Extract

advertisement

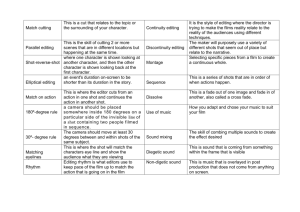

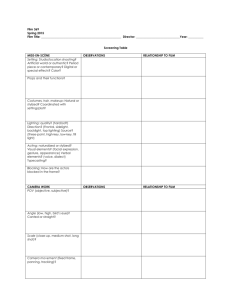

Chapter 8 – Looking at Movies What Is Editing? Editing, the basic creative force of cinema, is the process by which the editor combines and coordinates individual shots into a cinematic whole. Orson Welles said, "For my vision of the cinema, editing is not simply one aspect. It is the aspect.'" The technique (or method) is the actual joining together of two shots- often called cutting or splicing because, prior to the era of digital editing software, the editor had to first cut (or splice) each shot from its respective roll of film before gluing or taping all the shots together. The craft (skill) is the ability to join shots and produce a meaning that does not exist in either one of them individually. The art of editing, Dancyger declares, "occurs when the combination of two or more shots takes meaning to the next level- excitement, insight, shock, or the epiphany of discovery.'" The basic building block of film editing is the shot (as defined in Chapter 6), and its most fundamental tool is the cut. Each shot has two explicit values: the first value is determined by what is within the shot itself; the second value is determined by how the shot is situated in relation to other shots. The first value is largely the responsibility of the director, cinematographer, production designer, and other collaborators who determine what is captured on film. The second value is the product of editing. The tendency of viewers to interpret shots in relation to surrounding shots is the most fundamental assumption behind all film editing. Editing takes advantage of this psychological tendency in order to accomplish various effects: to help tell a story, to provoke an idea or a feeling, or to call attention to itself as an element of cinematic form. No matter how straightforward a movie may seem, you can be sure that (with very rare exceptions) the editor had to make difficult decisions about which shots to use and how to use them. The Film Editor The person primarily responsible fo r such decisions is the film editor." The bulk of the film editor's work occurs after the director and collaborators have shot all of the movie's foo tage. In many major film productions, however, the editor's responsibilities as a collaborator begin much earlier in the process. A typical Hollywood movie made in the 1940s and 1950s runs approximately 1 to 1'1. hours long and is composed of about 1,000 shots; today's movies typically run between 2 and 3 hours, but because they consist of approximately 2,000 to 3,000 shots, they have a faster tempo than earlier films had. That factor alone increases the editor's work of selecting and arranging the footage. It is not uncommon for the ratio between unused and used footage in a Hollywood production to be as high as 20 to 1, meaning that for every "1" minute you see on the screen, 20 minutes of footage has been discarded. Perhaps the best-known extreme example is Francis Ford Coppola's Apocalypse Now (1979). Working for two years, Walter Murch and his editorial team eventually shaped 235 hours of footage into a (mostly) coherent movie that runs 2 hours 33 minutes (resulting in a ratio of unused to used footage of just under 100 to I). Clearly, the creative power of the editor comes close to that of the director. Consider, the challenges faced by David Tedeschi, the editor of Martin Scorsese's Shine Q Light (2008), which documents two Rolling Stones concerts in New York. Robert Richardson, the director of photography, supervised eighteen camera operators and dozens of camera assistants and lighting technicians. The editor was faced with selecting and arranging the thousands of feet of live footage that, in the finished movie, is intercut with archival footage of the group's career. The Editor's Responsibilities The editor is responsible for constructing the overall form of the movie and helping the production team realize its collective artistic vision by selecting, manipulating, and assembling its constituent visual and aural parts. Specifically, the editor is responsible for managing the following aspects of the final film: > spatial relationships between shots > temporal relationships between shots > the overall rhythm of the film Spatial Relationships between Shots One of the most powerful effects of film editing is the creation of a sense of space in the mind of the viewer. When we are watching any single shot from a film, our sense of the overall space of the scene is necessarily limited by the height, width, and depth of the film frame during that shot. But as other shots are placed in close proximity to that original shot, our sense of the overall space in which the characters are moving shifts and expands. The juxtaposition of shots within a scene can cause us to have a fairly complex sense of that overall space (something like a mental map) even if no single shot discloses it). Countless films- especially historical dramas and science-fiction films- rely heavily on the power of editing to fool us into perceiving their worlds as vast and complete even as we are shown only tiny fractions of the implied space. Because our brains effortlessly make spatial generalizations from limited visual information, George Lucas was not required, for example, to build an entire to-scale model of the Millennium Falcon to convince us that the characters in Star Wars are flying (and moving around within) a vast spaceship. Instead, a series of cleverly composed shots filmed on carefully designed (and relatively small) sets could, when edited together, create the illusion of a massive, fully functioning spacecraft. The placement of one shot of a person's reaction (perhaps a look of concerned shock) after a shot of an action by another person (falling down a flight of stairs) immediately creates in our minds the thought that the two people are occupying the same space, that the person in the first shot is visible to the person in the second shot, and that the emotional response of the person in the second shot is a reaction to what has happened to the person in the first shot. The central discovery of Lev Kuleshov, the Soviet film theorist was that these two shots need not have any actual relationship at all to one another for this effect to take place in a viewer's mind. The effect of perceiving such spatial relationships even when we are given minimal visual information or when we are presented with shots filmed at entirely different times and places is sometimes called the Kuleshov effect. Editing Techniques That Maintain Continuity In addition to the fundamental building blocks- the master shot and maintaining screen direction with the 180-degree system- various editing techniques are used to ensure that graphic, spatial, and temporal relations are maintained from shot to shot. Shot/Reverse Shot A shot/reverse shot, one of the most common and familiar of all editing patterns, is a technique in which the camera (and editor) switches between shots of different characters, usually in a conversation or other interaction. When used in continuity editing, the shots are typically framed over each character's shoulder to preserve screen direction. Thus, in the first shot the camera is behind character A, is looking right, and records what character B says to A; in the second shot, the camera is behind character B, who is looking left, and records that character's response. Match Cuts Match cuts- those in which shot A and shot B are matched in action, subject, graphic content, or two characters' eye contact help create a sense of continuity between the two shots. Match-on-Action Cut A match-on-action cut shows us the continuation of a character's or object's motion through space without actually showing us the entire action. It is a fairly routine editorial technique for economizing a movie's presentation of movement. Of course, the matchonaction cut has both expressive and practical uses. In David Lean's Lawrence of Arabia (1962; editor: Anne V. Coates), there is an elliptical match cut that both wows us and moves the story forward. Indeed, it's a match cut on a match. T. E. Lawrence (Peter O'Toole) receives a charge to make a perilous journey from Mr. Dryden (Claude Rains), a British officer in Cairo; as he does so, he lights Dryden's cigarette, holds the match up and watches the flame burn closer and closer to his fingers (he enjoys such pain), responds to Dryden's skepticism about the assignment by saying, "No, Dryden, it's going to be fun," and blows out the match. The editor uses a match cut to the rising of the sun above the desert horizon. It's one of the great pieces of editing in film history, about which film critic Anthony Lane writes: "It was a moment that Steven Spielberg saw at the age of fifteen, and which, he says, ignited his determination to make films. If you don't get this cut, if you think it's cheesy or showy or over the top, and if something inside you doesn't flare up and burn at the spectacle that Lean has conjured, then you might as well give up the movies.'" Graphic Match Cut In a graphic match cut, the similarity between shots A and B is in the shape and form of what we see. In this type of cut, the shape, color, or texture of objects matches across the edit, providing continuity. The prologue of Stanley Kubrick's 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968; editor: Ray Lovejoy) contains a memorable example of a graphic match cut in which the action continues seamlessly from one shot to the next: a cut that erases millions of years, from a bone weapon of the Stone Age to an orbiting craft of the Space Age. The weapon and the spacecraft match not only in their tubular shapes but also in their rotations. Graphic matches often exploit basic shapes squares, circles, triangles- and provide a strong visual sense of design and order. For example, at the end of the shower murder sequence in Psycho (1960; editor: George Tomasini), Hitchcock matches two circular shapes: the eye of Marion Crane (Janet Leigh), tears streaming down, with the round shower drain, blood and water washing down- a metaphorical visualization of Marion's life ebbing away. Eye-fine Match Cut The eye-line match cut joins shot A, a point-of-view shot of a person looking offscreen in one direction, and shot B, the person or object that is the object of that gaze. Other Transitions between Shots The Jump Cut The jump cut presents an instantaneous advance in the action- a sudden, perhaps illogical, often disorienting ellipsis between two shots caused by the absence of a portion of the film that would have provided continuity. Because such a jump in time can occur either on purpose or because the filmmakers have failed to follow continuity principles, this type of cut has sometimes been regarded more as an error than as an expressive technique of shooting and editing. In one of the first major films of the French New Wave- Breathless (1960; editors: Cecile Decugis and Lila Herman)-Jean-Luc Godard employs the jump cut deliberately and effectively to create the movie's syncopated rhythm. Fade The fade-in and fade-out are transitional devices that allow a scene to open or close slowly. In a fade-in, a shot appears out of a black screen and grows gradually brighter; in a fade-ou t, a shot grows rapidly darker until the screen turns black for a moment. Traditionally, such fades have suggested a break in time, place, or action. Dissolve Also called a lap dissolve, the dissolve is a transitional device in which shot B, superimposed, gradually appears over shot A and begins to replace it midway through the process. Like the fades described in the preceding section, the dissolve is essentially a transitional cut, primarily one that shows the passing of time or implies a connection or relationship between what we see in shot A and shot B. But it is different from a fade in that the process occurs simultaneously on the screen, whereas a black screen separates the two parts of the fade. Fast dissolves can imply a rapid change of time or a dramatic contrast between the two parts of the dissolve. Slow dissolves can mean a gradual change of time or a less dramatic contrast. Wipe Like the dissolve and the fade, the wipe is a transitional device- often indicating a change of time, place, or location- in which shot B wipes across shot A vertically, horizontally, or diagonally to replace it. A line between the two shots suggests something like a windshield wiper. A soft-edge wipe is indicated by a blurry line; a hard-edge wipe, by a sharp line. A jagged line suggests a more violent transition. Although the device reminds us of early eras in filmmaking, directors continue to use it. In fact, some directors use it to call to mind these earlier eras. In Star Wars (1977; editors: Richard Chew, Paul Hirsch, and Marcia Lucas), for example, George Lucas refers to old-time science-fiction serials that inspired him by using a right-to-Ieft horizontal wipe as a transition between the scene in which Luke Skywalker (Mark Hamill) meets Ben Obi-Wan Kenobi (Alec Guinness) and a scene on Darth Vader's (David Prowse) battle station. Parallel Editing Parallel editing is the cutting together of two or more lines of action that occur simultaneously at different locations or that occur at different times. Although the terms parallel editing, crosscutting, and intercutting are often used interchangeably, you should understand the differences among them. Parallel editing is generally understood to mean two or more actions happening at the same time in different places, as in the "Baptism and Murder" scene in Francis Ford Coppola's The Godfather Crosscutting refers to editing that cuts between two or more actions occurring at the same time, and usually in the same place. Iris Shot In the iris shot, everything is blacked out except for what is seen through a keyhole, telescope, crack in the wall, or binoculars, depending on the actual shape of the iris or the point of view with which the viewer is expected to identify. Sometimes, of course, the point of view is that of the director, who wants to call our attention to this heightened way of seeing. In The Night of the Hunter (1955; editor: Robert Golden), Charles Laughton uses the iris-out both for its own sake and perhaps as homage to Griffith and Lillian Gish, who plays a main character in the movie and was a frequent star of Griffith's films. Freeze-Frame The freeze-frame (also called stop-frame or hold-frame) is a still image within a movie, created by repetitive printing in the laboratory of the same frame so that it can be seen without movement for whatever length of time the filmmaker desires. It stops time and functions somewhat like an exclamation point in a sentence, halting our perception of movement to call attention to an image. Split Screen The split screen, which has been in mainstream use since Phillips Smalley and Lois Weber's Suspense (1913), produces an effect that is similar to parallel editing in its ability to tell two or more stories at the same cinematic time, whether or not they are actually happening at the same time or even in the same place. Among its most familiar uses is to portray both participants in a telephone conversation simultaneously on the screen. Unlike parallel editing, however, which cuts back and forth between shots for contrast, the split screen can tell multiple stories within the same frame. Guiding questions: What is editing? What are 3 key functions of editing? How many shots do today’s movies contain compared to those made in the 1930’s and 1940’s. What about films made by the Lumiere Brothers? In Apocalypse Now, how many hours of footage did the editor, Walter Murch have to deal with? Do you agree with the statement – “the creative power of the editor comes close to that of the director. How many cameras did Martin Scorcese use for the Rolling Stones film – Shine a Light? Which 3 key aspects of final film is the editor responsible for managing? What is a flashback? What is a flash forward? Give two film examples. Define ellipsis What is montage? How does an editor control the rhythm of a sequence? What is the purpose of continuity editing? What is a mater shot/cover shot? What is the 180 degree rule ? What is meant by shot/reverse shot ? What are match cuts and what are the different types of match cut? Explain parallel editing and cross cutting What is a jump cut? Make sure you understand the following types of edit and how each might be used in a film: Also make sure you know how to use them in FCP: Cut Fade in and fade out Dissolve Wipe Iris shot Freeze Frame Split screen