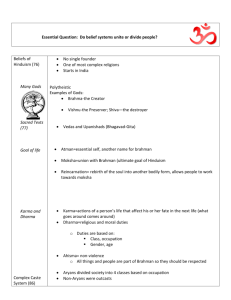

Kinship Institutions and Sex Ratios in India

advertisement