A Covered Wagon Trek As a teenager, my mother

advertisement

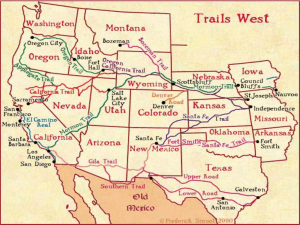

A Covered Wagon Trek As a teenager, my mother lived on a horse ranch along the Oklahoma /Arkansas border. Her stepfather was having some success raising Hambletonian race horses. Her real father had died when she was a baby, and her mother had struggled to support herself and her two children for 7 years before she had remarried. Her stepfather, King, had tried first one farm then another in Iowa, Missouri, Kansas and Oklahoma, with little success. But he seemed to have a gift with raising trotters. He was finally making headway. Then, one night, all that changed. The barn burned, and almost all the stock with it. The screams of the horses were horrible as they writhed and reared on the other side of the barred door that was too engulfed in flames to go near. In the morning, my mother and her parents, her two younger halfbrothers and the hired hands mourned the loss of the animals they had known and loved, and the livelihood they had provided. Examination of the ruins showed that their pet donkey, that could unbolt any gate and untie any knot, had in fact untied all the horses and opened their stalls to get them out of the inferno, but was stymied by the exterior barn door, barred from the outside. A charred dune of horseflesh stood testament inside the burned door. Everyone was devastated. The family was essentially destitute. There was nothing left for them here. They would lose the ranch. They would lose everything. They would have to start over, and they had nothing to start over with except their own spirits, and determination. They took stock of what they had. The fire had not reached the house. They would sell their furnishings, and just keep enough of the essentials to survive. They had a good stout wagon, with a canvas canopy. They had two team of oxen that had been in the pasture during the fire, and a few cows, chickens and pigs. My mother’s older brother, Albert, had left home the year before, and gone to California to work for the railroad. He wrote that California re ally was the land of milk and honey. They packed what they could into the wagon, and turned their back on Arkansas. It was the spring of 1914. They traveled through Kansas and Colorado, and although they didn’t have to contend with hostile Indians or bandits, their passage was not easy, nor were they greeted kindly along the way. Unlike the pioneers of the previous century, who crossed open plains, with plentiful grazing available, they could seldom travel across country, but followed rough roads and unpaved highways, hemmed by barbed wire fences, with only patches of grasses here and there to feed their stock. As they crossed the Rockies, the weather was hot, the water scarce, and hospitality non-existent. They had to buy every drop of water or morsel of grain or hay for their animals, and their own supplies of food were nearly gone. As was their cash. They had been traveling two days since their oxen had had a real feed, and the poor animals, thin from the weeks of hauling the wagon, were exhausted. The straggling cows had long since ceased giving significant milk. King thought they had left Colorado behind, and was glad of it. They had received not a civil word nor a helping hand from a human in the whole state. Even the dogs were vicious. They were now proceeding down a steep canyon road, and could occasionally catch glimpses and hints that a broad valley lay ahead and below them. Then, downhill and off to the right, they saw an approaching wagon, pulled by four horses, and driven by a bearded man in a dusty flat brimmed hat. The wagon was piled high with hay. As his wagon reached the main road, the man reined in and waited for their trudging oxen to come even with him. King halted the oxen and climbed down from the wagon and hailed the bearded man. He asked if he could buy some hay for his stock. The man removed his hat, wiped his forehead and neck with his bandanna, squinted at the sun, hocked and spat, looked down at King and said, ‘You sure as hell can’t buy any of my hay.’ The whole family thought, ‘Oh, no. Not again.’ This is the way they had been treated for weeks. Biting his tongue, King turned to their wagon. But before he could lift himself back to the seat, the bearded man reached for his pitch fork, clamped to his rack and climbed on top of the mound and began forking down huge loads of golden hay to the ground before the oxen. ‘You can’t buy my hay, but you can have as much as you need for that sorry looking bunch of critters.’ Then he turned to my mother and her little brothers and pointed behind him, ‘Young’uns, there’s a spring of cool water just beyond those green willows. Lead your cows there and bring pails of water back here for the oxen. It’s a little rough to take the wagon there. We’ll just unhitch the team and give them a rest for a while. They look like they've been pullin' a piece.’ The family was overwhelmed. After weeks of hardship, to be greeted with this kindness brought lumps to their throats and tears to their eyes. After the cattle had eaten and been watered and were rested sufficiently, the team was re-hitched, and the generous farmer asked little Oliver and Frank to ride with him, which meant my mother could ride in their wagon, instead of walk, as she had done for the last thousand miles or so. He insisted that the family follow him down to his farm. He would not hear of them going further, nor would he let them camp outside, as they had done for these months. There would be a nourishing supper and hot baths in the nickel plated tub behind the screen in the kitchen. His wife and daughters scurried and clucked to make them comfortable. His sons saw to their stock, corralling them and feeding them extra grain. His children slept that night on the floor so that tired strangers could sleep in good beds on clean sheets. This was Mona, Utah. Mount Nebo towered to the east. These were the first Mormons my mother had met. This was not Colorado. This was not California. But it would be home for a while.