Topic 7: Working Capital Management

advertisement

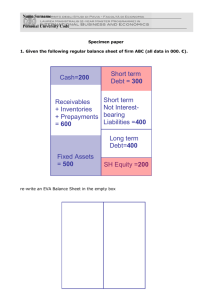

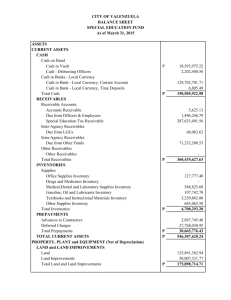

Topic 8: Working Capital Management (WCM) – Current Assets Sections: I. WCM Tasks II. The Cash Conversion Cycle III. Cash Management IV. Short-Term Investments Management V. Receivables Management VI. Inventory Management I. WCM Tasks WCM is a tactical task. Academia and practitioners usually pay more attentions to strategic tasks, such as capital budgeting and capital structure. Sound WCM usually means minimizing the use of current assets for operations (think: lean). The benefits include (1) cost reduction because of lower working capital, and (2) higher operating efficiency because of higher turnover. WCM involves two basic questions: (1) What is the appropriate amount of current assets, and (2) how should these assets be financed? In general, we use the following definitions: Working capital: current assets used in operations; Net working capital (NWC): current assets minus current liabilities. However, practitioners frequently use these terms to mean different thing. For example, the concept of “zero working capital” involves a movement minimizing working capital that is defined as inventories + receivables – payables. Here, the first two items are needed to make sales and the final item can be used to finance inventories. The concept of zero working capital, to some degree, was inspired by the concept of justin-time. The same logic behind the two concepts is to eliminate waist (poorly used or unused assets). The ability of the firm to adopt these concepts largely hinges on the firm’s market power and its business nature. For instance, Toyota is a powerful firm and it can maintain a very low inventory because it forces its suppliers to store the inventory in their warehouses. In addition, some firms simply need to invest a lot in inventories and receivables so that they can grow or keep their businesses in the long run. -----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------Minicase #8-1: The textbook uses Campbell Soup as an example (p.268): “To illustrate the benefits of striving for zero working capital, in just one year [I believe it was 1998] Campbell Soup pared its working capital by $80 million. It used the cash to develop new products and to buy companies…Equally important, the company expects to increase profits by $50 million over the next few years by lowing overtime labor and storage costs.” The ratio of (receivables + inventories – payables) /sales are 11.46% (1992), 12.21% (1993), 11.75% (1994), 10.37% (1995), 9.62% (1996), 9.57% (1997), 8.42% (1998), 9.57% (1999), 9.11% (2000), 8.96% (2001), 10.40% (2002), 10.62% (2003), and 11.18% (2004). Tasks: What do you observe? -----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------Net operating working capital (NOWC): operating current assets – operating current liabilities. In general, NOWC = cash + accounts receivable + inventories – accounts payable – accruals. II. The Cash Conversion Cycle The concept of zero working capital can be better understood by being familiar with the concept of the cash conversion cycle (CCC). The CCC is the cycle that a firm purchase inventory, sell goods (on credit), and then collect accounts receivable. Sound working capital policy is to seek an optimal tradeoff between minimizing the CCC (benefits) and the potential loss of sales (cost #1) because of potentially tighter policies on inventory and receivables and higher COGS (cost #2) because of longer payables deferral period. Holding other factors constant, minimizing the CCC reduces the amount of cash tied in operations. This (1) reduces the costs of using cash, and (2) increases free cash flow. The CCC model in Figure 20-1, p. 227 is characterized by the following identity: Inventory conversion period + receivables collection period = payables deferral period + CCC So, the idea is that reducing the CCC amounts to (1) decrease inventory conversion cycle, (2) decrease receivables collection period, (3) increase payables deferral period, or a combination of the above. Inventory conversion cycle: the average time required to convert materials into finished goods and then to sell those goods = inventory/sales per day. Receivables collection period: the average time required to convert the firm’s receivables into cash = receivables/sales per day Payables deferral period: the average time between the purchase of materials and labor and the payment of cash for them = payables/COGS per day Campbell Soup’s financial statements are retrieved from the company’s website: Financial Summary Five-Year Review - Consolidated (millions, except per share amounts) Fiscal Year Summary of Operations Net sales 2004 $ 7,109 Earnings before interest and taxes Earnings before taxes Earnings before cumulative effect of accounting change Cumulative effect of accounting change Net earnings Financial Position Plant assets - net Per Share Data Earnings before cumulative effect of accounting change - basic Number of shareowners (in thousands) Weighted average shares outstanding Weighted average shares outstanding - assuming dilution 2002 $ 6,133 20 $ 5,771 1,115 947 1,105 924 984 798 1,1 9 647 626 525 6 647 (31) 595 525 6 $ 1,843 6,675 3,353 874 $ 1.58 Earnings before cumulative effect of accounting change - assuming dilution Net earnings - basic Net earnings - assuming dilution Dividends declared Other Statistics Capital expenditures $ 6,678 $ 1,901 Total assets Total debt Shareowners' equity (deficit) 2003 $ 1,684 6,205 3,528 387 $ 1.52 1.57 1.58 1.57 0.63 $ 288 $ 1,637 5,721 3,645 (114) $ 1.28 1.52 1.45 1.45 0.63 $ 283 5,9 4,0 (24 $ 1.57 1.28 1.28 1.28 0.63 $ 269 1 1 1 0 $ 200 45 409 46 411 47 410 4 412 411 411 4 Balance Sheet (millions, except per share amounts) Current Assets Cash and cash equivalents Accounts receivable (Note 11) Inventories (Note 12) Other current assets (Note 13) August 1, 2004 August 3, 20 $ $ 32 490 795 164 Total current assets 1,481 1 Plant Assets, Net of Depreciation (Note 14) Goodwill (Note 3) Other Intangible Assets, Net of Amortization (Note 3) Other Assets (Note 15) 1,901 1,900 1,095 298 1 1 1 Total assets Current Liabilities Notes payable (Note 16) Payable to suppliers and others Accrued liabilities Dividend payable Accrued income taxes $ 6,675 $ 6 $ 810 607 607 65 250 $ 1 Total current liabilities 2,339 2 Long-term Debt (Note 16) Nonpension Postretirement Benefits (Note 9) Other Liabilities (Note 17) 2,543 298 621 2 Total liabilities 5,801 5 Shareowners' Equity (Note 19) Preferred stock; authorized 40 shares; none issued Capital stock, $.0375 par value; authorized 560 shares; issued 542 shares Additional paid-in capital Earnings retained in the business Capital stock in treasury, 134 shares in 2004 and 132 shares in 2003, at cost Accumulated other comprehensive loss - Total shareowners' equity Total liabilities and shareowners' equity 20 264 5,642 5 (4,848) (204) (4 ( 874 $ 6,675 $ 6 For fiscal year 2004, inventory conversion cycle = inventory/sales per day = 795/(7109/365) = 40.82 days. Receivables collection period = receivables/sales per day = 490/(7109/365) = 25.16 days. Payables collection period: the average time between the purchase of materials and labor and the payment of cash for them = payables/COGS per day = 607/(4187/365) = 52.92 days. The CCC = 40.82 + 25.16 – 52.92 = 13.06 days. On average, a dollar is tied up in current assets for 13.06 days. Suppose that Campbell Soup spends an average of $10 million per day on materials and labor. This operation is financed internally for 13.06 days. So the firm’s working capital financing needs will be $130.6 million. If the firm is able to reduce the CCC from 13.06 days to 5.06 days, the firm will have $80 million for other investments and uses. -----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------Question: Is the CCC always positive? If not, what does this mean? -----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------III. Cash Management Cash is often called a “non-earning asset.” The goal of cash management is to minimize the amount of cash the firm must hold and at the same time to have sufficient cash to (1) to meet expected cash needs, (2) to take trade discounts, (3) to maintain its credit rating, and (4) to meet unexpected cash needs. An average industrial firm holds about 1.5% of its assets in cash. The usual cash management techniques include: (1) Cash flow synchronization: time cash receipts to coincide with cash requirements so that cash balances needed to support operations can be reduced. (2) Speed up the incoming check-clearing process (so that the firm gets the money asap). For this reason, some firms set up regional offices or regional lockboxes, e.g., P.O. boxes, for receiving checks. (3) Slowing down the outgoing check-clearing process (so that the firm pays the money as slow as possible). (4) Speeding up receipts. For example, payment by wire of automatic debit is encouraged (Sam’s). IV. Short-Term Investment Management Short-term investments are quasi-cash. A firm holds short-term investments mainly for liquidity purpose. The return from short-term investments is usually much lower than the return from the firm’s operating assets. Consequently, a consistent, large amount of short-term investments is an indicator of poor use of cash. V. Receivables Management Receivables are costly; firms would prefer to sell for cash than on credit. However, buyers expect trade credit. In short, sales = f(credit policy, …..). An example of credit term is “2/10, net 30.” This means that buyers need to pay the full amount in 30 days. If the buyer pays in 10 days, there is a 2% discount. There are two additional aspects of credit policy: (1) Credit standard: the required financial strength of acceptable credit customers (e.g., bank loans). High standard = lower sales = lower bad debts. (2) Collection policy: the toughness in attempting to collect on slow-paying accounts. If you are too tough on the “net 30” term, some of your customers may walk away and buy from your competitors in the future. Think: credit policy is part of your product that you sell (the fries in your lunch combo: hamburger + fries; you may buy the combo because you like the fries). The credit manager should constantly monitor two things, (1) days sales outstanding (DSO) and (2) the aging schedule, to control the quality of receivables. DSO is also called the average collection period (ACP). Suppose that 60% of sales are on credit: 50% paid on Day 30 and 10% paid on Day 10. 40% of sales are cash transactions. DSO = ACP = 50% × 30 + 10% × 10 + 40% × 0 = 16 days. Usually, you’d like to see this number to be slightly smaller than the industry average. If this number is too low, the firm might loss sales. An aging schedule breaks down a firm’s receivables by age of account. For example, an aging schedule might look like this: Age of Account (Days) 0-10 11-30 31-45 Value of Account $1,215,122 $520,766 0 Percentage 70% 30% 0 46-60 Over 60 Total Receivables 0 0 $1,735,888 0 0 100% If the schedule begins to show an increasing percentage of past-due accounts, the firm’s credit policy and implementations may need to be tightened. VI. Inventory Management Inventory management techniques are taught in your POM course. Those techniques are to seek a tradeoff between two goals: (1) enough inventories to meet sales, (2) lowest possible inventories to reduce inventory costs. Example: When a firm does not have enough inventories: Sony did not have enough Plasma TV to meet demands in 2004.