The battle against fast food begins in the home

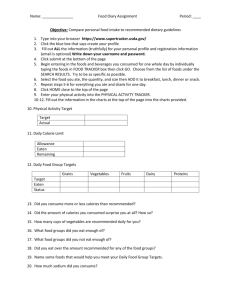

advertisement