Sarah and Madeline's Family and Housing Outline

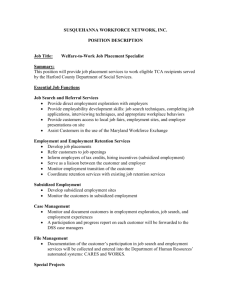

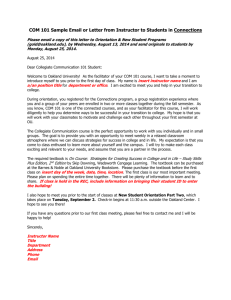

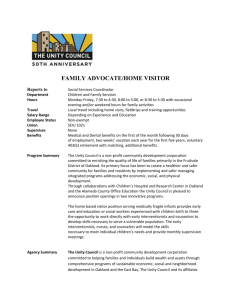

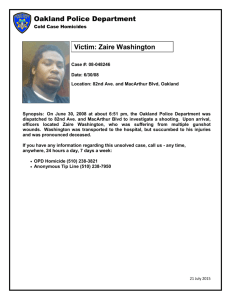

advertisement