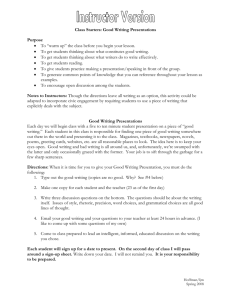

Creating Presentation Slides: A Study of User Preferences for

advertisement