Foreign Direct and Portfolio Investments in the World

Foreign Direct and Portfolio Investments in the World

Masaya Sakuragawa

∗

and Yoshitsugu Watanabe

∗∗

Abstract

This paper investigates the determinants of foreign direct and equity portfolio investments by using panel data on 75 countries, covering OECD and emerging market countries. Financial development affects capital flows by type in different ways. Credit market development has a positive effect on attracting FDI in emerging market countries, while it has a positive effect on attracting equity portfolio investment in OECD countries. The threshold level of financial development for attracting portfolio flows is higher than the one for attracting FDI. In addition, capital account liberalization has a positive effect on attracting FDI, but an effect on flowing out equity portfolio investment in emerging market countries.

Key Words: Globalization, Capital Account Liberalization, Financial Market Development

JEL Classification Codes: F21, F36, O16

∗

Keio University. E-mail:masaya22@gmail.com

∗∗

The Global Security Research Institute of Keio University.

1

1.

Introduction

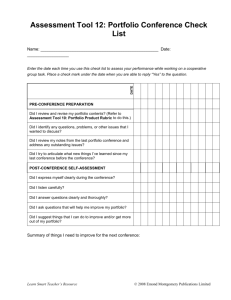

In this decade, international capital flows, especially portfolio investment flows, increase rapidly along with advances in globalization of the economy. Figure 1 represents changes in the net financial account as a percentage of the world nominal GDP. This figure indicates growing trend of capital inflows.

Are expansions of international capital flows beneficial? In principle, developing countries can encourage economic growth through attracting capital flows from foreign countries. But in practice, there is a possibility that capital flight causes economic fluctuation and financial crisis.

Lessons of historical experience suggest that it is important to stably attracting capital flows into host countries to make financial globalization beneficial.

Moreover, does the composition of capital flows matter? Debt flows appear to be more volatile than other types of flows and easily reversible in times of crises. In contrast, equity-related flows are supposed to be more stable and less prone top reversals. In addition,

FDI is believed to bring with them transfers of technology and managerial expertise. Hence, the outbreak of Asian crisis should have invoked emerging countries to change the composition from debt to equity-related flows.

The evidence is, however, at odds from this prediction. Figure 2 and Figure 3 depict net FDI and portfolio inflows, as a percentage of GDP, respectively. Since the period around the Asian crisis, the net FDI inflow to emerging market countries is increasing, while the net portfolio inflows are declining and negative since around 2000. Figure 4 and Figure 5 document net equity portfolio investment and net debt portfolio investment as a percentage of GDP respectively. We observe the sharp reversal of capital inflows into emerging market countries not only debt but also equity portfolio investment after Asian crisis. These facts suggest that emerging countries change the composition of capital flows from portfolio investment to FDI. A central question is why the remarkable change in the composition of equity flows arose over this decade.

To answering this question, we investigate the determinants of FDI and equity portfolio flows by using the generalized method of moments (GMM) estimators developed for dynamic models of panel data that were introduced by Arellano and Bond (1991) and Blundell and Bond

(1998). In particular, we aim to identify common determinants of FDI and portfolio flows, specific determinants for each type of flow, and factors that may have opposite effects on the two types of capital flows.

We show that the domestic credit market development is an important factor in attracting equity-related capital flows and has a different threshold effect. As for FDI, the domestic credit market development has a positive effect solely on emerging market countries, but as for equity portfolio investment, it has a positive impact rather on OECD countries. One possible

2

explanation to reconcile these findings is that there are different threshold of financial development above which capital begin to flow in, which is suggestive of the notion that FDI is the type of foreign investment that realizes smaller agency costs of corporate finance than portfolio flows. These results imply that the financial development affect capital flows by type in different ways, depending on the degree of its development. More sophisticated domestic credit market is needed to attract equity portfolio investment which have relatively high agency cost.

In addition, we find that capital account liberalization has an effect on attracting foreign direct investment but an effect on flowing out equity portfolio investment in developing countries. These effects are not observed in developed countries. These results imply that capital account liberalization does not necessarily bring about desirable results.

The rest of the paper is organized as follows. Section 2 provides a brief overview of the relevant theoretical and empirical considerations. Section 3 discusses the determinants of capital flows and the econometric methodology. Section 4 presents the empirical findings. Section 5 concludes.

2.

The Determinants of International Capital Flows: A Review of Literature

Much literature suggests that capital flows are determined by a variety of macroeconomic and institutional factors. In addition to these factors, the recent literature investigates sensitivity of capital flows to country’s openness and domestic financial market development.

2.1.

Theoretical Analysis about Sources of Capital Movement

The income level is supposed to be a most important determinant of capital flows. The standard neoclassical theory predicts that capital should flow from rich to poor countries. Under the usual assumptions of countries producing the same goods with the same constant returns to scale production technology using capital and labor as factors of production, differences in income per capital reflect differences in capital per capita. Thus, if capital were allowed to flow freely, new investments would occur only in the poorer economy, and this would continue to be true until the return to investments were equalized in all countries.

However, Lucas (1990) compares the U.S. and India in 1988 and demonstrates that, if the neoclassical model were true, the marginal product of capital in India should be about 58 times larger than that of the U.S. In face of such return differentials, all capital should flow from the

U.S. to India. But, in practice, we do not observe such flows (“Lucas Paradox”). Lucas questions the validity of the assumptions that give rise to these differences in the marginal product of capital and asks what assumptions should replace these. He shows if we include the

3

accumulation of human capital in the standard neoclassical theory, the “Paradox” disappears in theoretically. After his work, many researchers have analyzed international capital flows focusing on the difference in fundamentals that affect the production structure of the economy, such as technological differences, missing factors of production, government policies, and the institutional structure.

On the other hand, there is much literature explaining international capital flows focusing on international capital market imperfections, mainly asymmetric information. Although capital has a high return in developing countries, it does not go there because of the market failures. For example, Gertler and Rogoff (1990) tried to resolve the perverse capital mobility based on the information-theoretic approach. They showed that in a two-period model capital does not necessarily flow from the capital-rich North to the capital poor South but may move in the reverse direction when asymmetric information that exists between international lender and borrower creates a moral hazard problem. Boyd and Smith (1997) analyze a model of international lending and borrowing in the presence of the costly-state-verification problem, demonstrating that the combination of capital market imperfections and endogeneity in borrowers’ wealth can lead to multiple steady states in a world economy with an integrated capital market. They show that in countries with high capital stocks (and income level), more internal financing will be provided than is the case in countries with low capital stocks. As a result, countries with relatively high capital stocks will be attractive places to invest, and such countries will be net recipients of external capital investment.

The analytical frameworks based on the presence of asymmetric information apply to probe the influences of various factors, such as exchange rate and international capital market integration, on international capital flows. Froot and Stein (1991) investigated the effect of exchange rate on international capital flows in the presence of imperfect capital markets. They present an imperfect capital market story for why a currency appreciation may actually increase foreign investment by a firm. Imperfect capital markets mean that the internal cost of capital is lower than borrowing from external sources. Thus, an appreciation of the currency leads to increased firm wealth and provides the firm with greater low-cost funds to invest relative to the counterpart firms in the foreign country that experience the devaluation of their currency. This has an empirical implication that currency depreciation cause capital outflow.

Sakuragawa and Hamada (2001) analyzed international capital mobility and the effect of international capital market integration in the environment that the North (i.e., rich countries) has as superior information structure to the South (i.e., poor countries). They show that the capital market integration does not necessarily lead to the welfare improvement of the South because the flight of capital from the South to the North can drive the South into a poverty trap.

In liberalizing the capital market, governments of developing countries should take the

4

importance of the timing of the liberalization into account and should not necessarily accept the advice of developed countries that tempt them to lift capital control. Borrowers’ moral hazard on investment allocation between the verifiable profit and the unverifiable one can be a source of capital outflows if the capital account is opened. Capital flight can be interpreted as a rational response to asymmetric information that exists between lenders and borrowers.

In recent works, the determinants of the composition of international capital flows have been analyzed based on the information-theoretic approach. According these analyses, the feature that most distinguishes FDI from other capital inflows is the degree of control over management. Because increased control may alleviate the adverse consequences of asymmetric information and poor investors’ rights, investors may prefer FDI over portfolio investment.

1

2.2.

Empirical findings about the determinants of capital flows

The principal difference between FDI and portfolio investments is the extent of control. For statistical purposes, governments and international organizations may require a minimum level of ownership for an investment to be treated as FDI. The OECD and IMF take FDI to be foreign investment in which ownership is more than ten percent of the voting securities of the company.

The foreign investment in which ownership is under ten percent is identified as portfolio investment. The degree of separation of ownership from management is a decisive factor differentiating both investments.

This difference is crucially important from the viewpoint of asymmetric information aspects.

Information disparity between managers and owners (foreign investors) in FDI is narrower than equity portfolio investment because in FDI foreign investors directly implicate the management of invested corporation. In this sense, portfolio investment has relatively high agency cost. In this subsection we mentioned empirical findings about the determinants of each type of capital flows.

2.2.1.

Foreign Direct Investment

Most empirical works which investigate the determinants of capital flows focus on FDI based on the pull and push approach, which distinguishes between domestic factors (pull factors) and external factors (push factors) and tries to bring together the various investment considerations. Recent surveys of the empirical literature suggest that some variables, for example a country’s economic fundamentals, financial market imperfections, the openness of

1

Albuquerque (2003) attempted to answer the question why FDI is less volatile than other financial flow by using a model under the assumptions of imperfect enforcement of financial contracts and inalienability of FDI and finds that the high volatility and low persistence of non-FDI capital flows to developing economies simply reflect the optimal responses of inter national investors to change in default risk.

5

the host market, and the institutional environment, play a key role in the country’s ability to attract FDI (Blonigen (2005), Faisal et al. (2005)).

The theoretical considerations described above suggest that capital flows are determined by the country’s economic fundamentals. In previous literature, income level, human capital, exchange rate volatility, and other variables are considered as economic fundamentals (e.g.

Alfaro et al. (2008)).

2

The theoretical consideration described above also suggests that the imperfection of financial markets is an important determinant of capital flows. The deeper a country’s financial markets, the more capital flows the country attracts. For FDI, deeper financial markets may allow foreign firms to finance short- and long-term transactions more easily and meet capital needs in the local market (Alfaro et al. (2008)). Many works use domestic financial market development variables as a proxy for financial market imperfections.

The hypothesized link between FDI and the openness of the host country’s market is seen as fairly clear by trade literature; higher trade protection should make firms more likely to substitute affiliate production for exports to avoid the costs of trade, so that more trade restrictions could also lead to more FDI outflows if firms wanted to serve the local market and hence wanted to bypass existing trade restrictions through FDI. Moreover, foreign investors are often interested not only in serving the local market, but also in pursuing export-oriented activities. They are, therefore, likely to favor countries with highly opened traded goods sector.

2.2.2.

Portfolio Investment

Unlike the voluminous literature on the determinants of FDI inflows, research on the determinants of portfolio inflows is limited. Some variables are thought as common determinants of FDI and portfolio flows. For example, the rate of return on investment in host countries is one of the most important pull factors of portfolio investment as well as FDI. Other common factors are domestic financial development and capital controls. As mentioned above, domestic financial market development represents the degree of financial market imperfections.

However, the existing empirical evidence is mixed. Alfaro et al. (2008) reported that capital controls have a negative impact on average inflows of direct and portfolio equity investments, but financial market development does not have definitive effects. Montiel and Reinhart (1999) investigated the influence of capital controls on the volume and composition of capital flows, and present evidence that capital controls influence the composition of flows, not the volume.

2

Alfaro et al.(2008) investigated the role of the different theoretical explanations for the lack of lows of capital from rich to poor countries in a systematic empirical framework and show that during 1970-2000, low institutional quality is the leading explanation. Froot and Stein (1991) provided empirical evidence of increased inward FDI with currency depreciation through simple regressions using a small number of annual US aggregate FDI observations.

6

3.

Empirical Analyses

We examine what factors determine each type of capital flows using the ordinary least squared (OLS) estimators and the generalized method of moments (GMM) estimators developed for dynamic models of panel data that were introduced by Arellano and Bond (1991) and Blundell and Bond (1998). Our sample comprises annual data from 1988 to 2005 for up to

74 countries: 16 African countries, 16 Asian countries, 20 European countries, 16 South and

North American countries, and 7 other countries. According to agency theory, the determinants of capital flow may differ from developed and developing countries, so that we estimate based on two types of dataset; OECD countries and emerging market countries.

3.1.

The empirical specification

Based on these arguments, we estimate the following equation; y it y it

−

1

+ β ′ FUND it

+ γ ′ OPEN it

+ δ ′ FD it

η ε it

(1) where y it

represents the ratio of net flows of capital to GDP. As dependent variables, we consider two types of equity-related capital flows, FDI and equity portfolio investment;

FUND it

is a vector of macroeconomic fundamental variables; OPEN it

is a vector of measures of goods and financial market openness; FD it

is a vector of measures of financial development;

η i

is an unobserved country-specific effect;

ε it

is the error term; and the subscripts i and t represent country and time period, respectively.

Recent works have shown that international capital flows tend to cluster in particular locations (“agglomeration” effect).

3

More specifically, international capital flows depend on own and neighboring countries’ stock of international capital; that is, countries that have been successful in attracting capital flows from foreign countries in the past are more likely to do so in the future. This specification with a lagged dependent variable allows us to capture agglomeration effect. It also allows us to correct for residual autocorrelation present in static panel specification. This model specification assumes that country-specific unobservable characteristics, such as norms and cultural differences, are invariant over time and it assumes slope homogeneity across counties.

A vector of economic fundamental variables ( FUND it

) includes the income level, the human capital level, and exchange rate volatility of each country. As for the income level, we

3

For example, Coughlin and Segev (2000) estimated that FDI into neighboring provinces increase FDI into a Chinese province and assign this as evidence of agglomeration effect.

7

use log of GNI per capita ( LGNI it

).

4

The income level is one of the most important variables to determine capital flows. If capital flows from rich to poor countries, the coefficient of LGNI it is expected to be negative. In contrast, if capital flows out from poor countries as the agency theory suggests, the coefficient is expected to be positive. As for the human capital variable, we use the average schooling years in the total population ( HC it

). The high level of education will reflect highly-educated workers. So the coefficient of HC it

is expected to be positive. As for the exchange rate volatility variables, we use the annual standard deviation of monthly changes in the real effective exchange rate ( ERV it

). Exchange rate volatility increases the uncertainty of demand for products of export-oriented firms and may reduce the profitability of FDI. It is, therefore, expected to have an adverse impact on FDI. However, an impact on portfolio flows is less clear. Since portfolio investors with a short investment horizon may be able to hedge currency risk easily, exchange rate volatility should have little impact on portfolio investment.

A vector of market openness variables ( OPEN it

) includes goods and financial market openness of each country. Following previous empirical works, we use the ratio of imports plus exports to GDP as a proxy for goods market openness GOPEN it

. In the case of FDI, the coefficient of GOPEN it

will be positive. In contrast, the effect of trade openness on portfolio flows is less clear and mixed.

For financial market openness variable, we use capital account openness index ( KAOPEN it

) developed by Chinn and Ito (2002).

5

This measure tends to be larger as capital markets are more liberalized. So as for FDI, the coefficient of KAOPEN it

will be positive.

For financial development variables ( FD it

), we consider two measures of market development: First, we consider the credit market development. Working capital will be typically financed by the bank in the host country so that the development of the banking system of the host country is important. We use domestic credit to the private sector ( DC it

) as percentage of GDP as the proxy for domestic credit market development. Second, we consider equity market development. We use the domestic stock market capitalization of listed companies ( SMC it

) as percentage of GDP as the proxy for stock market development. The deeper country’s financial markets, the more capital flows country attracts. In particular, well-developed financial markets appear to be a precondition for portfolio inflows, so that we expect a positive relationship between financial development and capital flows.

4

Data definition and sources are described in Table 5.

5

This index is the first standardized principle component of variable indicating the presence of multiple exchange rates, variable indicating restrictions on current account transactions, variable indicating the requirement of the surrender of export proceeds, and the share of a 5-year window that capital controls were not in effect.

8

3.2.

Econometric Methodology

In this paper, we adopt two estimation methods. First, we simply estimate Eq. (1) using ordinary least squares (OLS) with White’s robust standard errors. However, if a lagged dependent variable is included in the estimation, OLS estimates are known to be biased and inconsistent. Strictly speaking, problem in applying OLS to Eq. (1) is that lagged dependent variable ( y it

−

1

) is endogenous to the fixed effects, which gives rise to “dynamic panel bias”

(Anderson and Hsiao (1981)). Moreover, as much literature pointed out, capital flows and income level are closely related during the same period, so that LGNI may be an endogenous variable to the regression.

To deal with this endogeneity problem, we use the generalized method of moments (GMM) estimators developed for dynamic models of panel data that were introduced by Arellano and

Bond (1991) and Blundell and Bond (1998). First, to eliminate the country-specific effect, we take first-difference of Eq. (1),

Δ y it

= ρΔ y it

−

1

+ β ′ Δ FUND it

+ γ ′ Δ OPEN it

+ δ ′ Δ FD it

+ Δε it

(2)

Then we must have to choose valid instruments to deal with the endogeneity problem thata rises from the fact that the new error term.

Δ

ε

it

is correlated with the lagged dependent variable,

Δ y it

−

1

and the likely endogeneity of the other explanatory variables. The way our panel estimator controls for endogeneity is by using “internal instruments”, that is, instruments based on lagged value of the explanatory variables. Under the assumptions that (a) the error term

ε it is not serially correlated, and (b) the explanatory variables X it

=

( it

, it

, it

) are endogenous, the GMM dynamic panel estimator uses the following moment conditions; it s

( ε it

− ε it

−

1

)

=

0 for s

≥

2; t

=

T (3)

E

X it s

( ε it

− ε it

−

1

)

=

0 for s

≥

2; t

=

T (4)

Eq. (3) means that y it

−

2

and deeper lags dependent variable become a candidate of valid instrumental variables for

X it

−

2

Δ y it

−

1

in Eq. (2). Likewise, Eq. (4) means that if

and deeper lags are available as instruments for

X it

is endogenous,

Δ X it

. We refer to the GMM estimator based on Eqs.(3) and (4) as the difference GMM estimators.

6

6

If X it is predetermined variables (i.e., the explanatory variables are assumed to be uncorrelated with future realizations of the error term), the moment condition in Eq. (4) is

9

There are, however, conceptual and statistical shortcomings with this difference estimator.

Blundell and Bond (1998) showed that when the explanatory variables are persistent over time, lagged levels of these variables are weak instruments for the estimate equation in differences.

Instrument weakness influences the asymptotic and small-sample performance of the difference estimator. Asymptotically, the variance of the coefficients rises. In small samples, Monte Carlo experiments show that the weakness of the instruments can produce biased coefficients.

To reduce the potential biased and imprecision associated with the usual difference estimator; we use a new estimator that combines in a system the regression in differences with the regression in levels (Blundell and Bond (1998)). The instruments for the regression in differences are the same as above. The instruments for the regression in levels are the lagged differences of the corresponding variables. These are appropriate instruments under the following additional assumptions:

⎣

η ⎤ =

E y

η =

0 for all p and q ,

E X η ⎤ =

E

⎡ X η =

0 for all p and q .

These equations mean that lagged dependent variable and other explanatory variables correlated with the country-specific effect but those correlations are time-invariant. If this assumption holds, although there may be correlation between the levels of the right-hand side variables and the country-specific effect in Eq. (1), there is no correlation between the differences of these variables and the country-specific effect.

The additional moment conditions for the second part of the system (the regression in levels) are

E ⎣

( y

− y it s 1

)( it

)

=

0 for s

=

1, (5) replaced to

E

[

X

(

ε it

− ε it

−

1

)

]

=

0 for s

≥

1; t

=

T

.

This equation means that if instruments for

X it

is predetermined, X it

−

1

and deeper lags are available as

Δ X it

in Eq. (2). Further, if X it is strictly exogenous variables, all X it

are available as instruments for Eq. (1) and Eq. (2).In this paper, we instrument strictly exogenous variables with themselves following Arellano and Bond (1991). In the case X it

include a combination of endogenous, predetermined and strictly exogenous variables, we can apply

GMM technique to estimate parameters in Eq.(2) with choosing instruments and imposing moment conditions appropriately.

10

E

(

X − X it s 1

)( it

)

=

0 for s

=

1, (6)

Thus, we use the moment conditions presented in Eqs. (3), (4), (5), and (6) and employ a GMM procedure to generate consistent and efficient parameter estimates. More precisely, we think that

Δ y it

−

1

and

Δ

LGNI it

are correlated with

Δ

ε

it

in Eq. (2), and instrument for their own level variables with two and three lags

7

. We refer to the GMM estimator based on these conditions as the system GMM (SGMM) estimator.

There are two versions in the system or difference GMM estimator depending on the choice of the weighting matrix like as usual GMM, one-step and two-step procedures. In large sample, two-step system or difference GMM is theoretically more efficient asymptotically than one-step one. However, in small sample, two-step estimator produces standard errors that are downward biased when the number of is large severely enough to make two-step GMM useless for inference (Arellano and Bond (1991), Roodman (2006)). Taking into account this problem, we use a small-sample corrected two-step standard error proposed by Windmeijer (2005)

8

.

4.

Estimation Results

4.1.

Descriptive Statistics

Table 1 provides descriptive statistics during 1985- 2005. Comparisons of figures between

OECD and emerging market countries are worthy of comments. Average net inflows of FDI over GDP have a mean of 0.0005 in OECD countries and a mean of 0.016 in emerging market countries. Net FDI inflows are on average greater into emerging market countries than into

OECD countries. On the other hand, average net inflows of equity portfolio investment over

GDP have a mean of -0.0039 in OECD and a mean of -0.0047 in emerging market countries.

Net equity portfolio investment outflows from emerging market countries over GDP are larger than from OECD countries on average.

Average income per capita and average human capital in OECD countries are larger than in

7

In moment conditions Eqs.(3) and (4), we can use four or deeper lags of y and LGNI as instrument variables if these candidates correlate with Δ y it

−

1

and Δ

LGNI it

. However, the correlation may be weak and invalid. Hence, we use only two and three lags variables as instruments. Our estimation results do not depend on the number of lags in instrument variables because the results are qualitatively similar when deeper lags variables are used for instruments.

8

Windmeijer (2005) found that in difference GMM regressions on simulated panels the two-step efficient GMM performs somewhat better than one-step in estimating coefficients, with lower bias and standard errors. And the reported two-step standard errors, with his correction, are quite accurate, so that two-step estimation with corrected errors seems modestly superior to robust one-step.

11

emerging market countries. OECD countries have highly developed domestic financial market which is measured by domestic credit to private sector and stock market capitalization. One exception is goods market openness measured by exports plus import over GDP. This measure is used as a proxy for goods market openness in much literature and become large if goods market more open. Although OECD countries intuitively may have highly-opened market than emerging market countries, average goods market openness in Table1 has inverse magnitude relation. One possible explanation to reconcile this magnitude relation is that this measure essentially represents the importance of foreign trade to domestic economy. In ordinary, the degree of dependence on foreign trade may be higher in emerging market countries, so that there is a possibility that this measure capture not only goods market openness but also the degree of dependence on foreign trade.

4.2.

Estimation Results for FDI

Table 2-1 and Table 2-2 present the estimation results for FDI to OECD countries data and emerging market countries data, respectively. We estimate four types of model; first type, which corresponds to regression (i) and (v), is the most simple estimation; second type, which corresponds to regression (ii) and (vi), include dummy variables controlling for special factors; third type, which corresponds to regression (iii) and (vii), include exchange rate volatility variable (ERV) but not control for special factors; fourth type , which corresponds to regression

(iv) and (viii), include all variables. The first four results o regressions (i-iv) are based on OLS estimation; the last four results (v-viii) use the system GMM technique.

We also report the “Hansen test”, where the null hypothesis is that the instrumental variables are uncorrelated with the residual and the “Arellano-Bond test”, where the null hypothesis is that the error in the differenced equation exhibits no second-order serial correlation.

9

The SGMM regressions in Tables 2-1 and Table 2-2 satisfy the specification test.

There is no evidence of second order serial correlation and regressions pass the Hansen specification test.

In Table 2-1, lagged dependent variable is positive and significant at 1% significant level in

OLS but not in system GMM. As mentioned above, y it

−

1

is endogenous to fixed effects in the error term, so that OLS estimator of

ρ

in Eq. (1) has dynamic panel bias. In this sense, we could not have any definitive evidence of the agglomeration effect in OECD countries.

The three economic fundamental variables (LGNI, HC and ERV) have expected signs but not insignificant with some exception. LGNI is negative and significant at 1% significant level

9

Due to the Arellano-Bond difference GMM formulation, new residual (which is first differences of the original model residual) should be autocorrelated of order 1 but not autocorrelated of order 2 if the model is well specified.

12

in OLS but not in system GMM. The endogeneity of LGNI might give rise to these conflicting results. This result implies that FDI do not flow from relatively-rich to relatively-poor among

OECD countries. GOPEN is positive but only significant at 10% level in three out of eight equations. KAOPEN is also insignificant except for one case. We could not obtain evidence that the promotion of market liberalization attract FDI inflows.

One controversial finding is about stock market development. SMC is negative and significant in all cases, which seems be opposite to our expectation. Although the interpretation of this result is complex and controversial, one possible explanation is that countries with well-developed stock market have high availability and familiarity of finance based on the arm’s length principle like as merger and acquisition FDI, so that these countries actively increase foreign direct investment outwardly.

Turning now to Table 2-2, the coefficient of lagged dependent variable is positive and significant at 1% significant level in every case, so that we confirm an agglomeration effect clearly. In addition, financial market openness (KAOPEN) and domestic credit market development (DC) are positive and significant in many cases. These findings imply that FDI flows into emerging market countries with open financial market and developed banking system.

On the other hand, three economic fundamental variables (LGNI, HC and ERV) and goods market openness (GOPEN) have the mixed sign and are insignificant in almost all equations.

When we comprehensively evaluate the results in Table 2-1 and Table 2-2, several interesting aspects of the determinants of FDI are revealed. First, there is a threshold of domestic credit market development attracting FDI inflows. The domestic credit market development is positive and significant in emerging market. As seen in Table1, emerging market countries have weak domestic financial market relative to OECD countries. This result suggests that emerging market countries are subject to credit constraints to finance their projects and investors who make FDI in these countries prefer to the countries with well-developed credit market alleviating credit constraints caused by asymmetric information.

Second, the effect of financial market integration on net FDI is positive and significant in emerging market but not in OECD, so that the effect is not symmetric between OECD and emerging market countries. As seen in Table1, OECD countries have accelerated financial liberalization compared to emerging market countries on average. This result may reflect that

OECD countries have fully liberalized financial market and have already attained a certain threshold of market liberalization which has a positive effect on capital flows.

4.3.

Estimation Results for Equity Portfolio Investment

Table 3-1 and Table 3-2 present the estimation results for equity portfolio investment to

OECD and emerging market countries, respectively. The SGMM regressions in two tables

13

satisfy the specification test. There is no definitive evidence of second order serial correlation and regressions pass the Hansen specification test.

In Table 3-1, LGNI is negative and significant at 1% significant level in all estimations.

This result implies that equity portfolio investment flow from relatively-rich to relatively-poor

OECD countries as standard theory suggested.

Notable findings are about the effects of financial market liberalizations and the development of domestic credit market. KAOPEN has positive but insignificant with one exception. This result implies that at least, there is no evidence that financial market integration cause capital flight from OECD countries. Also, DC has much importance on capital flows in

OECD countries. DC has positive and significant at 1% significant level in all estimations.

Table 3-2 reports the estimation results for emerging market countries. LGNI is negative but insignificant, so that we could not obtain the evidence that equity portfolio investment flow from relatively-rich to relatively-poor emerging market countries. KAOPEN has a negative sign in all equations and significant in five out of eight regressions. The coefficients of DC are only significant at 10% significant level in regressions excluding exchange rate volatility.

Characteristic result in Table 3-2 is about stock market development. SMC is negative and significant in five out of eight regressions. Although the interpretation of this result is controversial, one possible explanation is that the countries with well-developed stock market have high availability and familiarity of securities investment, so that these countries actively increase in equity portfolio investment for other countries.

When we evaluate the results in Table 3-1 and Table 3-2 overall, several interesting properties of equity portfolio investment are revealed. First, there is a threshold of domestic credit market development attracting portfolio investment inflows. The domestic credit market development is positive and significant at 5% significant in almost all estimations in OECD but significant only half of all equations in emerging market. As seen in Table 1, OECD countries have well-developed financial market compared to emerging market countries. This result suggests that there exists a threshold of financial development below which asymmetric information problems prevent equity portfolio investment flow and foreign investors require more sophisticated domestic credit market to mitigate these problems.

Second, in OECD countries, the financial market integration has no effect on equity portfolio investment, whereas in emerging market countries, it induces the outflow of equity portfolio investment. KAOPEN is positive and insignificant in Table3-1, but has negative and significant in Table3-2.

4.4.

Discussion

The above results provide some indications as to what determines the composition of capital

14

flows. The most interesting result is that the domestic credit market development has a different threshold effect on equity-related capital flows. As for FDI, the domestic credit market development has a positive effect solely on emerging market countries (Table 2-2), but not as for equity portfolio investment (Table 3-2). It has rather positive impact on equity portfolio investment in OECD countries (Table 3-1). These results mean that the domestic credit market development affect capital flows by type in different ways depending on the degree of its development. As financial market develops beyond some threshold, countries can induce FDI inflow. If financial market development exceeds a certain threshold, in turn equity portfolio investment begins to flow in.

FDI and equity portfolio investments have been distinguished in the degree of the share of stock acquisition. This substantially means that both investments have been discriminated the degree of separation of ownership from management. According to the asymmetric information problem aspects, information disparity between managers and owners (foreign investors) in FDI is narrower than equity portfolio investment because in FDI foreign investors directly implicate the management of invested corporation. From the standpoint of this aspect, foreign investors may require more sophisticated domestic credit market to mitigate these problems if they invest in equity portfolio investment. These results are consistent with this aspect.

Market liberalization policies have different effect on net capital flows depending on the types of capital flows. Opening up the financial market induce FDI inflows but have opposite effect on equity portfolio investment flow in emerging market countries (Table 2-2, Table 3-2), so that market liberalization policies may change the composition of capita flows, reducing the share of portfolio investment in total flows and increasing the share of FDI flows.

Moreover, adverse effect of financial market integration has been observed depending on the level of financial development. Although, in OECD countries, financial market liberalization doesn’t induce equity portfolio investment outflows (Table2-2, Table3-2), it provokes these outflows in emerging market counties. As Sakuragawa and Hamada (2001) pointed out, capital account liberalization cause capital flight from a country which has underdeveloped financial infrastructures such as ill-organized legal and opaque accounting system, so that capital account liberalization should be carried out as a part of fundamental financial reform complemented by prudential regulation and supervision and financial infrastructure improvement.

5.

Conclusion

Our objective in this paper has been to analyze empirically the determinants of FDI and equity portfolio investments, and indicate the direction for sound economic management in the age of globalization. In this paper, we have focused on four determinants, considered as

15

common factors to impact on each type of international capital flows. We find broad evidences that market liberalization policies have different effect on net capital flows depending on the types of capital flows and the level of economic development. Specifically, we find that financial market integration does appear to alter the composition of capital flows in the direction of reducing the share of equity portfolio investment flows while increasing that of FDI. This finding partly explains the change of the composition of capital flows after Asian crisis.

Our paper is also related to the work on the role of financial development on economic growth. It is shown in this paper that financial development is one of important determinants of equity-related capital inflows and affects capital flows by type in different ways depending on the degree of its development. As financial market develops beyond some threshold, countries can induce FDI inflow. If financial market development exceeds a certain threshold, in turn equity portfolio investment begins to flow in. Reisen and Soto (2001) showed that FDI and equity portfolio investments exert a positive significant effect on income growth, but bonds and official flows, by contrast, do not produce any significant impact on growth in developing countries. Our finding suggests that the financial development contribute to the economic growth by attracting capital flows by type in different ways according to the degree of development.

These results indicate the direction for sound economic management in the age of globalization; a country with insufficient domestic financial market development should be a prudent with lifting capital control and promote the consolidation of the various financial infrastructures to attract FDI and spur economic growth; then, after the degree of financial market development exceed a certain threshold, a country with sophisticated domestic financial market development should lift capital control in a positive manner to attract equity portfolio investment and fuel economic growth.

16

References

Albuquerque, R.,(2003), “The composition o9f international capital flows: risk sharing through foreign direct investment”. Journal of International Economics 61, 353-383.

Alfaro, L., Chanda, A., Kalemli-Ozcan, S., Sayek, S.(2004) “FDI and economic growth: the role of local financial markets,” Journal of International Economics 64, pp.89-112.

Alfaro, L., Chanda, A., Kalemli-Ozcan, S., Volosovych, V. (2008) “Why doesn’t Capital Flow from Rich to Poor Countries? An Empirical Investigation,” Review of Economics and

Statistics 90(2), pp.347-368.

Arellano, M., and Bond, S. (1991) “Some Tests of Specification for Panel Data: Monte Carlo

Evidence and an Application to Employment Equations,” Review of Economic Studies 58, pp.277-297.

Barro, R.J., Lee, J.W.(2000) “International Data on Educational Attainment Update and

Implications,” Center for International Development Working Paper No.042.

Beck, T., Demirguc-Kunt, A., Levine, R.(2000) “A new database on the structure and development of the financial sector,” Policy Research Paper vol.2147. World Bank,

Washington, DC.

Blonigen B.A.(2005) “A Review of the empirical literature on FDI determinants,” NBER

Working Paper No.11299.

Blundell, R., and Bond, S.(1998) “Initial conditions and moment restrictions in dynamic panel data models,” Journal of Econometrics 87, pp.115-143.

Boyd, J.H. and B.D. Smith.(1997) “Capital Market Imperfections, International Credit Markets, and Nonconvergence,” Journal of Economic Theory , 73, pp.335-364.

Calvo, G., Leiderman, L., Reinhart, C.(1993) “Capital Inflows and The Real Exchange Rate

Appreciation in Latin America: The Role of External Factors”, IMF Staff Papers, 40(1)

Chinn, M.D., Ito, H.(2006) “What matters for financial development? Capital controls, institutions, and interactions,” Journal of Development Economics 81, pp.163-192.

Chinn, M.D., Ito, H.(2002) “Capital account liberalization, institutions and financial development: cross country evidence,” NBER Working Paper No.8967.

Chinn, M.D., Ito, H.(2008) “A New Measure of Financial Openness,” Journal of Comparative

Policy Analysis 10(3), pp.309-322.

Chuhan, P., Claessens, S., Mamingi, N.(1998) “Equity and bond flows to Latin America and

Asia: the role of global and country factors,” Journal of Development Economics , 55, pp.439-463.

Coughilin, Cletus and Eran Segev.(2000) “Foreign Direct Investment in China: A Spatial

Econometric Study,” The World Economy, 23(1), pp.1-23

Durham, J.B.(2004) “Absorptive capacity and the effects of foreign direct investment and equity foreign direct investment and equity foreign portfolio investment on economic growth,”

European Economic Review 48, pp.285-306.

Faisal, A., Rabah, A. and Norbert, F. (2005) “The Composition of Capital Flows: Is South Africa

17

Different?” IMF Working Paper WP/05/40.

Froot, K.A., and Stein, J.C. (1991) “Exchange Rates and Foreign Direct Investment: An

Imperfect Capital Markets Approach,” Quarterly Journal of Economics , 106(4), pp.1191-1217.

Gertler, M. and K. Rogoff(1990) “North-South Lending and Endogenous Domestic Capital

Market Inefficiencies,” Journal of Monetary Economics , 26, pp.245-266.

La Porta, R., Lopez-de-Silanes, F., Shleifer, A., Vishny, R.W. (1997) “Legal determinants of external finance,” Journal of Finance , 52, pp.1131-1150.

La Porta, R., Lopez-de-Silanes, F., Shleifer, A., Vishny, R.W. (1998) “Law and Finance,”

Journal of Political Economy , 106, pp.1133-1155.

Levine, R.(1998) “Stock markets, banks, and economic growth,” American Economic Review

88, pp.537-558.

Levine, R.(2002) “Bank-based or market-based financial systems: which is better?,” Journal of

Financial Intermediation, 11, pp.398-428.

Levine, R., Loayza, N., Beck, T.(2000) “Financial intermediation and growth: causality and causes,” Journal of Monetary Economics, 46, pp.31-37.

Li, X., Liu, X.(2005) “Foreign Direct Investment and Economic Growth: An Increasingly

Endogenous Relationship,” World Development 33(3), pp.393-407.

Lucas, R.E.(1990) “Why Doesn’t Capital Flow from Rich to Poor Countries?, ” The American

Economic Review 80(2), pp.92-96.

Matsuyama, K.(2004) “Financial Market Globalization, Symmetry-Breaking and Endogenous

Inequality of Nations, ” Econometrica , 72, pp.853-884.

Montiel, Peter and Carmen M. Reinhart.(1999) “Do Capital Controls and Macroeconomic

Policies Influence the Volume and Composition of Capital Flows? Evidence from the

1990s,” Journal of International Money and Finance , 18, pp. 619-635.

Prasad, E.S., Rajan, R.G., Subramanian, A.(2007) “Foreign Capital and Economic Growth,”

NBER Working Paper No.13619.

Rajan, R., Zingales, L.(2003) “The great reversals: the politics of financial development in the twentieth century,” Journal of Finance 69

Reisen, H. and Soto, M.(2001) “Which Types of Capital Inflows Foster Developing-Country

Growth?,” International Finance 4(1), pp.1-14.

Sakuragawa, M. and K. Hamada(2001) “Capital Flight, North-South Lending, and Stages of

Economic Development,” International Economic Review , 42, pp.1-24.

Schnitzer, M.(2002) “Debt vs. Foreign Direct Investment: The Impact of Sovereign Risk on the

Structure of International Capital Flows,” Economica 69, pp.41-67.

Windmeijer, F.(2005) “A finite sample correction for the variance of linear efficient two-step

GMM estimators,” Journal of Econometrics 126, pp.25-51.

18

19

Figure 1. Net Financial Account of Nominal GDP in the World

1.80%

1.60%

1.40%

1.20%

1.00%

0.80%

0.60%

0.40%

0.20%

0.00%

-0.20%

1985 1986 1987 1988 1989 1990 1991 1992 1993 1994 1995 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005

Source: IMF, International Financial Statistics

20

Figure 2. Net FDI Flows to OECD and Emerging Market Countries

3.50%

3.00%

2.50%

2.00%

1.50%

1.00%

0.50%

0.00%

-0.50%

OECD countries

Emerging market countries

-1.00%

-1.50%

1985 1986 1987 1988 1989 1990 1991 1992 1993 1994 1995 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005

Source: IMF, International Financial Statistics

21

3.00%

2.00%

1.00%

0.00%

-1.00%

-2.00%

Figure 3. Net Portfolio Investment Flows to OECD and Emerging Market Countries

OECD countries

Emerging market countries

-3.00%

1985 1986 1987 1988 1989 1990 1991 1992 1993 1994 1995 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005

Source: IMF, International Financial Statistics

22

0.60%

0.40%

0.20%

0.00%

-0.20%

-0.40%

-0.60%

-0.80%

Figure 4. Net Equity Portfolio Investment Flows to OECD and Emerging Market Countries

OECD countries

Emerging market countries

-1.00%

1985 1986 1987 1988 1989 1990 1991 1992 1993 1994 1995 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005

Source: IMF, International Financial Statistics

23

3.00%

Figure 5. Net Debt Portfolio Investment Flows to OECD and Emerging Market Countries

OECD countries

Emerging market countries

2.50%

2.00%

1.50%

1.00%

0.50%

0.00%

-0.50%

-1.00%

-1.50%

1985 1986 1987 1988 1989 1990 1991 1992 1993 1994 1995 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005

Source: IMF, International Financial Statistics

24

Sample

Foreign Direct Investment (FDI)

Equity Portfolio Investment

Log of GNI per capita (LGNI)

Human Capital (HC)

Exchange Rate Volatility (ERV)

Goods Market Openness (GOPEN)

Financial Market Openness (KAOPEN)

Domestic Credit to private sector (DC)

Stock Market Capitalization (SMC)

Sample

Foreign Direct Investment (FDI)

Equity Portfolio Investment

Log of GNI per capita (LGNI)

Human Capital (HC)

Exchange Rate Volatility (ERV)

Goods Market Openness (GOPEN)

Financial Market Openness (KAOPEN)

Domestic Credit to private sector (DC)

Stock Market Capitalization (SMC)

Table 1. Descriptive Statistics

OECD Countries

1300

357

1510

1553

776

1448

1576

1466

699

515

401

537

546

500

545

511

511

421

0.0005

-0.0039

9.6915

2.1849

0.0143

0.6631

1.6528

0.8299

0.5824

0.0234

0.0236

0.7234

0.2096

0.0162

0.3157

1.2123

0.4244

0.4668

Emerging market Countries

0.1069

0.1124

11.0399

2.5360

0.2602

2.0186

2.5398

2.0551

2.6718

-0.0993

-0.1309

7.4900

1.3470

0.0020

0.1655

-1.7975

0.1111

0.0019

0.0160

-0.0047

6.9628

1.3708

0.0349

0.7635

-0.1285

0.3639

0.3690

0.0227

0.0238

1.2772

0.6103

0.1108

0.5619

1.4798

0.3530

0.4585

0.1238

0.0596

10.3650

2.2757

2.7923

4.4365

2.5398

2.1374

2.6718

-0.0713

-0.1413

4.4998

-0.7052

0.0024

0.0666

-1.7975

0.0149

0.0028

25

Estimation Method

Table 2-1. Determinants of Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) in OECD Countries

OLS

(i)

OLS

(ii)

OLS

(iii)

OLS

(iv)

SGMM

(v)

SGMM

(vi)

0.3619

[6.91] ***

0.3622

[6.90] ***

0.3471

[6.41] ***

0.3474

[6.40] ***

0.2609

[1.67] *

0.2727

[1.82] *

Lagged Dependent

Log of GNI per capita(LGNI)

Human Capital(HC)

-0.0096

[-2.99] ***

0.0081

[1.24]

-0.0096

[-2.97]

0.0080

[1.23]

Exchange Rate Volatility(ERV)

Goods Market Openness(GOPEN) 0.0071

[1.70] *

0.0072

[1.71] *

Financial Market Openness(KAOPEN) 0.0000

[0.02]

0.0000

[1.67] *

Domestic Credit to private sector(DC) -0.0006

[-0.16]

-0.0007

[-0.18]

Stock Market Capitalization(SMC) -0.0084

[-2.94] ***

-0.0084

[-2.92] ***

Asian-Crisis Dummy -0.0006

[-0.23]

Constant

Arellano-Bond test (AR2)

Hansen test

Adjusted R-sq

Number of observation

Number of countries

0.0776

[3.17]

0.4233

358

26

***

0.0774

[3.15]

0.4217

358

Notes: a) The dependent variable is net foreign direct investment over GDP

26

*** b) * significant at 10%;** significant at 5%; *** significant at 1%.

***

-0.0108

[-3.13]

0.0076

[1.11]

-0.0020

[-0.01]

0.0071

[1.69] *

-0.0003

[-0.18]

-0.0017

[-0.45]

-0.0077

[-2.64]

0.0924

[3.42]

0.4303

347

26

***

***

***

-0.0108

[-3.11] ***

0.0075

[1.10]

-0.0045

[-0.03]

0.0072

[0.20]

-0.0002

[-0.16]

-0.0020

[-0.50]

-0.0077

[-2.61]

-0.0012

[-0.40]

0.0923

[3.41]

0.4289

347

26

***

***

-0.0100

[-0.91]

0.0154

[1.53]

0.0071

[1.29]

0.0000

[-0.02]

-0.0017

[-0.32]

-0.0116

[-2.67]

0.0687

[0.83]

0.718

1.000

c) The value in parentheses in the “OLS” column is t-statistics which is calculated based on the White’s robust standard errors.

358

26

***

-0.0113

[-0.82]

0.0154

[1.43]

0.0072

[1.22]

0.0001

[0.03]

-0.0010

[-0.15]

-0.0111

[-0.21]

0.0809

[0.77]

0.69

1.000

[-2.65] ***

-0.0004

358

26 d) The value in parentheses in the “SGMM” column is z-statistics which is calculated based on two-step standard errors, with the Windmeijer’s correction. e) “Arellano-Bond test” is the p-value of autocorrelation test for residual in differences. “Hansen test” is the p-value of overidentifying restrictions test. f) “Hansen test” is the p-value of overidentifying restrictions test.

SGMM

(vii)

0.1796

[0.70]

-0.0099

[-0.87]

0.0141

[1.54]

0.1101

[0.39]

0.0095

[0.83]

-0.0005

[-0.24]

-0.0029

[-0.49]

-0.0123

[-2.20] **

0.0711

[0.79]

0.998

1.000

347

26

SGMM

(viii)

0.1129

[0.43]

-0.0110

[-0.89]

0.0156

[1.72] *

0.1040

[0.47]

0.0113

[1.10]

-0.0004

[-0.16]

-0.0035

[-0.56]

-0.0139

[-2.32] **

-0.0005

[-0.31]

0.0786

[0.81]

0.876

1.000

347

26

26

Estimation Method

Lagged Dependent

Log of GNI per capita(LGNI)

Human Capital(HC)

Table 2-2. Determinants of Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) in Emerging Market Countries

OLS

(i)

OLS

(ii)

OLS

(iii)

OLS

(iv)

SGMM

(v)

SGMM

(vi)

0.4352

[11.28] ***

0.4197

[10.93] ***

0.5259

[10.97] ***

0.5198

[10.84] ***

0.3739

[3.31] ***

0.3750

[2.68] ***

-0.0034

[-2.29] **

-0.0020

[-1.24]

-0.0025

[-1.16]

-0.0016

[-0.68]

-0.0017

[-0.53]

-0.0024

[-0.64]

0.0019

[0.47]

0.0007

[0.16]

-0.0051

[-0.93]

-0.0088

[-1.39]

0.0064

[0.72]

0.0071

[0.93]

-0.0841

[-2.05] **

-0.0693

[-1.63]

Exchange Rate Volatility(ERV)

Goods Market Openness(GOPEN) 0.0048

[1.78] *

0.0073

[2.63] ***

Financial Market Openness(KAOPEN) 0.0028

[4.22] ***

0.0029

[4.42] ***

Domestic Credit to private sector(DC) 0.0086

[2.30] **

0.0088

[2.32] **

Stock Market Capitalization(SMC) -0.0008

[-0.26]

-0.0010

[-0.33]

Asian-Crisis Dummy

0.0064

[2.73] ***

Oil-Country Dummy

-0.0035

[-1.31]

Harmful-Tax-Country Dummy

Constant

Arellano-Bond test (AR2)

Hansen test

Adjusted R-sq

Number of observation

Number of countries

0.0262

[2.97]

0.3886

599

49

***

-0.0113

[-2.72] ***

0.0169

[1.81]

0.4037

599

Notes: a) The dependent variable is net foreign direct investment over GDP b) * significant at 10%;** significant at 5%; *** significant at 1%.

49

*

-0.0035

[-0.84]

0.0017

[2.12] **

0.0103

[2.28]

0.0031

[0.87]

0.0375

[2.78]

0.5654

356

31

**

***

-0.0005

[-0.12]

0.0021

[2.54] **

0.0074

[1.52]

0.0042

[1.13]

0.0038

[1.53]

-0.0027

[-0.82]

-0.0096

[-1.20]

0.0367

[2.69]

0.5679

356

31

***

0.0007

[0.25]

0.0032

[3.65] ***

0.0091

[2.55]

-0.0038

[-1.12]

0.0101

[0.75]

0.135

1.000

599

49

**

0.0023

[0.82]

0.0036

[4.06] ***

0.0108

[2.39]

-0.0030

[-0.78]

-0.0005

[-1.55]

0.0133

[0.73]

0.13

1.000

599

49

**

0.0039

[2.24] **

-0.0005

[-1.44] c) The value in parentheses in the “OLS” column is t-statistics which is calculated based on the White’s robust standard errors. d) The value in parentheses in the “SGMM” column is z-statistics which is calculated based on two-step standard errors, with the Windmeijer’s correction. e) “Arellano-Bond test” is the p-value of autocorrelation test for residual in differences. “Hansen test” is the p-value of overidentifying restrictions test. f) “Hansen test” is the p-value of overidentifying restrictions test.

SGMM

(vii)

0.5966

[5.07] ***

-0.0001

[-0.01]

-0.0006

[-0.03]

-0.0713

[-1.10]

0.0002

[0.06]

0.0021

[1.85] *

0.0064

[1.52]

-0.0020

[-0.48]

0.0100

[0.28]

0.497

1.000

356

31

27

SGMM

(viii)

0.5879

[3.91] ***

0.0007

[0.05]

-0.0068

[-0.22]

-0.0579

[-0.42]

0.0004

[0.10]

0.0023

[1.58]

0.0071

[1.85] *

-0.0018

[-0.34]

0.0022

[0.90]

-0.0004

[-1.67] *

-0.0002

[-0.24]

0.0154

[0.30]

0.443

1.000

356

31

Estimation Method

Lagged Dependent

Log of GNI per capita(LGNI)

Human Capital(HC)

Table 3-1. Determinants of Equity Foreign Portfolio Investment in OECD Countries

OLS

(i)

OLS

(ii)

OLS

(iii)

OLS

(iv)

SGMM

(v)

SGMM

(vi)

0.1691

[2.75] ***

0.1666

[2.70] ***

0.1744

[2.77] ***

0.1720

[2.73] ***

0.1962

[0.79]

0.1866

[0.78]

-0.0169

[-3.76] ***

-0.0171

[-3.80] ***

-0.0169

[-3.62] ***

-0.0171

[-3.65] ***

-0.0258

[-2.33] **

-0.0276

[-2.63] ***

-0.0054

[-0.54]

-0.0051

[-0.51]

-0.0059

[-0.57]

-0.0058

[-0.55]

-0.0045

[-0.61]

-0.0043

[-0.53]

0.1071

[0.55]

0.1135

[0.59]

Exchange Rate Volatility(ERV)

Goods Market Openness(GOPEN) -0.0109

[-1.76] *

-0.0110

[-1.78] *

Financial Market Openness(KAOPEN) 0.0001

[0.01]

0.0000

[-1.65] *

Domestic Credit to private sector(DC) 0.0141

[2.53] **

0.0146

[2.60] ***

Stock Market Capitalization(SMC) -0.0023

[-0.70]

-0.0024

[-0.72]

Asian-Crisis Dummy

0.0033

[0.79]

Constant

Arellano-Bond test (AR2)

Hansen test

Adjusted R-sq

Number of observation

Number of countries

0.1707

[4.62]

0.1366

311

24

***

0.1719

[4.64]

0.1355

311

24

***

Notes: a) The dependent variable is net equity foreign portfolio investment over GDP

-0.0104

[-1.67] *

0.0004

[0.19]

0.0137

[2.41]

-0.0024

[-0.71]

0.1331

306

24

**

0.1697

[4.44] ***

-0.0105

[-0.42]

0.0003

[0.16]

0.0142

[2.48]

-0.0024

[-0.73]

**

0.0033

[0.79]

0.1705

[4.46] ***

0.132

306

24

-0.0105

[-1.71] *

0.0032

[1.20]

0.0186

[2.03]

-0.0028

[-0.81]

**

0.2467

[2.60] ***

0.311

1.000

311

24

-0.0108

[-1.67] *

0.0038

[1.37]

0.0191

[2.11]

-0.0026

[-0.73]

0.2613

[2.97] ***

0.302

1.000

311

24

**

0.0027

[0.95] b) * significant at 10%;** significant at 5%; *** significant at 1%. c) The value in parentheses in the “OLS” column is t-statistics which is calculated based on the White’s robust standard errors. d) The value in parentheses in the “SGMM” column is z-statistics which is calculated based on two-step standard errors, with the Windmeijer’s correction. e) “Arellano-Bond test” is the p-value of autocorrelation test for residual in differences. “Hansen test” is the p-value of overidentifying restrictions test. f) “Hansen test” is the p-value of overidentifying restrictions test.

SGMM

(vii)

0.1939

[0.73]

-0.0250

[-2.16] **

-0.0049

[-0.47]

0.0960

[0.48]

-0.0099

[-1.68] *

0.0033

[1.02]

0.0172

[2.00] **

-0.0028

[-0.75]

0.2387

[2.61] ***

0.336

1.000

306

24

SGMM

(viii)

0.1927

[0.71]

-0.0270

[-2.50] **

-0.0033

[-0.30]

0.1012

[0.50]

-0.0104

[-1.66] *

0.0038

[1.18]

0.0173

[1.96] *

-0.0026

[-0.75]

0.0030

[1.03]

0.2535

[3.11] ***

0.330

1.000

306

24

28

Estimation Method

Lagged Dependent

Log of GNI per capita(LGNI)

Human Capital(HC)

Table 3-2. Determinants of Equity Foreign Portfolio Investment in Emerging Market Countries

OLS

(i)

OLS

(ii)

OLS

(iii)

OLS

(iv)

SGMM

(v)

SGMM

(vi)

0.5224

[8.34] ***

0.5171

[8.15] ***

0.4911

[6.75] ***

0.4569

[5.88] ***

0.5048

[7.00] ***

0.5055

[6.71]

-0.0028

[-1.21]

-0.0025

[-1.08]

-0.0047

[-0.96]

-0.0058

[-1.13]

-0.0040

[-1.53]

-0.0040

[-1.33]

0.0073

[0.93]

0.0085

[1.04]

0.0070

[0.61]

0.0033

[0.26]

0.0077

[1.33]

0.0080

[1.47]

0.0892

[1.02]

0.0641

[0.71]

Exchange Rate Volatility(ERV)

Goods Market Openness(GOPEN) -0.0054

[-1.72] *

-0.0055

[-1.72] *

Financial Market Openness(KAOPEN) -0.0022

[-2.09] **

-0.0022

[-2.08] **

Domestic Credit to private sector(DC) 0.0124

[1.65] *

0.0127

[1.68] *

Stock Market Capitalization(SMC) -0.0095

[-2.03] **

-0.0096

[-2.06] **

Asian-Crisis Dummy

-0.0019

[-0.49]

Oil-Country Dummy

0.0032

[0.68]

Harmful-Tax-Country Dummy

Constant

Arellano-Bond test (AR2)

Hansen test

Adjusted R-sq

Number of observation

Number of countries

0.0109

[0.66]

0.5524

215

28

-0.0039

[-0.43]

0.0072

[0.41]

0.5474

215

28

Notes: a) The dependent variable is net equity foreign portfolio investment over GDP b) * significant at 10%;** significant at 5%; *** significant at 1%.

-0.0050

[-0.80]

-0.0017

[-1.21]

0.0114

[1.17]

-0.0112

[-1.79]

0.0260

[0.64]

0.593

147

17

*

-0.0055

[-0.85]

-0.0014

[-0.94]

0.0098

[0.98]

-0.0091

[-1.40]

-0.0012

[-0.24]

0.0051

[0.89]

-0.0229

[-1.21]

0.0436

[0.92]

0.5893

147

17

-0.0051

[-4.34] ***

-0.0020

[-4.47] ***

0.0077

[1.82]

-0.0065

[-1.99]

0.0210

[1.36]

0.279

1.000

215

28

*

**

0.0080

[1.84]

-0.0064

[-2.06]

0.0201

[1.18]

0.269

1.000

215

28

***

-0.0051

[-3.27] ***

-0.0020

[-4.26] ***

*

**

-0.0007

[-0.45]

0.0001

[1.06] c) The value in parentheses in the “OLS” column is t-statistics which is calculated based on the White’s robust standard errors. d) The value in parentheses in the “SGMM” column is z-statistics which is calculated based on two-step standard errors, with the Windmeijer’s correction. e) “Arellano-Bond test” is the p-value of autocorrelation test for residual in differences. “Hansen test” is the p-value of overidentifying restrictions test. f) “Hansen test” is the p-value of overidentifying restrictions test.

29

SGMM

(vii)

0.5218

[1.84]

-0.0189

[-1.19]

0.0378

[1.09]

-0.1500

[-0.69]

0.0012

[0.10]

*

-0.0026

[-2.53] **

0.0125

[0.79]

-0.0096

[-0.43]

0.0861

[1.06]

0.49

1.000

147

17

SGMM

(viii)

0.5646

[1.39]

0.0363

[0.82]

-0.0427

[-0.63]

0.3549

[1.12]

-0.0208

[-0.95]

-0.0021

[-1.19]

0.0069

[0.59]

-0.0057

[-0.93]

-0.0006

[-0.18]

0.0005

[0.92]

-0.2188

[-0.96]

0.28

1.000

147

17

Africa Asia

Table 4. Countries in the Sample

Europe South and North America Other

Botswana China Belgium Bolivia Barbados

Egypt, Arab Rep. Hong Kong, China Cyprus Brazil Fiji

Jordan

Kenya

Kuwait

Uganda

Iran, Islamic Rep.

Japan

Korea, Rep.

Swaziland Nepal

Sri Lanka

France

Germany

Greece

Ireland

Colombia

Costa Rica

El Salvador

Panama

Papua New Guinea

Trinidad and Tobago

Mauritius Lebanon Hungary Guatemala

South Africa Malaysia Iceland Mexico

Tanzania Pakistan Italy Paraguay

Netherlands

Norway United States

Zimbabwe Turkey Portugal Venezuela,

Spain

Sweden

Switzerland

!

!

!

!

Number of countries:

16 16 20 16 7 75

30

Table 5. Variables and Sources

Variable Definition Source

Net Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) Net Foreign Direct Investment over GDP

Net Foreign Portfolio Investment (FPI) Net Foreign Portfolio Investment over GDP

Net Equity Foreign Portfolio Investment (EFPI) Net Equity Foreign Portfolio Investment over GDP

Net Debt Foreign Portfolio Investment (DFPI) Net Debt Foreign Portfolio Investment over GDP

Log of GNI per capita (LGNI) Log of GNI per capita, Atlas method (current US$)

Human Capital (HC) Log of Average schooling years in the total population

Goods Market Openness (GOPEN)

Financial Market Openness (KAOPEN)

(Exports plus Imports) over GDP

Chinn-Ito Financial openness index

Domestic credit to private sector (DC)

Stock Market Capitalization (SMC)

Stock Market Total Value Traded (STV)

Asian-Crisis Dummy

Oil-Country Dummy

Harmful-Tax-Country Dummy

IMF, International Financial Statistics

IMF, International Financial Statistics

IMF, International Financial Statistics

IMF, International Financial Statistics

World Bank, WDI online

Barro and Lee(2000)

IMF, International Financial Statistics

Chinn and Ito(2008)

Domestic credit to private sector in the beginning of period over GDP World Bank, WDI online

Market capitalization of listed companies in the beginning of period over GDP World Bank, WDI online

Stocks traded, total value over GDP

Dummy variable if year equals 1997 or 1998

Dummy variable if country is a oil producer

Dummy variable if country has a harmful tax practice

World Bank, WDI online

-

-

-

31