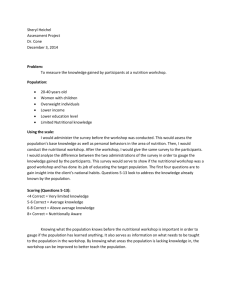

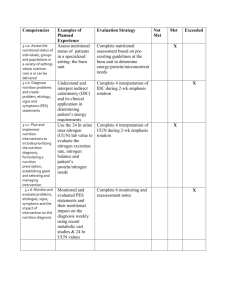

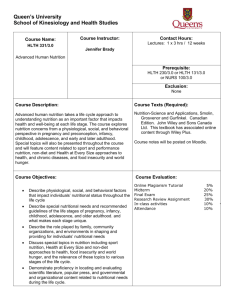

Nutrition- A Guide to Data Collection, Analysis, Interpretation

advertisement