l. 308-309). the fifth, her worst husband, although he beat her, she loved him best because he was so disdainful of her. “Cheap goods have little value.” She married him for love, not wealth. She met him while her husband was away one spring and dallied with him in the meadows through the grass, setting the stage with Johnny in case her fourth should die. She, forty, Johnny, twenty, married before the month was gone once her husband was buried. She gave Johnny all her lands, her money, all her inheritance she loved him so much, which she later regretted; doing so sapped her of all her power and her freedom. As husband Johnny instructs her from books about all of the evil of womankind—Eve, Samson’s Delia, Hercules’ Dejanira, etc.—until she can take no more and rips out the pages. He strikes her; she strikes him; they fight until he, thinking her dead, remorsefully promises never to strike her again. They make up, and he turns the governance of their property back to her. (l. 455 ff) The actual text contains a list of fascinating allusions to women who betrayed or murdered their husbands: Dejanira unwittingly gave Hercules a poisoned shirt which hurt him so much that he committed suicide by fire; Pasiphae fell in love with a bull; Clymenestra, with her lover Aegisthus, slew her husband Agamemnon; Amphiaraus, betrayed by his wife Eriphyle, was forced to go to the war against Thebes; Livia murdered her husband, the poet Lucretius with a potion designed to keep him faithful.