Full Text - BioTechniques

advertisement

From the Editor

A Positive Need for Negative Data

Douglas McCormick

Editorial Director, BioTechniques

How much better might science fare if we habitually shared

our misses along with our hits?

F

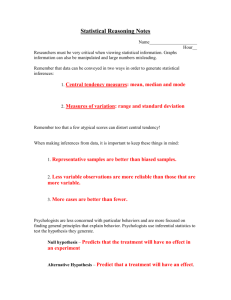

or years, we’ve toyed with the idea of starting a Journal of

Null Results (JNR). Back in 2002, we got as far as registering

nullresults.com and designing a logo: an empty pair of

brackets denoting the null set. Does science need such a journal?

If needed, could it work?

This ambition is not—or not merely—a desire to found an

empire on the failures of others. (Think of it, though: every

grant application and thesis proposal

and paper would have to document a

search of JNR.)

{}

Officer at SmithKline Beecham), he was dubious about the scheme,

which he called (as far as memory serves) intellectually attractive

but fraught with practical difficulties. Experiments “work” when

hypothesis, experimental design, detailed method, materials, and

execution all align. If any of these elements fail, however, the

experiment fails. It can be exceedingly difficult to tell whether the

data actually support the null hypothesis—rather than revealing,

say, contaminated reagents, sloppy technique, or poor design.

Couple that with most researchers’ reluctance to publicly air what

they consider mistakes, and with the difficulty of finding reviewers

canny enough to separate the null-result wheat from the illexecuted chaff, and you wind up with some significant doubts

about the workability of the project.

A Modest Literature

The idea of publishing negative data is not original with us.

Social scientists founded the Journal of Spurious Correlations

(www.jspurc.org) in 2005. The Journal of Articles in Support

of the Null Hypothesis (www.jasnh.com,

for psychologists), and the Journal

of Null Results in Biomedicine

(www.jnrbm.com) both started in 2002.

And Johns Hopkins pathologist Scott E.

Kern, M.D., founded the grandfather of

the genre, NOGO: the Journal of Negative Observations in Genetic

Oncology (www.path.jhu.edu/NOGO) in 1997.

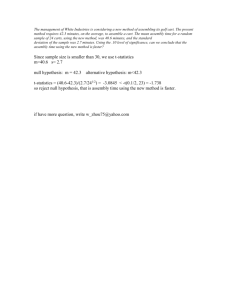

The Journal of

Null Results

One of the first things we’re told in

science is, “There’s no such thing as a

failed experiment. Every piece of data teaches you something.”

One of the greatest experiments in scientific history, Michelson’s

and Morley’s attempt to detect the effects of the luminiferous

ether on light transmission, produced a null result. We quickly

learn, however, that it’s very difficult to build a curriculum vitae

out of negative data.

Happenstance

This is a profound cultural error, however. Consider 1000 research

coinflipologists, each conducting an experiment of 10 coin tosses.

Chances are that two or three of these experiments will come

up heads at least nine times out of ten. The three preeminent

coin-flippers then publish their data. The 997 “unsuccessful” coinflippers can’t get a paper through review. As far as the literature is

concerned, flipped coins tend to come down heads.

None of these efforts has more than scratched the surface of

negative results, though. The Journal of Null Results in Biomedicine

had published just eight articles through the first 8 months of

2007. NOGO’s latest entry is dated 2006.

We talked to Professor Kern briefly at the beginning of

September. He has indeed found most scientists reluctant

to share negative data, which helps other laboratories while

not materially advancing their own reputations. This, he says,

reflects badly on scientists in general.

Consider, too, the baneful effects of a very good hypothesis that

happens to be incorrect. It will occur over and over again to bright

researchers. These scientists will search the literature and then,

finding nothing on their new hypotheses, pursue programs of

experiments. Think how much time, energy, and creativity could be

constructively re-channeled if all of the negative data were available.

He remains concerned about the reporting of negative results

and increasingly dismayed by the proliferation of negative results

masquerading as significant findings. He does note, however, that at

least one countervailing trend in his own field of cancer genetics is

having a positive impact on negative data: large-scale sequencing,

with the data deposited wholesale in vast databases, record the

negative data along with the positive. “If you sequence 13,000 genes,

and only about 1,300 of them show mutations, then the other 11,700

sequences deposited are essentially null results.”

So a comprehensive index of negative results seems like a good

idea…maybe. A decade ago, when we put the idea to George Poste

(now head of the Arizona Biodesign Institute, then Chief Technology

Is that, then, the solution? Not a journal but an online registry,

chronicling not failure but new successes in defining the frontiers

of discovery?

Vol. 43 ı No. 4 ı 2007

www.biotechniques.com ı BioTechniques 389