Twelve tables - Fetial Priests - Struggle of Orders

advertisement

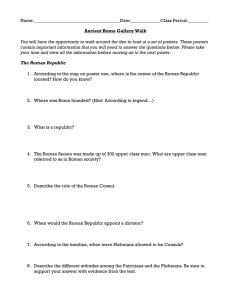

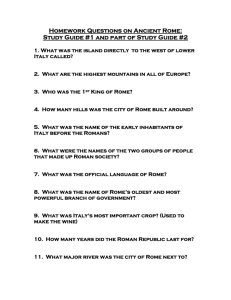

Twelve tables - Fetial Priests - Struggle of Orders - Cursus Honorum 12 Tables - 50, 490 About the Twelve Tables A century or so after the conversion of Rome from Monarchy to Republic the decemvirs issued the “Law of the Twelve Tables”. Rome was taking shape and there was a popular consent to limit the consuls’ power and write down Rome’s laws, thereby making them public for the first time. A commission of ten men named decemvirs was organized. They were granted ultimate authority over Rome for one year. By year’s end they were to produce a body of laws for the governance of the Republic. The result was the “Law of the Twelve Tables” and this body of law was to serve as the foundational Roman text in law for centuries. A second decemvirs was organized but is reported to have been more tyranical than the it’s predecessor. A common story told about the second decemvirs is one regarding Appius Claudius. He longed for Verginia and her father killed her to prevent Claudius from having her. Whether the tale is true or not resisstance to the second commision resulted in the fall of the second decemvirs. Some of their measures were moderated while some of their provisions endured. The textbook calls the Twelve Tables ‘a collection of specific, detailed, and narrowly focused provisions. They reflect a Roman society where the family and home are the primary social unit and where animal rearing and agriculture are the main economic activities. Among the things addressed in the Laws were issues of marriage and divorce, inheritance, and the rights of a father over members of his household. It also tried to regulate disputes over land ownership, property such as buildings and animals, trees and slaves and injury to person or property. It was upto the accuser to inform the defendant of the charge as well as guarantee his appearance in court. If a defendant failed to appear the law permitted the accuser to seize the defendant and transport him by force. Issues of debt were the laws’ main concerns. Debtors had thirty days to pay a debt in default or to satisfy a judgement against them. If they did not pay up in time then the creditor could seize debtor. At this point the creditor would bring the debtor to the Forum on three successive market days. If debts remain unpaid the creditor could sell the man into slavery “abroad, across the Tiber”. This phrase “abroad, across the Tiber” seem to indicate that Romans could not legally be held as slaves in Rome itself or in Latium. A debtor could enter into nexum (debt-bondage) and in becoming a nexi (a man in debt-bondage) would serve their creditor for as long as the debt remained unpaid. Struggle of Orders - pp. 53 - 57, 489 In the fifth and early fourth centuries Rome was engaged in foreign wars. At home there was a seemingly greater conflict taking place amongst groups of citizens. This conflict is called “Struggle of the Orders”. Generally it is taken to mean the conflict between two Roman classes; Patricians and Plebeians, and it is a safe interpretation. It also refers to a time in Rome when there was much disputation and fighting amongst Latin citizens in general. This struggle was the birth pains of a Republic. There was great competition between members of the Roman elite for leadership in the city which lead to frequent violence and disorder. As was common in the archaic Italian and Greek worlds leading families would try to monopolize offices when a King or great leader fell. The main issues of contention between what we can call the Patricians (aristocracy) and the Plebeians (average citizens) were access to magistracies, the ability of offials to punish at will, the roles of magistrates and citizen assemblies regarding the selection of officeholders and the forming of laws restricting the actions of magistrates. Patricians - to be a Patrician one had to belong to one of a very few families. Their origins may be in the families of the 8th century that arose to organize and lead certain Latin communities. With few exceptions Patricians were the sole holders of public office. They also administered religious life to a great extent. In taking office a magistrate would take the auspices (auspicium; rites by which an officeholder sought the approval of the gods to take up his office and the divine consent for all of his official actions). Plebeians - Plebeians greatly outnumbered the Patricians. It was not a group as homogenous as the Patricians. It contained people with a range of statuses and roles in Rome. Most were poor but not all. By the early 4th century they were producing leaders from their own ranks. Matters of land distribution and debt would have concerned them the most. They would sometimes perform a ‘secession’. It was a king of strike in a time of war. Plebeian members of an army withdrew to hills outside of Rome, choosing a leader, they refused to cooperate with the magistrates until their grievances were heard. This was successful at least 3 times. As the Plebeians grew in stature and rank a dual organization within Rome arose. The Consuls and military tribunes of Rome lead the populus Romanus in matters of politics, military and religion. Under this leadership the Plebeians created a somewhat parallel organization of officials and cults. It only concerned the Plebs and did not effect the greater populace. The first great gain for the Plebs was the tribuni plebis. They chose their own leaders. They established a cult site at the temple of Ceres, the goddess of grain, on Aventine hill. The main function of Plebeian officials was to protect their people from injustice as well as Auxilium; the giving of aid. I am unable to find the text on Cursus Homorum or on Fetial Priests. I don’t want to go from memory and miss some points. I’m including another author’s explanation. Sorry! Cursus Honorum ~ the senate ~ Cursus honorum: the 'sequence of offices' in the career of a Roman politician. The cursus honorumwas the sequential order of public offices held by aspiring politicians in both the Roman Republic and the early Empire. It was designed for men of senatorial rank. The cursus honorum comprised a mixture of military and political administration posts. Each office had a minimum age for election. There were minimum intervals between holding successive offices and laws forbade repeating an office No one could be chosen praetor until he had been quaestor, or consul until he had been praetor. These three magistracies, then, formed a career of office--the so-called cursus honorum--which it was the aim of every ambitious Roman to complete as soon as possible. To be elected quaestor a man had to be at least 30 years old [in the time of the Gracchi the age was 27], and the lowest legal ages for the praetorship and the consulship were 40 and 43 respectively. The consulship could in no case be held until three years after the praetorship. Consuls and praetors were curule magistrates, but this was not the case with the quaestor. The office of curule aedile was often held between the quaestorship and the praetorship, but it was not a necessary grade in the cursus honorum. The minimum age for this office was the twenty-seventh year Cursus Honorum • Quaestor-The first office which had to be held in a political career. Each year 20 men were elected to serve as Quaestors, i.e. secretary/treasurers. • Aedile-Each year four men were elected to serve as Aediles, i.e. managers of public buildings, services and entertainments. While this was not a required office in the Cursus Honorum, it was one which allowed a young politician to become popular with the people by spending his own money to make urban improvements. • Praetor-The second office which had to be held In a political career. Each year eight men were elected to serve as Praetors, i.e. judges. • Consul-The third and highest office of the Cursus Honorum. Each year two men were elected to serve as Consuls. I.e. Heads of State. • Censor -Although the office of Censor was frequently a logical next step for a Magistrate who had served as Consul, It was not limited to Patricians who had completed the Cursus Honorum. Every live years two men were elected to serve as Censors, i.e. Census Takers and Guardians of the Public Mores (highly regarded virtues and personal codes of behavior). The term of office for a Censor was 18 months, and after 339 B.C. It was required by law that one of the Censors be elected from the ranks of the Plebeians Fetial Priests Fetial priests were considered to be the guardians of peace. They were the ancient equivalent of Rome's first foreign diplomatic corps. The true beginnings of the order are lost in the sands of time. Creation of the order has been attributed both to Numa Pompilius (Plutarch) and to Ancus Marcius (Livy). Duties The Fetials used ritual to attempt to resolve disputes between Rome and her neighbouring cities. This ritual may have been put into place to prevent cross-border raids and reprisals between small groups or families from turning into large scale wars. Other cities in the area had similar orders of priests with the same responsibilities. It's not possible to say that the Romans were the originators of the idea. It was likely taken, like so many of the institutions of early Rome, from the Etruscans. The Fetials mediated disputes. No violent action could take place until they had declared that a negotiated settlement was impossible. The idea was to curb the Roman taste for war or to give the declaration of war its own ritual. The ritual was as follows. When a city offended Rome's honour in some way, a Fetial priest was sent to that city as a herald of the people of Rome. Once he arrived in the city, he would inform the ruling officials both of the greivance and a list of Rome's demands to resolved these grievances. also acted as heralds to neighbouring cities that had given offense to Rome, delivering the terms that would appease the Romans. He would then wait for thirty-three days for the city government to accept or reject the terms. . If the terms were accepted, the Fetials returned to Rome and peace was maintained. If the terms were rejected, the Fetials returned to Rome and consulted with the king and the Senate (later the Senate and the People). The consultation took the form of a ritual question and answer. The comitia centuriata then voted on whether or not to declare war. If war was declared, the same Fetial returned to the border of enemy territory with an escourt. He carried a spear to the border, made a ritual speech declaring war and then threw the spear into enemy territory. The Fetials themselves could not be involved in the war. The Roman army could not leave to attack the neighbouring city until the Fetials had returned to Rome after delivering the spear. The order survived in name, if not in duty, at least until the beginning of the Principate. Augustus was named a Fetial priest.