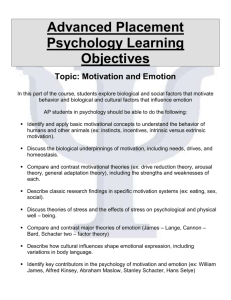

Emotional Intelligence: An Integrative Meta

advertisement