Great Expectations Reviewed

advertisement

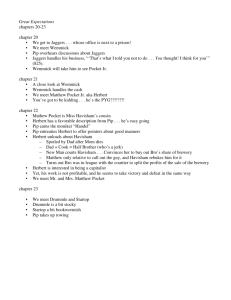

Great Expectations Reviewed Anonymous It has been said nobody ever wrote a perfect novel, except Charles Dickens. It has been said nobody ever wrote a perfect novel, except Charles Dickens. Certainly his popularity stems from the meticulous care with which he treats his characters; Lev Tolstoy went so far as to call this regard the author held for his creations to be 'love' (Calder, 11). Dickens' caricatures of the men and women of Victorian society ring true because the circumstances of his London are in so many ways comparable to modern Western societies. Dickens' criticisms of Victorian England are no less harsh than Karl Marx's dialectic attack, or Friedrich Nietsche's epistemological one; Great Expectations is a superbly crafted freeform philosophical treatise; Dickens was a master novelist, and used the form to its utmost to effect a meaningful study of how one should live in such a world. Because of its relevance to contemporary society, moreover, it is important to note Dickens' solutions to the dilemmas faced by his moral character, Pip. Aristotle asserted that the form of fiction demanded of every work that the protagonist begin with a place in the social world; some action in the plot lead to a disruption of this order, the protagonist losing his rightful position. The classic definition then went on to name a 'comedy' a piece in which the hero at the end of the work successfully re-integrates into the world of man; 'tragedy,' conversely, refers to literature in which the hero is in some way barred from the world in which he once played a part. If one were to judge Great Expectations by these standards, the play contains elements both of comedy and tragedy, because Pip exists as a character of many detached worlds. It is possible to find five complete and discrete societies in the England of Dickens' novel; these five summarize the whole of the transitional period known to postmodern critics as 'Victorian.' The two representatives of the old world's feudal order, are those of village labor (Joe and Biddy) and aristocracy (Mrs. Havisham and Estella); of the new world one sees the urban poor (Jaggers' clientele and Pip's 'Avenger ), the working class (Jaggers and Wemmick), and the entrepreneurs/capitalists(Compeyson and Pumblechook). Pip in his time samples all five circles, belonging variously to each over the course of the novel, making it very difficult to assess his 'reintegration into society' at the end it is certainly impossible (and almost certainly undesirable) that he should become integrated into them all, so he must choose his one path; Dickens leaves to his readers evaluation of Pip's success. The world of Joe Gargery, Mrs. Joe, and Biddy is certainly the most personal, sincere, and touching of settings presented in the novel. Clearly the novelist meant it to be representative of pre-industrial, 'village' labor. Joe's occupation (blacksmith) and his thoroughly eighteenthcentury residence in the rural 'marsh country' of Sussex are indicative of this. But Dickens endows these characters with what Tolstoy calls 'simple peasant virtues ; honest toil instills in his men such as Joe a sincerity of feeling, and somehow forms men of decency, integrity, and principle (Pip). Miss Havisham, on the other hand, stands a representative of feudal aristocracy;though her family money in fact was made on the brewery adjacent to Satis House(suggestive of capitalism), her bearing and lifestyle suggest very strongly aristocratic flavor. Pip's language describing Satis House in many ways denote its 'castleness' (Calder, 84 87). And Pip himself in remembering his first entrance to her room speaks of her as a 'fine lady' (Calder, 87). In sharp contrast to this rural civilization lies the town, with completely different characters and conflicts. Dickens' oppressors here are clearly not of the same level as Mrs. Havisham: the Pumblechooks, Compeysons, and Drummles are neither majestic nor intimidating figures in themselves. But in no way does Dickens make them likable, either. Their businesses are founded upon the toil of workers, and in some way Dickens makes it clear that the relationship between capitalist and subordinate is a parasitic one. Pumblechook is a hypocrite of the worst sort, a bumbler with too-real economic dominion over the working class. For example, Mrs. Joe wants desperately to impress Pumblechook solely to win his favor, so desperately she misses Christmas Mass in order to finish preparations for a dinner in his honor. Pip is inevitably unable to impress such a man, however, because he represents no capital (the only subject of interest to the man). When the young gentleman comes into his inheritance, Pumblechook assumes a complete attitude reversal; Pip, because he has money, is now a man the capitalist deems worthy of respect. It is the entrepreneurs of the novel whom, for the most part, Dickens blames for the abject poverty, decadence, and criminal malevolence of those at Smithfield and Newgate. The riffraff of London, at least, respect Jaggers for his competence; Dickens endows his lower classes with keen acuity, discernment of capability far greater than that of the those who actually wield economic power. Dickens' men of station are, without exception, either irretrievably stupid (Drummle) or entirely corrupt (Compeyson). Dickens seems to find the greatest virtue in London's working class, the lower middle class: the Herbert Pockets, Jaggerses and Wemmicks. Though (inevitably) there is much for the novelist to criticize in their values and mannerisms, these characters tower as prominent examples of the most virtuous of the London crowd. These men do not actually own great wealth or possess political or economic stature, but instead serve as the actual achievers, those who get work done. Dickens' middle class possesses almost schizophrenic dichotomies of character. Its rational half cherishes and treasures a very detached and reserved, 'rational' manner, which Jaggers and Wemmick epitomize; Jaggers' extreme disinclination to recommend anyone or anything, his disdain of emotion or 'unbusinesslike airs , and his late-revealed support of the helpless (evidenced in his support of Molly, Estella's mother, after her breakdown) serve to make him an exceedingly multifaceted character. Wemmick is very much the same, and even a better example: the dual character of the clerk mystifies Pip at first. This is perhaps best evidenced in Chapter 48, when Jaggers, Wemmick, and Pip dine together. In front of Jaggers, Wemmick assumes a tacit, efficient but impersonal manner: 'Wemmick drew his wine when it came round, quite as a matter of business that came round just as he might have drawn his salary when and with his eyes on his chief, sat in a state of perpetual readiness for cross-examination.' (404). Pip, bewildered, supposes himself to have dined somehow with Wemmick's ' wrong twin all the time only externally like the Wemmick of Walworth.' (404). Pip's bewilderment is compounded by the suddenness of Wemmick's malleability: ' we had not gone half a dozen yards down Gerrard-street in the Walworth direction before I found that I was walking arm-in-arm with the right twin, and that the wrong twin had evaporated into the evening air.' (Calder, 404). Wemmick discusses 'portable property' with the utmost pragmatism and respect, while simultaneously living in his 'castle' of knickknacks, gadgets and toys which cherish the human spirit Dickens summons from his readers a remarkable pathos for London's lower classes. In Chapter 20, Pip recounts Jaggers' encounter on the street with several of his clients. Disreputable, transparently villainous, these pitiable characters nevertheless evoke from Dickens' readers a feeling of sympathy. Part of this identification the reader feels for them lies in the fact that they are clearly capable human beings; their tragedy lies simply in the fact that the Victorian work ethic allows no sympathy for 'unsuccessful' men in society; in some way it is they, and not industrial capitalism, who are felt to be at fault for their position. The author of Great Expectations, it may be said, disagrees. Clearly it is London's economic structure which makes them what they are; the novelist hopes to make clear to his readers that the miserable are not guilty in any way of choosing their present social station. But never are they cast as good or virtuous, either. It is easy to see, in conclusion, why Dickens felt his novel to be a 'tragi-comedy' (24). Poor Pip yearns to be a member of his rural, working world, but finds he cannot because it ignores the realities of the modern world and has no notions of 'higher things.' He would like to be genteel like Miss Havisham and Estella, but finds himself incapable of their aristocratic coldness. Similarly his depth of understanding and compassion forbid his becoming a capitalist. None of the urban lower class choose their position, and it has little if any appeal to Pip. But he also finds himself somewhat disturbed by the unreconciled double-sidedness, sort of unconscious division common to his friends of the working class. The novel ends a tragedy according to classical definitions, because Pip ends unreconciled to any of his options, an aloof, solitary bachelor. To be sure he obtains work with Clarriker and Co. and his comrade Herbert, visits Joe and Biddy and 'young Pip,' and comes to an understanding with Estella, but he is somehow in a greater sense, alone. Works Cited: Charles Dickens. Great Expectations. Angus Calder, ed. Middlesex, England: Penguin Books, 1965.