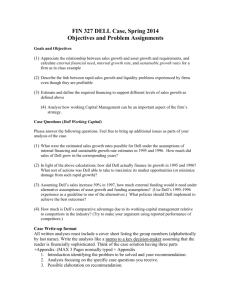

Sales Growth and Employment Growth of Dell during Internet Period

advertisement