Οικονομικό Πανεπιστήμιο Αθηνών Άνοιξη 2012

Οικονομικό Πανεπιστήμιο Αθηνών

Τμήμα Οικονομικής Επιστήμης

Χρηματοοικονομικές αγορές και εταιρική διακυβέρνηση

Άνοιξη 2012

Lecture 5: Debt and equity.

Debt as a governance Mechanism.

Debt is often viewed as a disciplining device especially if its maturity is relatively short.

It forces the firm to pay with cash flow.

As a result, managers are not tempted to use them for themselves.

There is always the fear of illiquidity.

Under financial distress, but in the absence of liquidation, creditors acquire control rights over the firm (they can force the firm into bankruptcy).

Debtholders are more conservative than equityholders. Therefore, they limit risk by cutting investment and new projects.

Recall: In leveraged buyouts the acquisition of another company using a significant amount of borrowed money (bonds or loans) to meet the cost of acquisition. Often, the assets of the company being acquired are used as collateral for the loans in addition to the assets of the acquiring company.

Debt: A claim to a predetermined level of firm’s income.

Equity: Profits beyond that level.

Priority of claims:

Secured debt > Ordinary debt > Subordinated (junior) debt > Preferred stock > Common stock.

Secured debt: When debt is no fully reimbursed, secured debtholders can seized the assets used as collateral as part of their lending contract.

Preferred stock: Like debt, its holders are entitled to a fixed predetermined repayment.

However, non-repayment does not trigger default. No voting rights.

Modigliani Miller Theorem: Under certain conditions, the total value of the firm (value of claims over the firm’s income) is independent of the financial structure.

(It does not matter if the firm's capital is raised by issuing stock or selling debt. It does not matter what the firm's dividend policy is).

That is: The level of debt, the split of debt into claims with different levels of collateral and different seniorities in the case of bankruptcy etc have no impact on total value of the firm. Decisions concerning the financial structure affect only how the income that the firm generates is shared.

Assumptions: Absence of taxes, bankruptcy costs, and asymmetric information, and in an efficient market.

V

E

= E (max(0, R - D))

Equity holders receive nothing until the debt is paid, and all revenues after that level.

V

D

= E (min(R, D))

The opposite with debt holders.

V

E

+ V

D

= E (max(0, R - D)) + E (min(R, D)) = E (R) is independent of D.

R: Revenues (random variable)

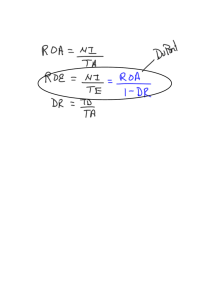

Figure 2.1

Example:

Say V

U

= 100.000 and return is 1%. I.e. total return is 1000. 1% of return is 10.

For the Levered firm, V

L

= 100.000 and return is 1%. Also, 50% is equity and 50% is debt.

Let U be an unleveraged firm. Total value of equity E

U

= Total value of firm V

U

.

Let L be a levered firm. Total value of stock E

L

= Value of firm – value of debt D

L

:

E

L

= V

L

– D

L

.

Case (a)

The unleveraged firm has total return 1000. It distribute all total amount of 1000 to equity holders. We have:

If invest in U, buy 1%:

Spend 1000

0.01 V

U

,

Return

0.01 * profits 10

For the leveraged firm: I buy 1% of its debt (spend 500) and 1% of its equity (spend 500).

The leveraged firm first pays the interest for its debt. That is, it pays 500 for interest. It then pays 1000 – 500 = 500 to equity holders.

If buy 1% of both D, E

Of the Levered firm:

0.01 D

0.01 E

L

L

, 0.01 * interest

0.01 * (profits – interest)

5

10-5

Both investments offer the same payoff. That means that the two firms have the same value: V

U

= V

L

as the Modigliani Miller Theorem shows.

Case (b)

If buy 1% of E of the Levered firm:

Spend 500

Also, equivalently, I can borrow 0.01 D

L

(borrow 500) and purchase 0.01 stock of the unlevered firm (use 500 from your own funds).

Borrow 0.01D

L

, use

Also your money

0.01 E

L

0.01 (V

L

- D

L

)

0.01 * (profits – interest) 5

-0.01 * interest

0.01 * profits

-5

10

-0.01 D

L

,

0.01V

U and buy 1% of U.

Borrow 500

Use own 500

Total 0.01(V

U

- D

L

) 0.01 * (profits - interest) 5

The last two strategies offer the same payoff: 0.1 * (profits – interest). They should have the same cost: 0.01(V

U

- D

L

) = 0.01 (V

L

- D

L

), that is V

U

= V

L

Financial instruments

Financial instruments can be categorized by "asset class" depending on whether they are equity based (reflecting ownership of the issuing entity) or debt based (reflecting a loan the investor has made to the issuing entity).

Debt instruments

Get a bank loan, issue a bond etc.

Credit analysis: Lenders perform a credit analysis: They analyze the borrower’s financial data (capital structure, liquidity etc), they estimate the market value of assets, the quality of the management.

Also, rating agencies perform credit analysis: They use grades to measure the credit worthiness of issuers and securities.

US government bonds and bonds issued by government sponsored enterprises (GSE's) are often considered to be in a zero-risk category above AAA; and categories like AA and A may sometimes be split into finer subdivisions like "AA-" or "AA+".

The categories are in general:

AAA, AA, A, BBB, BB, B, CCC, CC. C, D (default).

The grades reflect an estimate of the likelihood of default. For example: The cumulative default rate over the first 10 years of a bond’s life was (in 1989) 0.1% for an AAA rated bond and 31.9% for a B rated bond.

Bonds rated BBB and higher are called investment grade bonds.

Bonds rated lower than investment grade on their date of issue (bonds with grade BB or lower) are called speculative grade bonds, derisively referred to as “junk” bonds.

Criticism:

Credit rating agencies do not downgrade companies promptly enough . For example,

Enron's rating remained at investment grade four days before the company went bankrupt, despite the fact that credit rating agencies had been aware of the company's problems for months

Large corporate rating agencies have been criticized for having too familiar a relationship with company management .

Junk Bonds:

A junk bond (or high yield bond) is a bond that is rated below investment grade (“BB” and “B” categories as determined by rating agencies) at the time of purchase. These bonds have a higher risk of default or other adverse credit events, but typically pay higher yields than better quality bonds in order to make them attractive to investors.

Junk bonds became ubiquitous in the 1980s, through the efforts of investment bankers like Michael Milken, as a financing mechanism in mergers and acquisitions. In a leveraged buyout (LBO) an acquirer would issue junk bonds to help pay for an

acquisition and then use the target's cash flow to help pay the debt over time.

The low-rated bonds offer higher promised returns but have a higher expected probability of default, which means that a greater proportion of their expected return comes from interest payments rather than principal. As a result, they are less sensitive to interest rate swings, allowing a high-risk company to more easily refinance its debt even if interest rates have increased.

The analysis of high-yield debt has much in common with equity analysis, because the viability of the company and its future cash flows determine whether it will be able to repay the debt.

Junk bonds are still used to finance capital intensive industries such as telecommunications and oil and gas sectors.

Global issuance of high yield bonds more than doubled in 2003 to nearly $146 billion in deals issued from less than $63 billion in 2002, although this is less than the record of

$150 billion in 1998.

As the lower-rated debt typically offers a higher yield, it makes speculative bonds attractive investment vehicles for certain types of financial portfolios and strategies. On the other hand, many pension funds and other investors are prohibited in their by-laws from investing in bonds which have ratings below a particular level. As a result, the lower-rated securities may be harder to sell.

Equity instruments

Start-up financing: Venture capitals provide finance for young high-risk firms. Venture capital investments are generally made as cash in exchange for shares in the invested company. It is typical for venture capital investors to identify and back companies in high technology industries such as biotechnology and ICT (information and communication technology).

Venture capitals monitor the firm, bring managerial and technical expertise, industry contacts as well as capital to their investments.

Venture capitals generate a return through an eventual realization event such as an IPO or trade sale of the company.

Initial (IPO) and seasoned public offerings

When a company (called the issuer ) issues common stock or shares to the public for the first time. They are often issued by smaller, younger companies seeking capital to

expand, but can also be done by large privately-owned companies looking to become publicly traded.

Initially, equity is held by one or few entrepreneurs. Then, they may raise equity capital from a small number of investors through a private placement; alternatively, they may have a privileged relationship with a bank.

Then, the firms go public.

Benefits:

• Bolster and diversify equity base (entrepreneurs may exit the firm easier)

• Enable cheaper access to capital

• Exposure and prestige

• Attract and retain the best management and employees

• Facilitate acquisitions

• Create multiple financing opportunities: equity, convertible debt, cheaper bank loans, etc.

Costs:

• The procedure is costly. The firms suffer transaction costs (underwriting and legal fees).

• Firms provide information about their condition.

Procedure: They issue a fixed number of shares at a prespecified price).

Finally, it may then conduct secondary or seasoned public offerings.

References

Richard Brealey, Stewart Myers and Franklin Allen, “Corporate finance,” McGraw Hill

2006, Chapter 17.

Jean Tirole, “The theory of corporate finance,” Princeton University Press 2006, Chapter

2.