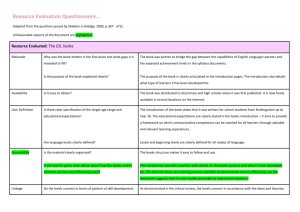

centre for english teacher training

advertisement