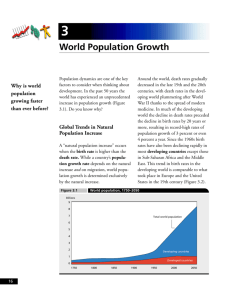

Full Report - Population Reference Bureau

advertisement