Report of the Ad Hoc Committee on the Uniform Bar Examination

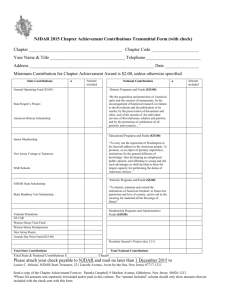

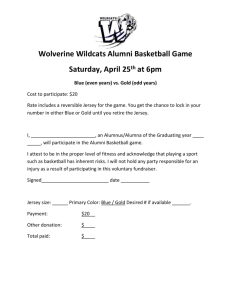

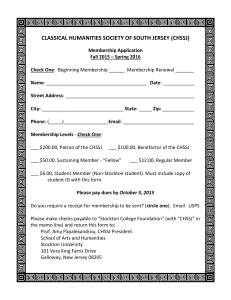

advertisement