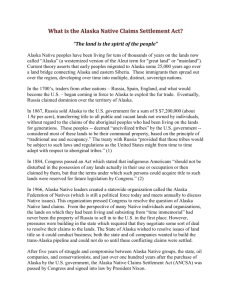

The Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act at 35

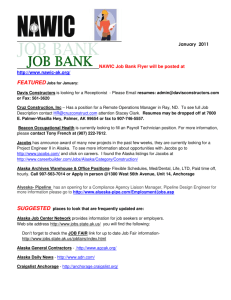

advertisement