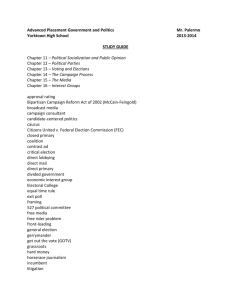

Campaign Finance Reform and Disclosure

advertisement