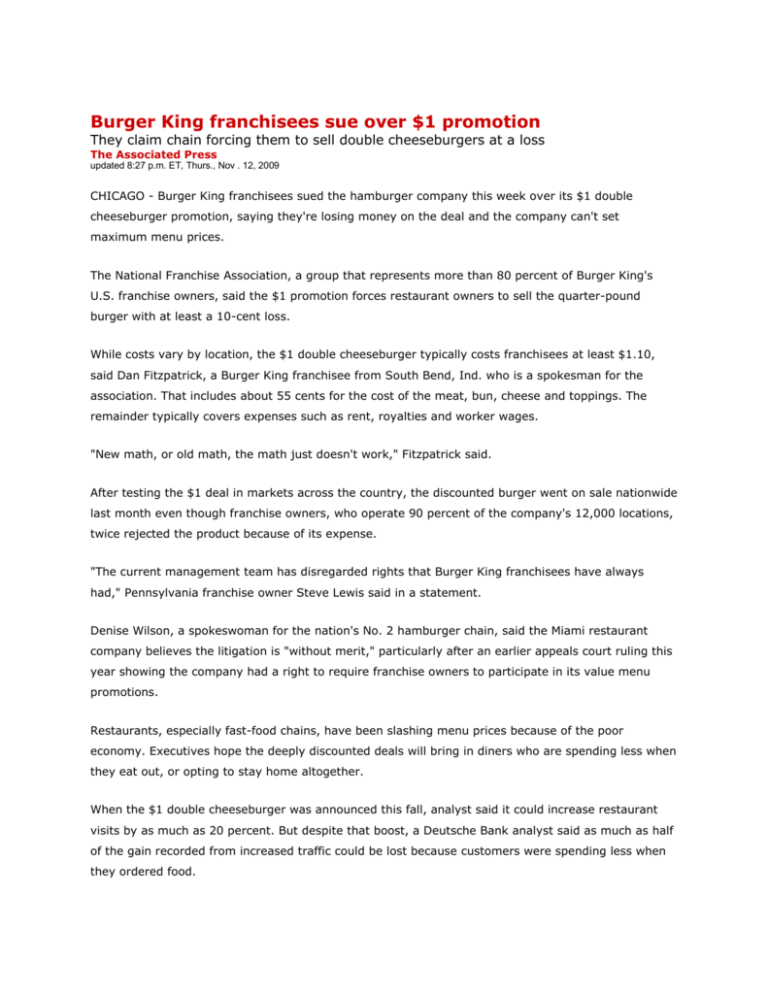

Burger King franchisees sue over $1 promotion

They claim chain forcing them to sell double cheeseburgers at a loss

The Associated Press

updated 8:27 p.m. ET, Thurs., Nov . 12, 2009

CHICAGO - Burger King franchisees sued the hamburger company this week over its $1 double

cheeseburger promotion, saying they're losing money on the deal and the company can't set

maximum menu prices.

The National Franchise Association, a group that represents more than 80 percent of Burger King's

U.S. franchise owners, said the $1 promotion forces restaurant owners to sell the quarter-pound

burger with at least a 10-cent loss.

While costs vary by location, the $1 double cheeseburger typically costs franchisees at least $1.10,

said Dan Fitzpatrick, a Burger King franchisee from South Bend, Ind. who is a spokesman for the

association. That includes about 55 cents for the cost of the meat, bun, cheese and toppings. The

remainder typically covers expenses such as rent, royalties and worker wages.

"New math, or old math, the math just doesn't work," Fitzpatrick said.

After testing the $1 deal in markets across the country, the discounted burger went on sale nationwide

last month even though franchise owners, who operate 90 percent of the company's 12,000 locations,

twice rejected the product because of its expense.

"The current management team has disregarded rights that Burger King franchisees have always

had," Pennsylvania franchise owner Steve Lewis said in a statement.

Denise Wilson, a spokeswoman for the nation's No. 2 hamburger chain, said the Miami restaurant

company believes the litigation is "without merit," particularly after an earlier appeals court ruling this

year showing the company had a right to require franchise owners to participate in its value menu

promotions.

Restaurants, especially fast-food chains, have been slashing menu prices because of the poor

economy. Executives hope the deeply discounted deals will bring in diners who are spending less when

they eat out, or opting to stay home altogether.

When the $1 double cheeseburger was announced this fall, analyst said it could increase restaurant

visits by as much as 20 percent. But despite that boost, a Deutsche Bank analyst said as much as half

of the gain recorded from increased traffic could be lost because customers were spending less when

they ordered food.

The lawsuit was filed Tuesday in U.S. District Court in Southern Florida.

Copyright 2009 The Associated Press. All rights reserved. This material may not be published,

broadcast, rewritten or redistributed.

URL: http://www.msnbc.msn.com/id/33893367/ns/business-food_inc/

The following article can be viewed here:

http://www.qsrweb.com/article.php?id=16477

Burger King responds to franchisee suit

• 13 Nov 2009

Earlier this week, the National Franchisee Association filed a class action suit against

Burger King, as reported Thursday on QSRweb.com. The suit, filed on behalf of Burger

King operators, takes issue with Burger King's maximum pricing policy, specifically

regarding the company's decision to add the quarter-pound Double Cheeseburger to the

value menu.

Burger King issued a statement Thursday and has since revised it:

Burger King Corp. (BKC) believes the National Franchisee Association’s (NFA) lawsuit

regarding the addition of the $1 quarter-pound Double Cheeseburger to the BK Value

Menu is without merit. The $1 quarter-pound Double Cheeseburger is simply an

addition to the BK Value Menu, which has been in place since 2002.

The U.S. Court of Appeals for the Eleventh Circuit decided in June of this year that BKC

has the contractual right to require franchisee participation in its BK Value Menu

program. In fact, the Court (an appellate court immediately below the U.S. Supreme

Court), could not have been clearer when it stated "[t]here is simply no question that

BKC had the power and authority under the Franchise Agreements to impose the Value

Menu on its franchisee."

Additionally, it was and has never been BKC’s intent to dictate prices across its menu.

Other than setting a maximum price on a small group of items on the BK Value Menu,

BKC has never set price restrictions for franchisees.

BKC has been working with the NFA to try to resolve this dispute. The company is

disappointed in the NFA's decision to file a suit regarding a value promotion that is

allowing the brand to effectively compete in this difficult consumer environment by

driving traffic and profitable sales.

Do Franchisee Associations Have the Power to Block Franchisor Actions?

Cheap Burgers Hang in the Balance.

Written By: Dan Ryan on November 13, 2009 2 Comments

Interesting situation flaring up with the flame broiled king. Burger King franchisees are

revolting against the franchisor with a lawsuit over the company’s new promotion to sell $1.00

double cheeseburgers. This situation raises a few issues and provides a glimpse into how a large

franchise organization operates.

First, the legal issue in the suit is whether Burger King has a right to force its franchisees to sell

double cheeseburgers at $1.00. Franchisors must be cognizant of anti-trust laws which exist to

prevent companies from using their size and power and collusion to set artificial prices – aka

“price fixing” – in an effort to restrain trade. This includes an absolute bar against setting

minimum prices, but allows franchisors a bit of latitude in setting maximum prices for products.

The Supreme Court requires these pricing mechanisms to be evaluated with a “rule of reason”

test, and only prevents those schemes that unreasonably restrain trade. (Is it reasonable to sell

double cheeseburgers at $1.00? I can’t get the image of the kid in Fast Food Nation out of my

head: “there’s a reason they only cost 99 cents”.) This effectively gives franchisors the right to

set promotional pricing as Burger King has done here.

But even if it is legal for franchisors to set promotional pricing, is it good for the system? In

large franchise systems, franchisees often form associations – independent organizations

designed to allow collective action – to work with the franchisor on a number of issues relevant

to the franchisees. Here the National Franchisee Association of BK franchisees is pushing back

against the franchisor on the pricing promotion:

While costs vary by location, the $1 double cheeseburger typically costs franchisees at least

$1.10, said Dan Fitzpatrick, a Burger King franchisee from South Bend, Ind. who is a spokesman

for the association. That includes about 55 cents for the cost of the meat, bun, cheese and

toppings. The remainder typically covers expenses such as rent, royalties and worker wages.

After testing the $1 deal in markets across the country, the discounted burger went on sale

nationwide last month even though franchise owners, who operate 90 percent of the company’s

12,000 locations, twice rejected the product because of its expense. (emphasis added)

First of all, 55 cents for all of the ingredients in a double cheeseburger? Yup. Secondly, the

franchisees are simply arguing that they don’t want to lose money with every double

cheeseburger sold. However the courts come down on whether the lawsuit has any merit, the

bottom line is that the franchisees just want more say in what the chain requires of them, and are

using this collective action by the franchisee association to get it.

We’ll have to watch and see whether BK will respect the wishes of its franchisees to “have it

their way”, but this episode at least provides a good example of the what can happen when a

franchisor goes against the wishes of its franchisees. In the mean time, enjoy your cheap

burgers.

What do you think? Is BK being unreasonable to its franchisees?

http://blog.dryanlaw.com/2009/11/13/can-franchisee-associations-block-franchisor-actions-cheapburgers-hang-in-the-balance/

Business Law Blog

http://www.franchisetimes.com/content/story.php?article=01455

Franchisees Sue Burger King over Mandatory Pricing

http://www.zimbio.com/Franchise+Money+Maker++The+place+to+learn+about+business/articles/zQuuO3hHdgW/Franchisees+Sue+Burger+King+ove

r+Mandatory

ATLANTA – On Tuesday, the National Franchisee Association (NFA) filed its second class action

lawsuit this year against Burger King Corporation, this time for violating the terms of their franchise

agreements by purporting to mandate maximum prices for certain products. According to the

complaint filed in federal court in the Southern District of Florida, NFA is asking the court to declare

that Burger King does not have the authority to set prices for its independently owned franchises.

At the center of the dispute is the BK Double Cheese Burger (DCB) that Burger King is now

mandating franchisees to sell at “no more than the maximum price of $1.00,” which NFA states is

below franchise owners’ cost. Burger King has recently taken the position that it has a right under

the provision of “Standards of Uniformity and Operation” of its franchise agreement to make the

pricing requirement. Although in recent years, Burger King inserted an update to its operational

manual that requires “value menu” items priced at $1, franchisees allege the company’s action is

improper. They argue that the franchisor’s decision is contrary to decades of practice, and is

inconsistent with its duty of good faith and fair dealing because it is forcing owners to sell the DCB at

a loss. And they declare, on October 9, 2009, Burger King admitted in writing that the sale of the

cheeseburger product at $1 could lead to bankruptcy.

Burger King Corporation responded saying that it has been working with the NFA to try to resolve

this dispute. The company says it is disappointed in NFA’s decision to file a suit regarding a value

promotion that is allowing the brand to effectively compete in this difficult consumer environment by

driving traffic and profitable sales.

But the NFA sees it differently. “Our franchisee community is united in protecting our entrepreneurial

rights as independent business owners, but we are also disappointed that we need to take legal

action against our franchisor,” William Harloe, Jr., NFA chairman said in a press release. “The

mission statement of the NFA is to preserve the economic well being of all members. After attempts

to compromise on maximum pricing were unsuccessful, we have been forced to pursue a judicial

resolution of this issue.”

In May 2009, the NFA filed lawsuits against Burger King, Coca-Cola, and Dr Pepper on behalf of all

franchisees. That action seeks a declaratory judgment from the court that the franchisees are the

intended third-party beneficiaries under certain soft drink agreements and are entitled to receive their

franchisee restaurant operating rebates, in full, as they had since 1990.

The NFA purports to serve as the official voice of the Burger King franchisee community. The

organization consists of 19 regional franchisee associations, and represents more than 80 percent of

US franchised Burger King restaurants.

NFA Leaders Speak Out

Steve Lewis, former NFA chairman, 1998 to 2001, expressed his disappointment in the direction of

BKC’s relations with its franchisees. “As a former NFA chairman, I led ‘Project Champion,’ a

franchisee-led initiative to turn Burger King into a publicly traded company. Unfortunately, the current

management team has disregarded rights that Burger King franchisees have always had. I never

imagined that we would be forced to take these steps.”

Previous chairman Julian Josephson chimed in, “Our franchisor has declared they have the right to

set our menu board prices even though our franchise agreements do not give them this right.

Despite franchisee profitability concerns with recent price-pointed initiatives, BKC decided to move

forward and disregard franchisees’ best interests or their rights to set their own menu prices.”

Josephson served as the NFA’s head from 2001 to 2004.

Harloe also stressed that the NFA and its member franchisees prefer to resolve the franchisee

restaurant operating funds and maximum pricing lawsuits amicably, but that circumstances have left

no alternative except to pursue legal remedies to questions concerning franchise agreements.

BKC Declares It Has Contractual Right

Denise T. Wilson, BKC’s senior analyst in communications, issued this statement:

Burger King Corp. (BKC) believes the National Franchisee Association’s (NFA) lawsuit regarding the

addition of the dollar quarter Double Cheeseburger to the BK Value Menu is without merit. The dollar

quarter pound Double Cheeseburger is simply an addition to the BK Value Menu, which has been in

place since 2002.

The U.S. Court of Appeals for the Eleventh Circuit decided in June of this year that BKC has the

contractual right to require franchisee participation in its BK Value Menu program. In fact, the Court

(an appellate court immediately below the US Supreme Court), could not have been clearer when it

stated "[t]here is simply no question that BKC had the power and authority under the Franchise

Agreements to impose the Value Menu on its franchisee."

Additionally, it was and has never been BKC’s intent to dictate prices across its menu. Other than

setting a maximum price on a small group of items on the BK® Value Menu, BKC has never set

price restrictions for franchisees.

Burger King did not respond to these specific questions presented by Blue MauMau:

Do you feel this lawsuit fairly represents the position of the majority of franchisees in the BK system?

Is the $1 price of the DCB under cost to the franchisees, causing them to incur a loss on the sale of

the product?

The complaint states that BKC on October 9, 2009, admitted in writing that sale of DCBs at the price

specified by BKC could lead to bankruptcy. In what context did BKC make that statement? Why

would Burger King make such a requirement, when it could be to the detriment of franchisees?

With two class action lawsuits filed against BKC this year, how would you describe the relationship

with your franchisee community?

BURGER KING CORPORATION, Plaintiff-Counter Defendant-Appellee, versus E-Z EATING, 41

CORPORATION, E-Z EATING 47 CORPORATION, ELIZABETH SADIK, LUAN SADIK, E-Z EATING 8TH

CORP., E-Z EATING 46TH CORP., Defendants, Counter-Claimants, Appellants.

No. 08-15078

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE ELEVENTH CIRCUIT

572 F.3d 1306; 2009 U.S. App. LEXIS 14140; 21 Fla. L. Weekly Fed. C 1973

June 30, 2009, Decided

June 30, 2009, Filed

PRIOR HISTORY: [**1]

Appeal from the United States District Court for the Southern District of Florida. D. C. Docket No.

07-20181-CV-MGC.

Burger King Corp. v. E-Z Eating 8th Corp., 2008 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 9831 (S.D. Fla., Feb. 11, 2008)

DISPOSITION: AFFIRMED.

CASE SUMMARY

PROCEDURAL POSTURE: Appellant franchisees alleged appellee, a fast-food franchisor,

violated an implied covenant of good faith and fair dealing in failing to grant the franchisees

an exception to a system-wide program as to certain meals on the menu. The franchisor

argued the franchisees had not properly requested an exception. The United States District

Court for the Southern District of Florid granted the franchisor summary judgments. The

franchisees appealed.

OVERVIEW: The Franchise Agreements provided that the franchisee agreed to accept and

comply with modifications, revisions, and additions to the manual. There was simply no

question that the franchisor had the power and authority under the Franchise Agreements to

impose the new menu program on its franchisees. A principal of the franchisees admitted he

did not submit a written exception request, even though he was aware that the new program

required exceptions to be requested in writing. He testified that at first he did not submit a

written request because he assumed the entire region for his type of restaurant and

exception would not be excepted. He testified he only applied for the exception verbally,

assuming that verbally was fine, but that nobody ever told him it was. While letters from the

franchisees' attorney discussed the exception, neither letter specified which of the three

exceptions was sought, or why they qualified under a particular exception. In contrast to the

franchisees' vague evidence of a meeting in which the franchisor waived its written request

requirement, every communication in evidence from the franchisor on the topic invoked that

requirement.

OUTCOME: The summary judgments were affirmed.

LexisNexis® Headnotes Hide Headnotes

COUNSEL: For E-Z Eating, 41 Corporation, Appellant: Oliver D. Griffin, Spector Gadon & Rosen, P.C.,

PHILADELPHIA, PA.

For E-Z Eating 47 Corporation, Elizabeth Sadik, Luan Sadik, E-Z Eating 8th Corp., E-Z Eating 46th

Corp., Appellants: George M. Vinci, Jr., Spector Gadon & Rosen LLP, ST PETERSBURG, FL; Richard

Gallucci, PHILADELPHIA, PA.

For Burger King Corporation, Appellee: Michael D. Joblove, Genovese, Joblove & Battista, Miami,

FL; Martin J. Keane, Genovese Joblove & Battista, P.A., MIAMI, FL.

JUDGES: Before BARKETT and FAY, Circuit Judges, and TRAGER, * District Judge.

* Honorable David G. Trager, United States District Judge for the Eastern District of New York,

sitting by designation.

OPINION BY: FAY

OPINION

[*1307] FAY, Circuit Judge:

This litigation involved the operation of several Burger King franchise

restaurants in the New York area by Appellants Elizabeth and Luan Sadik and their corporate

entities. The parties brought multiple claims and counterclaims against each other in three

separate lawsuits. These cases were consolidated before Judge Cooke, who held numerous

hearings before issuing [*1308] two final [**2] summary judgments against Appellants.

The appeal pending here has been boiled down to one key question: whether Appellee

Burger King Corporation

("BKC") violated an implied covenant of good faith and fair dealing in failing to grant Appellants an

exception to a system-wide program known as the Value Menu. A subpart of this question is

whether or not Appellants properly requested such an exception. After reviewing the record,

studying the briefs, and hearing oral argument, we conclude that Appellants failed to create a

genuine issue as to whether they properly requested an exception to the Value Menu. We

therefore affirm the summary judgments against them.

I. FACTS

A. Background

1. The Parties and Franchise Agreements

BKC is a Florida corporation that operates a world-wide system of both company-owned

and franchised fast-food restaurants. Through various corporate entities, 1 Appellants

Elizabeth and Luan Sadik ("the Sadiks") owned and operated five of BKC's franchised

restaurants in New York City, New York. Four of the Sadiks' franchise restaurants are the

subject of this action. 2 All four restaurants were "in-line" restaurants - that is, they were not

free-standing buildings. They were [**3] as follows:

Number

Location

Date of Franchise Agreement

BK # 12287

777 8th Avenue

March 10, 1999

New York, NY

BK # 12288

55 West 46th Street

August 4, 1999

New York, NY

BK # 11100

485 5th Avenue

October 15, 1997

Number

Location

Date of Franchise Agreement

New York, NY

BK # 13447

129 East 47th Street

February 2, 2001

New York, NY

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - Footnotes - - - - - - - - - - - - - - 1 These corporate entities are: E-Z Eating 8th Corporation, E-Z Eating 41st Corporation, E-Z Eating

46th Corporation, and E-Z Eating 47th Corporation.2 As explained below, this case involves the

following three cases which were consolidated on January 30, 2008: (1) Burger King Corp.

v. E-Z Eating 8th Corp., E-Z Eating 46th Corp., Luan Sadik & Elizabeth Sadik, Case No. 07-20181; (2)

Burger King Corp.

v. E-Z Eating 41 Corp., EZ Eating 47 Corp., Luan Sadik & Elizabeth Sadik, Case No. 08-20155; and (3)

E-Z Eating 41 Corp., E-Z Eating 47 Corp., Luan Sadik & Elizabeth Sadik v. Burger King Corp

., Case No. 08-20203.

- - - - - - - - - - - - End Footnotes- - - - - - - - - - - - - -

The Sadiks entered into four identical Franchise Agreements 3 with BKC, assigned the

Agreements to corporate entities they had created for each of the restaurants, and personally

guaranteed the corporate entities' obligations. Several provisions of the Franchise

Agreements are of particular relevance here. According to [**4] Section 5(A), the

franchisee agreed to adopt and adhere to the operating procedures outlined in BKC's Manual

of Operating Data ("MOD Manual"). Further, Section 5(A) provided that the franchisee

"agrees that changes in the standards, specifications and procedures may become necessary

and desirable from time to time and agrees to accept and comply with such modifications,

revisions and additions to the MOD Manual which BKC in the good faith exercise of its

judgment believes to be desirable and reasonably necessary."

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - Footnotes - - - - - - - - - - - - - - 3 We refer to the Franchise Agreements based on the number of the restaurant to which they

pertained - for example, "the # 12287 Franchise Agreement." We also refer to the restaurants

themselves based on their numbers - for example, "BK # 12287."

- - - - - - - - - - - - End Footnotes- - - - - - - - - - - - - -

Pursuant to Section 6(I), BKC agreed to provide "[s]uch ongoing support as BKC deems

reasonably necessary to continue to communicate and advise FRANCHISEE as to the

Burger King System including [*1309] the operation of the Franchised Restaurant."

Section 18(A)(9) provided that abandonment of a franchise restaurant (defined as cessation

of operations) without BKC's consent would constitute a material act of default and good

cause for BKC to terminate [**5] the Agreement. Section 18(B) granted the franchisees a

limited license to use BKC's marks for as long as the Agreements remained valid.

2. The Assistance Agreement

After several years in business the Sadiks' restaurants became unprofitable, and the Sadiks

fell behind in their payments to BKC. As of April 18, 2005 the Sadiks had defaulted on

royalty payments, advertising fees, and other payments required under the Franchise

Agreements. The Sadiks were indebted to BKC for $ 334,779.

The Sadiks began working with a BKC financial restructuring officer and came up with a

plan to make their restaurants viable again. On June 16, 2005 the Sadiks signed a Guaranty

in which they personally guarantied to BKC each and every obligation the E-Z Eating

corporate entities assumed in the Franchise Agreements. On June 21, 2005, Appellants

entered into an Assistance Agreement in which they agreed to a payment schedule and also

executed a Promissory Note setting forth the terms on which they would pay their debts.

The Assistance Agreement included a cross-default provision. Specifically, according to

Section VII(B), the occurrence of an additional event of default under any of the Franchise

Agreements subsequent [**6] to June 21, 2005 would constitute "Event of Default" as

defined by the Assistance Agreement. According to Section VIII, the occurrence of such an

Event of Default would constitute a default under every Franchise Agreement, and would

automatically terminate each one without further notice from BKC.

3. BKC's Value Menu

On February 13, 2006 BKC sent a systemwide memorandum describing its new "Value

Menu" (the "Value Menu Memo"). The Memo explained that while BKC's general policy

was to allow franchisees to set prices for the products they sold, BKC was instituting a

special Value Menu with items to be sold at certain maximum price points established by

BKC. The Memo stated that the Value Menu was "a required menu item and, as such, must

be sold in all U.S. restaurants unless an exception is granted pursuant to this policy memo."

Further, the Memo stated, failure to comply would be considered a default under the

applicable franchise agreement.

Regarding the Value Menu "exceptions," the Memo explained that "[t]here are certain very

limited exceptions to this Policy, which BKC may grant in its sole and absolute discretion."

The Memo outlined three different exceptions: for restaurants with [**7] limited access, for

in-line restaurants, and for restaurants located in a highly seasonal tourist destination. Each

exception had its own specific criteria. The criteria for the in-line exception were: "(1) the

restaurant must be an in-line restaurant, and not a free-standing building; (2) the restaurant

must not have a drive-thru; and (3) no FFHR 4 competitor in the trade area is offering a

value menu in accordance with the competitive chain's standard national value proposition."

The Memo instructed franchisees who wished to qualify under the in-line exception to

"provide a written request to their DVP [*1310] [Division Vice- President] for an 'in-line'

exception."

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - Footnotes - - - - - - - - - - - - - - 4 Although we could not find a definition for this acronym in the briefs or the record, we believe it

refers to "fast food hamburger restaurant."

- - - - - - - - - - - - End Footnotes- - - - - - - - - - - - - -

After receiving the Memo the Sadiks did not institute the Value Menu in their four franchise

restaurants. On March 17, 2006 BKC Assistant General Counsel Stephanie Doan sent a

"Demand for Compliance" letter to the Sadiks. This Demand informed the Sadiks that if all

four of their franchise restaurants did not begin complying with the Memo and offering the

Value Menu items at the maximum [**8] price points within forty-eight hours, BKC would

declare a default in all four Franchise Agreements. The Demand stated that if the Sadiks

believed they met the requirements for an exception to the Value Menu policy, they must

submit a "written request, along with documentation" to the Division Vice-President. The

Demand further stated that the terms of the Letter itself "may be modified only by a written

modification under [Ms. Doan's] signature or the signature of another BKC attorney" and

that the Sadiks "[could not] rely on oral communications, and any reliance on oral

communications is unwarranted."

Oliver Griffin, an attorney for the Sadiks and their corporate entities, responded to the

Demand for Compliance with a letter addressed to Ms. Doan. Mr. Griffin's letter, dated

March 20, 2006, stated that although the Sadiks had changed the menus at their restaurants

to comply with the Value Menu Memo, they believed that the restaurants "[fell] within the

allowable exceptions to BKC's policy directives found in the [Value Menu Memo]." The

letter continued:

Nevertheless, I understand that BKC has required my clients to make a formal application for the

exception, which BKC will then investigate [**9] the substance of before it issues an opinion - this

does not make sense for a number of reasons, which I would like to discuss with you over the

phone.

Therefore, upon receipt of this letter, please call me in order to discuss this matter, as well as

other matters relevant to the ongoing relationship between BKC and my clients.

Finally, and as you probably are aware, BKC has called a meeting between it and my

clients, which is tentatively scheduled to take place on April 1, 2006. I would like to know,

among other things, what BKC's agenda for this meeting is, in order that we can properly

prepare for it.

Mr. Griffin sent another letter to Ms. Doan dated April 12, 2006 stating that "my clients

qualify for an exemption from the [Value Menu] program, yet for reasons that are unclear,

BKC will not agree to the exemption."

Ms. Doan responded to Mr. Griffin on April 17, 2006 with the following email:

I am in receipt of your letter dated April 12, 2006. I have not had the opportunity to discuss the

Value Menu exemption request with my clients. [BKC] has specific guidelines regarding the BURGER

KING restaurants eligible for exemption. If the E-Z Eating Corporations submitted written requests

and [**10] back up data for an exemption at a restaurant or restaurants as required, and they did

not receive an exemption, then those restaurants do not meet the qualifications to be exempted

from the BK Value Menu. The BK Value Menu is a required menu item unless an exemption is

granted based on the defined criteria.

On April 19, 2006 Mr. Griffin wrote back: "[Ms. Doan], please discuss the value meal

exemption with your client and get back to me, as that was a key point of my letter." On

April 22, 2006 Ms. Doan replied: "I asked the [DVP], the local business person and the local

marketing person and nothing was submitted to them. [*1311] Can you tell me where they

sent the exemption request?" No further letter or email exchanges on this topic appear in the

record.

4. The Closing of Two Restaurants: BK # 12287 and BK # 12288

The # 12287 Franchise Agreement provided that the 8th Avenue location was to remain

open for business until January 11, 2011. 5 The # 12288 Franchise Agreement provided that

the 46th Street location was to remain open for business until August 3, 2019. In January

2007 the Sadiks stopped operating BK # 12287. Two months later, they stopped operating

BK # 12288.

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - Footnotes - - - - - - - - - - - - - - 5 We note that while BKC [**11] and the district court refer to January 11, 2011 as the end date of

the # 12287 Franchise Agreement, according to the Agreement itself January 15, 2011 is the end

date. Ultimately, however, this discrepancy does not affect our decision.

- - - - - - - - - - - - End Footnotes- - - - - - - - - - - - - -

In a letter to the Sadiks dated January 17, 2008 Ms. Doan formally declared the remaining

two Franchise Agreements terminated. Specifically, Ms. Doan stated that in ceasing

operations at BK # 12287 and BK # 12288 without BKC's written consent, the Sadiks had

breached the Franchise Agreements corresponding to those establishments. Ms. Doan stated

that in defaulting on two of their Franchise Agreements, the Sadiks had thus defaulted on

the Assistance Agreement itself pursuant to Section VII(B) of that document. Ms. Doan

invoked Section VIII of the Assistance Agreement to declare the remaining Franchise

Agreements terminated - that is, the # 11100 and # 13447 Franchise Agreements. The letter

informed the Sadiks that they were to cease operations at those two establishments and also

to cease using any of BKC's marks.

B. Procedure

On January 23, 2007 BKC sued over the premature closure of BK # 12287 - specifically,

BKC sued E-Z Eating 8th for breach of the [**12] # 12287 Franchise Agreement, and sued

the Sadiks for breach of their Guaranty of that Agreement. That case came before Judge

Cooke of the U.S. District Court for the Southern District of Florida (the "Cooke Action").

On April 25, 2007 BKC filed its Amended Complaint adding E-Z Eating 46th as a

defendant. The Amended Complaint sued E-Z 46th for breach of the # 12288 Franchise

Agreement, and the Sadiks for breach of their Guaranty of that Agreement. Appellants E-Z

8th, E-Z 46th, and the Sadiks counterclaimed against BKC for common law fraud, breach of

contract (specifically, for breaching Section 6(I) of the Franchise Agreements in imposing

the Value Menu), breach of implied duty of good faith and fair dealing (in imposing the

Value Menu), and promissory estoppel. 6

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - Footnotes - - - - - - - - - - - - - - 6 Appellants later voluntarily dismissed the counts for common law fraud and promissory estoppel

without prejudice.

- - - - - - - - - - - - End Footnotes- - - - - - - - - - - - - -

On November 30, 2007 BKC moved for summary judgment on its Amended Complaint and

on Appellants' Counterclaims. After BKC's Motion for Summary Judgment was briefed, but

before the district court's decision, BKC terminated the # 11100 and # 13447 Franchise

Agreements based on a cross-default provision in Section [**13] VII(B) of the Assistance

Agreement. On January 22, 2008 BKC filed a lawsuit against the Sadiks, E-Z Eating 41st,

and E-Z Eating 47th before Judge Jordan (the "Jordan Action") for claims of trademark

infringement and unfair competition, breach of the # 11100 and # 13447 Franchise

Agreements, breach of the Assistance Agreement, breach of the Promissory [*1312] Note,

breach of the # 11100 and # 13447 Guaranties, and breach of the 2005 Guaranty, all based

on the fact that BK # 11100 and BK # 13447 were still open for business even though BKC

had terminated the corresponding Franchise Agreements. BKC also filed a motion for a

preliminary injunction, requesting that Appellants cease operating BK # 11100 and BK #

13447 under the BKC name. 7 Appellants also filed a counterclaim in the Jordan Action

asserting claims for declaratory judgment, breach of contract, and breach of implied duty of

good faith and fair dealing.

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - Footnotes - - - - - - - - - - - - - - 7 The court granted the Motion for Preliminary Injunction on February 11, 2008, thus requiring

Appellants to close BK # 11100 and BK # 13447.

- - - - - - - - - - - - End Footnotes- - - - - - - - - - - - - -

On January 24, 2008 the Sadiks, E-Z Eating 41st, and E-Z Eating 47th filed a lawsuit

against BKC before Judge Ungaro (the "Ungaro Action"). They [**14] raised claims for

declaratory judgment, breach of contract (specifically, Section 6(I) of the Franchise

Agreements), and breach of the implied duty of good faith and fair dealing. 8 They also

sought injunctive relief in the Ungaro Action to prevent BKC from terminating the # 11100

and # 13447 Franchise Agreements and forcing them to close BK # 11100 and BK # 13447.

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - Footnotes - - - - - - - - - - - - - - 8 HN1 "Under Florida law, every contract contains an implied covenant of good faith and fair

dealing, requiring that the parties follow standards of good faith and fair dealing designed to

protect the parties' reasonable contractual expectations." Centurion Air Cargo, Inc. v. United Parcel

Serv. Co., 420 F.3d 1146, 1151 (11th Cir. 2005).

- - - - - - - - - - - - End Footnotes- - - - - - - - - - - - - -

On January 30, 2008 Judge Cooke consolidated the Cooke Action, the Jordan Action, and

the Ungaro Action - all three cases now fell under Case Number 07-20181, with Judge

Cooke presiding.

On May 22, 2008 the district court granted BKC's first Motion for Summary Judgment as to

liability only. The court held that E-Z 8 , E-Z 46 , and the Sadikth th s defaulted on the #

12287 and # 12288 Franchise Agreements in ceasing operations at BK # 12287 and BK #

12288 prior to the expiration of the Agreements [**15] without BKC's consent. In so

holding, the court rejected Appellants' affirmative defenses of waiver/estoppel, laches,

unclean hands, standing, impossibility of performance, and failure to attach a writing.

Further, the court granted summary judgment in BKC's favor on Appellants' Counterclaims

for breach of contract and breach of the implied duty of good faith and fair dealing.

BKC filed another motion for summary judgment on June 6, 2008, this time against all

Appellants in the now-consolidated case. Specifically, BKC's motion sought summary

judgment on these remaining claims: all claims originally raised in the Jordan Action, all

claims originally raised in the Ungaro Action, and BKC's requested damages in the original

Cooke Action. In an order dated July 25, 2008 the district court granted summary judgment

in BKC's favor on the claims in the Jordan and Ungaro Actions. The court also granted BKC

permanent injunctive relief prohibiting Appellants' unauthorized use of BKC's marks in

connection with BK # 11100 and BK # 13447. Regarding damages, the district court held

that Appellants owed BKC a total of $ 770,547.55 for past due royalties, outstanding

payments on the Promissory Note, [**16] and lost profits in connection with BK # 12287

and BK # 12288.

II. DISCUSSION

A. Standard of Review

HN2

"We review the trial court's grant or denial of a motion for summary

judgment [*1313] de novo, viewing the record and drawing all reasonable inferences in the

light most favorable to the non-moving party." Patton v. Triad Guar. Ins. Corp., 277 F.3d

1294, 1296 (11th Cir. 2002).

HN3

Under Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 56(c), summary judgment is proper "if the

pleadings, the discovery and disclosure materials on file, and any affidavits show that there

is no genuine issue as to any material fact and that the movant is entitled to judgment as a

matter of law." See Celotex Corp. v. Catrett, 477 U.S. 317, 322, 106 S. Ct. 2548, 91 L. Ed.

2d 265 (1986). "[A] party seeking summary judgment always bears the initial responsibility

of informing the . . . court of the basis for its motion, and identifying those portions of the

pleadings, depositions, answers to interrogatories, and admissions on file, together with the

affidavits, if any, which it believes demonstrate the absence of a genuine issue of material

fact." Id. at 323 (internal quotations omitted). If the movant succeeds in demonstrating the

absence of a material issue of fact, the burden [**17] shifts to the non-movant to show the

existence of a genuine issue of fact. See Fitzpatrick v. City of Atlanta, 2 F.3d 1112, 1116

(11th Cir. 1993). 9

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - Footnotes - - - - - - - - - - - - - - 9 We apply Florida law. HN4 "In a diversity case, a federal court applies the substantive law of the

forum state, unless federal constitutional or statutory law is contrary." Ins. Co. of N. Am. v. Lexow,

937 F.2d 569, 571 (11th Cir. 1991). The forum state here is Florida. The parties agreed in Section

21(C)(1) of all four Franchise Agreements that Florida law would govern. HN5 "[U]nder Florida law,

courts will enforce choice-of-law provisions unless the law of the chosen forum contravenes strong

public policy." Maxcess, Inc. v. Lucent Techs, Inc., 433 F.3d 1337, 1341 (11th Cir. 2005) (internal

quotations and citations omitted).

- - - - - - - - - - - - End Footnotes- - - - - - - - - - - - - B. Analysis

In this appeal, Appellants only raise two challenges to the district court's rulings. First, they

challenge the court's grant of BKC's motions for summary judgment, arguing a genuine

issue exists as to whether BKC "frustrated the essential purpose of the franchise agreements

. . . by arbitrarily and unreasonably refusing to grant the Appellants an available [Value

Menu] exception." Initial Br. at 2. Second, Appellants [**18] challenge the court's grant of

summary judgment in BKC's favor on their breach of implied covenant of good faith and

fair dealing claim. 10 Appellants seek reversal and remand "with instructions to proceed to

trial on the E-Z Defendants claim for breach of the implied covenant of good faith and fair

dealing." Id. at 34-35. Notably, Appellants do not challenge any of the district court's rulings

on damages. We address both prongs of Appellants' appeal below.

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - Footnotes - - - - - - - - - - - - - - 10 HN6 "A breach of the implied covenant of good faith and fair dealing is not an independent

cause of action, but attaches to the performance of a specific contractual obligation." Centurion Air

Cargo, 420 F.3d at 1151. Indeed, "[t]his court has held that a claim for a breach of the implied

covenant of good faith and fair dealing cannot be maintained under Florida law in the absence of a

breach of an express term of a contract." Id. at 1152.

- - - - - - - - - - - - End Footnotes- - - - - - - - - - - - - 1. BKC's Imposition of the Value Menu

Appellants argue that there is genuine issue of material fact as to whether they had a defense

to BKC's breach of contract claims - specifically, as to whether BKC frustrated the essential

purpose of the Franchise Agreements in imposing the Value Menu.

The district [**19] court held that BKC was entitled to impose its Value Menu on

Appellants by the terms of the Franchise Agreements. The court stated that Section 6(I)

gave BKC "discretion to decide whether to provide services and [Appellants] have not

pointed to a general failure [*1314] on behalf of BKC . . . which prevented them from

operating their franchises." May 22, 2008 O. at 12. The court also noted that Section 5(A) of

the Franchise Agreements "specifically require[s] [Appellants] to adhere to BKC's

comprehensive restaurant format and operating system." Id. at 12-13.

We agree with the district court on this point. Section 5(A) of the Franchise Agreements

provided that the franchisee "agrees that changes in the standards, specifications and

procedures may become necessary and desirable from time to time and agrees to accept and

comply with such modifications, revisions and additions to the MOD Manual which BKC in

the good faith exercise of its judgment believes to be desirable and reasonably necessary."

There is simply no question that BKC had the power and authority under the Franchise

Agreements to impose the Value Menu on its franchisees.

2. The Value Menu Exception

Appellants also argue that there [**20] is a genuine issue of material fact as to whether

BKC breached Florida's implied covenant of good faith and fair dealing by denying them an

exception to the Value Menu. However, we must answer two preliminary questions before

we can address that issue. First, we must determine if Appellants may raise this issue on

appeal. Second, we must determine if a genuine issue exists as to whether Appellants

properly applied for an exception to the Value Menu - if so, we can determine whether there

exists a genuine issue as to whether BKC should have granted such an exception.

a. Can Appellants raise this issue on appeal?

Appellants argue that a genuine issue exists as to whether BKC breached Florida's implied

covenant of good faith and fair dealing by denying them a Value Menu exception. As noted

above, under Florida law this cause of action requires a corresponding breach of an express

contract term. See Centurion Air Cargo, 420 F.3d at 1151-52. Here, Appellants claim that in

imposing the Value Menu and refusing to grant an exception, BKC breached Section 5(A)

of the Franchise Agreements. BKC responds that Appellants cannot raise this argument on

appeal because they did not raise it to the district [**21] court 11 - that is, Appellants only

argued breach of Section 6(I), not Section 5(A). Whether the issue was raised under a

specific paragraph of the contracts simply makes no difference - it clearly was raised and

resolved. Consequently, we find no merit in this argument.

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - Footnotes - - - - - - - - - - - - - - 11 HN7 "Arguments raised for the first time on appeal are not properly before this Court." Hurley

v. Moore, 233 F.3d 1295, 1297 (11th Cir. 2000).

- - - - - - - - - - - - End Footnotes- - - - - - - - - - - - - -

b. Is there a genuine issue of material fact as to whether Appellants properly applied for an

exception?

BKC argues that even if Appellants are allowed to raise the issue of a Value Menu

exception, the district court judgment stands. This is because, BKC argues, Appellants

conceded that they did not apply for such an exception in writing to the Division VicePresident Jim Joy, as the Value Menu memorandum and Demand for Compliance explicitly

required. Appellants respond that they did create a genuine issue as to whether they properly

applied in writing for a Value Menu exception. They also argue that in any case, BKC

waived the "in writing" requirement by meeting with Mr. Sadik in person.

[*1315] We find that Appellants failed to establish a genuine issue as to whether they

submitted a written [**22] request for a Value Menu exception. Mr. Sadik admitted in his

deposition that he did not submit a written exception request, even though he was aware that

the Value Menu Memo required exceptions to be requested in writing. See D.E. # 128.

Specifically, Mr. Sadik testified that at first he did not submit a written request because he

"assumed all New York was out. It says in-line stores. My stores are in-line." Mr. Sadik

further testified that he only applied for the exception "verbally" because he "assumed

verbally was fine." When asked whether "anybody ever told [him] not to submit the written

request," Mr. Sadik stated "no."

Although Appellants point to Mr. Griffin's two letters as support that they did submit a

written exception request, neither letter creates a genuine issue for several reasons. First, the

letters were addressed to Ms. Doan and not to Division Vice-President Jim Joy, as the Value

Menu Memo and Demand for Compliance required. Second, neither letter actually asked for

a specific exception, such as the "in-line" exception - indeed, neither letter specified which

of the three exceptions the Sadiks sought, or why they qualified under a particular

exception. Mr. Griffin's [**23] March 20 letter spoke generally of "the allowable

exceptions," stating only: "it is our position that the EZ restaurants fall within the allowable

exceptions to BKC's policy directives found in the [Value Menu Memo]." Moreover, Mr.

Griffin's March 20 letter appears to expressly not comply with the formal application

requirement: "I understand that BKC has required my clients to make a formal application

for the exception, which BKC will then investigate the substance of before it issues an

opinion - this does not make sense for a number of reasons, which I would like to discuss

with you over the phone." In his April 12 letter Mr. Griffin still did not mention which

exception his clients sought, or why. In fact, in that letter Mr. Griffin seemed to assume the

Sadiks had already applied for an exception: "my clients qualify for an exemption from the

[Value Menu] program, yet for reasons that are unclear, BKC will not agree to the

exemption." Third, these letters did not include back-up documentation, as the Demand for

Compliance explicitly required.

As for Appellants' argument that BKC waived its requirement for a written exception

request, we do not accept it. HN8 Under Florida law, "waiver" [**24] is defined as "the

voluntary and intentional relinquishment of a known right or conduct which implies the

voluntary and intentional relinquishment of a known right." Raymond James Fin. Servs.,

Inc. v. Saldukas, 896 So. 2d 707, 711 (Fla. 2005). Further, according to Florida law,

"[c]onduct may constitute waiver of a contract term, but such an implied waiver must be

demonstrated by clear evidence." BMC Indus., Inc. v. Barth Indus., Inc., 160 F.3d 1322,

1333 (11th Cir. 1998); see also, e.g., Kirschner v. Baldwin, 988 So. 2d 1138, 1142 (Fla. 5th

DCA 2008) ("When a waiver is implied, the acts, conduct or circumstances relied upon to

show waiver must make out a clear case."); Hale v. Dep't of Revenue, 973 So. 2d 518, 522

(Fla. 1st DCA 2007) ("If a party relies upon the other party's conduct to imply a waiver, the

conduct relied upon to do so must make out a clear case of waiver.") (internal quotations

and citation omitted).

Here, there is scant evidence regarding a meeting between Mr. Sadik and BKC

representatives at which they discussed Appellants' eligibility for a Value Menu exception too scant to create a genuine issue. Appellants have not alleged when exactly the meeting

was, where [**25] it was held, who specifically attended, what the [*1316] attendees said,

or what sort of information was exchanged. Indeed, although Mr. Sadik referred to such a

meeting in an affidavit, he said only this: "I met with the FBL and other BKC

representatives and explained to them that the Value Menu was going to drive me into

insolvency . . . ." D.E. # 115-2. Further, he stated: "[t]hese BKC representatives told me that

they were going to report back to BKC corporate and then give me an answer as to whether

or not I would be excepted from the Value Menu (as in line stores qualify, and my stores

were in line stores)." Id. 12

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - Footnotes - - - - - - - - - - - - - - 12 Mr. Griffin also submitted an affidavit mentioning that Mr. Sadik met with BKC representatives

and that Mr. Griffin provided BKC representatives with the Sadiks' "financials" and documentation.

However, this affidavit is far too vague to create a genuine issue as to whether BKC waived its

written exception requirement. As an aside, we are surprised at Appellants' reliance on Mr. Griffin's

affidavit since this could disqualify him as their attorney at trial. See Fla. Stat. Bar Rule 4-3.7 ("A

lawyer shall not act as advocate at a trial in which the lawyer is likely to be a [**26] necessary

witness on behalf of the client" except in certain limited circumstances).

- - - - - - - - - - - - End Footnotes- - - - - - - - - - - - - -

In contrast to Appellants' vague evidence of a meeting in which BKC waived its written

request requirement, every communication in evidence from BKC to the Sadiks on this topic

invoked that requirement. 13 Indeed, as is apparent from Ms. Doan's email exchange with

Mr. Griffin, as late as April 22, 2006 BKC representatives still assumed any Value Menu

exception would be requested in writing. On that date, Ms. Doan wrote to Mr. Griffin: "I

asked the [DVP], the local business person and the local marketing person and nothing was

submitted to them. Can you tell me where [the Sadiks] sent the exemption request?" Mr.

Sadik also admitted in his deposition that no one ever told him not to submit a written

request. We find there is simply not enough evidence to create a genuine issue as to whether

BKC waived its requirement that the Sadiks request a Value Menu exception in writing.

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - Footnotes - - - - - - - - - - - - - - 13 This evidence includes the Value Menu Memo itself, the Demand for Compliance letter, and Ms.

Doan's April 17, 2006 and April 22, 2006 emails. See supra p. 6-9.

- - - - - - - - - - - - End Footnotes- - - - - - - - - - - - - -

Because Appellants failed to create a genuine issue as to whether they [**27] properly

asked for a Value Menu exception, we need not address whether BKC should have granted

Appellants such an exception.

III. CONCLUSION

In sum, we find that BKC was clearly entitled to impose its Value Menu on Appellants, and

Appellants failed to establish a genuine issue of material fact as to whether they properly

applied for an exception from the Value Menu. Accordingly, the judgment of the district

court is

AFFIRMED.